One minute to midnight: Kennedy, Khrushchev, and Castro on the brink of nuclear war (16 page)

Read One minute to midnight: Kennedy, Khrushchev, and Castro on the brink of nuclear war Online

Authors: Michael Dobbs

Previously unpublished photograph of a U.S. Navy RF-8 Crusader flying over central Cuba on Thursday, October 25, on Blue Moon Mission 5010.

[NARA]

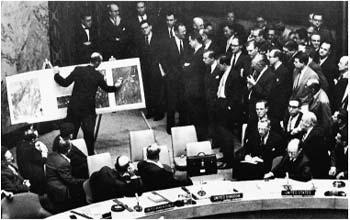

Adlai Stevenson at the United Nations during the Security Council debate on October 25, using photos of Soviet missile sites.

[UN]

Previously unpublished Air Force photographs of the SAM site at San Julian in western Cuba showing radar and fire control vans in the center surrounded by entrenched and camouflaged missile positions.

[NARA]

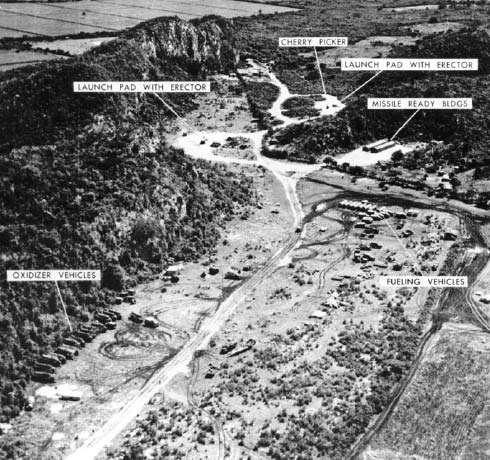

The first photograph, taken by a U-2 piloted by Major Richard Heyser on October 14, that convinced President Kennedy that the Soviet Union had deployed medium-range missiles to Cuba. It shows San Cristobal MRBM Site No. 1, the same site photographed by Commander Ecker on October 23.

[NARA]

Colonel Ivan Sidorov, commander of a medium-range R-12 missile regiment stationed near Sagua la Grande.

[MAVI]

Sagua la Grande MRBM Site No. 2, photographed October 23.

[NARA]

There was a realistic side to Castro's romanticism. Under siege at home, he calculated correctly that most Cubans still supported him on the issue of national independence, whatever their economic or political grievances. He was confident that he could deal with more mini-invasions by Cuban exiles or even a guerrilla uprising supported by Washington. But he also knew he could not defeat an all-out U.S. invasion. "Direct imperialist aggression," he told his supporters in July 1962, on the ninth anniversary of Moncada, represented the "final danger" for the Cuban revolution.

The only effective way of dealing with this danger was a military alliance with the other superpower. When Khrushchev first broached the idea of sending missiles to Cuba back in May 1962, his Cuba specialists had been skeptical that Castro would agree. They reasoned that he would not do anything that might undermine his popular standing in the rest of Latin America. In fact, Fidel quickly accepted the Soviet offer, insisting only that his agreement be seen as "an act of solidarity" by Cuba with the Socialist bloc rather than an act of desperation. The preservation of national dignity was all-important.

Castro would have preferred a public announcement about the missile deployment, but reluctantly went along with Khrushchev's insistence on secrecy, until all the missiles were in place. At first, knowledge of the deployments was limited to Castro and four of his closest aides; but the circle of those in the know gradually widened. The garrulous Cubans, Castro included, were bursting to tell the rest of the world about the missiles. On September 9, the very same day that the Soviet freighter

Omsk

docked in the port of Casilda with six R-12 missiles, a CIA informant overheard Castro's private pilot claiming that Cuba possessed "many mobile ramps for intermediate-range rockets.... They don't know what's awaiting them." Three days later, on September 12,

Revolucion

devoted its entire front page to a menacing headline in jumbo-sized type:

ROCKETS WILL BLAST THE UNITED STATES IF THEY INVADE CUBA.

Cuban president Osvaldo Dorticos almost gave the game away at the United Nations on October 8 when he boasted that Cuba now possessed "weapons that we wish we did not need and that we do not want to use" and that a

yanqui

attack would result in "a new world war." He was greeted on his return by an effusive Fidel, who also hinted at the existence of some formidable new means of retaliation against the United States. The Americans might be able to begin an invasion of Cuba, he conceded, "but they would not be able to end it." In private, a senior Cuban official told a visiting British reporter in mid-October that there were now "missiles on Cuban territory whose range is good enough to hit the United States and not only Florida." Furthermore, the missiles were "manned by Russians."

In retrospect, of course, it is remarkable that the U.S. intelligence community did not pick up on all these hints and conclude much earlier that there was a strong likelihood that the Soviet Union had deployed nuclear missiles to Cuba. At the time, however, CIA analysts dismissed the boasts as typical Cuban braggadocio.

While Castro was haranguing the people of Cuba, Che Guevara was preparing to spend his second night in the Sierra del Rosario. He had arrived at his mountain hideout the previous evening with a convoy of jeeps and trucks, and had spent the day organizing defenses with local military chiefs. If the Americans invaded, he planned to transform the hills and valleys of western Cuba into a bloody death trap, like "the pass at Thermopylae," in Castro's phrase.

An elite force of two hundred fighters, many of them old companions from the revolutionary war, had accompanied Che into the mountains. For his military headquarters, the legendary guerrilla leader had chosen a labyrinthine system of caves hidden among mahogany and eucalyptus trees. Carved out of the soft limestone by rushing streams, la Cueva de los Portales resembled a Gothic cathedral, with an arched nave surrounded by a warren of chambers and passageways. Soviet liaison officers were busy installing a communications system, including wireless and a hand-powered landline. Cuban soldiers were doing their best to make the damp and humid cave inhabitable.

Situated midway between the north and south coasts of Cuba, near the source of the San Diego River, la Cueva de los Portales occupied a strategic mountain pass. Had he followed the river southward for ten miles, Che would have arrived at one of the Soviet missile sites. Looking northward, he faced the United States. He knew that Soviet troops had stationed dozens of nuclear-tipped cruise missiles on this side of the island. These weapons would serve as Cuba's ultimate line of defense against a

yanqui

invasion.

At the age of thirty-four, the Argentinean-born doctor had spent the past decade wandering around Latin America and waging revolutionary struggle. (He acquired his nickname "Che" from his frequent use of the Argentinean expression for "pal" or "mate.") He had first met Castro in Mexico City on a cold night in 1955, and had fallen immediately under his spell, describing him in his diary as "an extraordinary man...intelligent, very sure of himself, and remarkably bold." By dawn, the ever persuasive Castro had convinced his new friend to sail with him to Cuba and start a revolution.

Che was one of the very few people other than his brother Raul whom Fidel trusted completely. He knew that an Argentinean could never aspire to replace him as leader of Cuba. Together, Fidel, Raul, and Che formed Cuba's ruling triumvirate. Everyone else was either suspect or dispensable.

After the triumph of the revolution, Fidel handed day-to-day control of the army to Raul and the economy to Che. As minister for industry, Che had done as much as anyone to ruin the economy through the doctrinaire application of nineteenth-century Marxist ideas. His travels around Latin America had exposed him to the evil ways of companies like United Fruit: he had sworn, in front of a portrait of "our old, much lamented comrade Stalin," to exterminate such "capitalist octopuses" if he ever got the chance. In Che's ideal world, there was no place for the profit motive or any kind of monetary relations in the economy.

Che's saving grace was his restless idealism. Of all the Cuban leaders, it was he who best encapsulated the contradictions of the revolution, rigidity and romanticism, fanaticism and fraternal feeling. He was a disciplinarian, but also a dreamer. There was a large element of paternalism in his attachment to Marxist ideology: he was convinced that he and other intellectuals knew what was best for the people. At the same time, he was also capable of ruthless self-analysis.

The role of guerrilla strategist was much more to Che's liking than that of government bureaucrat. He had been one of the architects of the victory over Batista, capturing a government ammunition train at Santa Clara in one of the decisive battles of the war. During the abortive Bay of Pigs invasion, Castro had sent him to organize the defense of western Cuba, much as he was doing now.

Like Castro, Che believed that military confrontation with the United States was all but inevitable. As a young revolutionary in Guatemala, he had witnessed a CIA-backed coup against the leftist government of Jacobo Arbenz Guzman in 1954. He had drawn several important lessons from that experience. First, Washington would never permit a socialist regime in Latin America. Second, the Arbenz government had made a fatal mistake by granting "too much freedom" to the "agents of imperialism," particularly in the press. Third, Arbenz should have defended himself by creating armed people's militias and taking the fight to the countryside.

On Castro's instructions, Che was now preparing to do precisely that. If the Americans occupied the cities, the Cuban defenders would fight a guerrilla war, with the help of their Soviet allies. They had arms caches everywhere. Castro had reserved half of his army, and most of his best divisions, for the defense of western Cuba, where most of the missile sites were located and the Americans were expected to land. The whole country could be turned into a Stalingrad, but the focal point of the Cuban resistance would be the nuclear missile bases of Pinar del Rio. And Che Guevara would be in the thick of it.