One to the Wolves, On the Trail of a Killer (2 page)

Read One to the Wolves, On the Trail of a Killer Online

Authors: Lois Duncan

Albuquerque Tribune, April 24, 1991

POLICE BLASTED ON ARQUETTE CASE

by Tribune staff

Two defense attorneys say Albuquerque police conducted a “shoddy” investigation into

the shooting death of Kaitlyn Arquette.

The investigation focused on two innocent men and ignored a possible connection to

Vietnamese gang activity, attorneys Joseph Riggs and Michael Davis said.

District Attorney Bob Schwartz said the decision to drop the charges was partially

based on an investigation by Garcia’s attorneys. They discovered that Arquette’s relationship

with a group of Vietnamese under investigation in a multimillion-dollar insurance

scam may have led to her death.

Had the case gone to trial as scheduled next week, Davis said, “We were going to kill

them on the stand.”

He said the scam involved filing insurance claims on accidents with rental cars. A

car rented with Arquette’s credit card was involved in a California accident. After

the accident a deposit of $1,500 appeared in Arquette’s bank account.

Schwartz declined to comment on the quality of the police work.

Albuquerque Journal, June 9, 1992

MOTHER SURE BOOK WILL HELP SOLVE ARQUETTE KILLING

by Colleen Heild

Albuquerque author Lois Duncan paid a visit to her daughter Kaitlyn’s grave this past

September. She brought along a copy of her latest manuscript – the moving chronicle

of a mother’s search for her child’s killer.

It was Duncan’s own story.

“I set it on the grave marker and told her, ‘Happy birthday honey. This is my present

to you. Mother is going to get your killer’ ”…

I titled my book about our daughter’s murder

One to the Wolves.

The title was suggested by our older son, Brett, who compared his sister’s killers

to wolves who invaded our family flock and made off with a lamb.

Now, on Kait’s twenty-first birthday, I stood at her grave with the manuscript box

in my hands.

“This is your present, honey,” I told her. “Mother is going to get your killer.” Even

to my own ears, the statement sounded ludicrous. How was I going to keep that promise?

Although I had written a number of fictional suspense novels, I knew nothing about

how real murder investigations were conducted. I looked down at the grave marker and

whispered aloud the inscription that Kait’s oldest sister, Robin, had chosen for her

epitaph, the heartbreaking lines that Mark Twain had written for his own daughter:

Warm summer sun, shine kindly here.

Warm southern wind, blow softly here.

Green sod above, lie light, lie light.

Good night, dear heart, good night, good night.

It was autumn now, although the season was veiled in Indian summer and the breeze

that caressed my face was as soft and unthreatening as the breeze that had ruffled

Kait’s hair on that sweet summer evening two years before when she left our home,

never to return. I closed my eyes against the slanted rays of the afternoon sun and

concentrated on picturing my daughter as I wanted to remember her — not as she had

looked in the hospital with her head swathed in bandages, but healthy and strong,

radiant with life and vitality, her green eyes sparkling with mischief and dreams

of adventure.

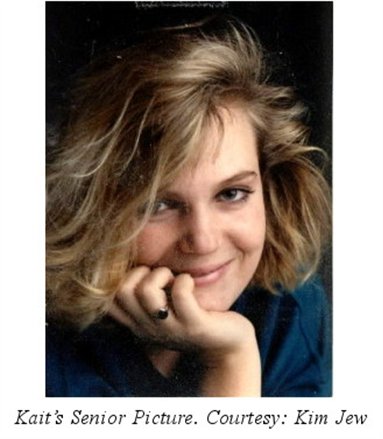

That was how she had looked in her senior picture. She had selected that single picture

out of dozens of poses.

“Are you sure you want to use that one?” I had asked her doubtfully. “It makes you

look like you’re hiding a naughty secret.”

“It’s how I want people to remember me,” Kait had responded.

In retrospect, I thought, what a strange thing to say! Was it possible she had experienced

some sort of premonition? Or was it only that the picture was startlingly glamorous?

I’d enclosed a copy of that photo in the box with the manuscript in case a publisher

wanted to use it on the cover.

When I left the cemetery, I drove to the post office, arriving just before the “closed”

sign went up on the door. It seemed terribly important that Kait’s story be mailed

on her birthday.

By the time I got back to the rented town house where my husband Don and I had been

living since we had been driven out of our family home by threats to the rest of us

following the arrest of three Hispanic suspects, Don had arrived home from work and

was seated at the kitchen table, thumbing through the mail.

“Do you need help bringing in groceries?” he asked me.

“I haven’t been shopping,” I told him. “I’ve come from the post office. I mailed off

the manuscript.”

There was a moment’s silence while Don digested that information.

Then he said, “Don’t you think you’re jumping the gun? Kait’s story doesn’t have an

ending.”

“Getting her story out there where people can read it may be our only chance of

getting

an ending,” I said. “The police have washed their hands of the case, so the book won’t

hurt their investigation. Maybe it will bring informants out of the woodwork.”

“Before that can happen you’ll need to find a publisher,” Don said. “Who’s going to

publish a true crime story that doesn’t end with a conviction?”

When my agent received the manuscript, she had the same reaction.

“I’ve read it,” she told me. “It’s a chilling story, but there isn’t any conclusion.

All those unanswered questions are flapping in the wind. Who was the triggerman? Did

he act on his own or was he hired? Is there a link between the Hispanic suspects and

the Vietnamese group? Did Kait truly have a secret second boyfriend named Rod and,

if so, where is he? What about all those psychic readings about Kait’s having seen

a prominent citizen involved in a drug transaction at a ‘Desert Castle’? How can

we expect anybody to accept

that

?”

“I can’t create an ending when there isn’t one,” I said. “All I can do is describe

events as they occurred. Please, won’t you submit the story anyway?” I didn’t think

I could bear it if she told me she wouldn’t.

“I’ll submit it, but don’t get your hopes up,” my agent told me. “I’ll try your usual

publisher first, since they have a vested interest in your teenage suspense novels.

But I have to warn you that your track record with young people isn’t going to carry

much weight with the adult department.”

Several days later she phoned again.

“It looks like this actually may fly,” she said with obvious surprise. “The editors

are intrigued by the story, but they’re leery of lawsuits. They don’t want to commit

to anything until their legal department gives them a go-ahead.”

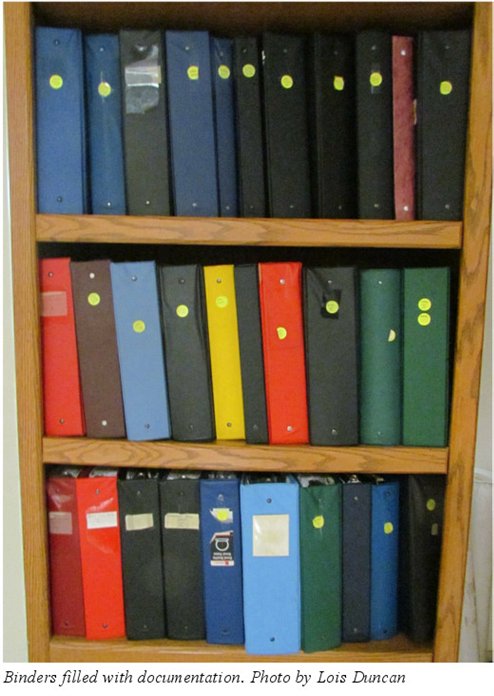

The following week I flew to New York to meet with the publisher’s legal department,

bringing with me suitcases containing the binders of documentation that had filled

an entire bookcase in my home office. Those materials included the APD case file,

transcripts of depositions, a transcript of the grand jury hearing at which Miguel

Garcia and Juve Escobedo were indicted and a scrapbook filled with newspaper clippings

that chronicled the downhill slide of the investigation.

I also brought dozens of audio tapes of phone conversations, since New Mexico was

a state in which it was legal for one party to record phone calls without the second

party’s knowledge.

The publisher’s attorney seemed particularly concerned about a police artist’s sketches,

based upon descriptions of two faces that psychic detective Noreen Renier described

in a trance.

“Has anyone been able to identify those faces?” she asked me.

“The first sketch isn’t of an actual person,” I told her. “It’s the hitman on the

jacket of the British edition of my novel,

Don’t Look Behind You.

Noreen believes Kait was trying to channel the message, ‘It

wasn’t

a random shooting! I was shot by a

drug dealer’s hitman,

like the one in Mother’s book!’”

“If it’s just symbolic, then, that’s okay,” the attorney said. “But we definitely

can’t use the second sketch – the one the psychic says is the politician your daughter

saw do drugs. If that happens to resemble a real person, there might be a libel suit.”

Leaving the documentation with the legal department, I went to another office to meet

with the senior editor and head publicist.

“If we publish this book we’re going to want you to go on tour with it,” the editor

told me. “The subject is a natural for talk shows.”

“I’ve never been on a talk show,” I said nervously.

“Then we’ll get you a media trainer,” the publicist told me.

“A media trainer?” I wasn’t familiar with the term.

“That’s an expert who works with authors who are going on first-time promo tours.

You’ll be taught how to take control of an interview and deal with hecklers.” Seeing

my expression change from doubtful to terrified, he quickly switched to an alternate

line of argument. “You wrote this book to motivate informants, didn’t you?”

“Yes,” I acknowledged.

“A promo tour will make that possible,” the editor pointed out. “That visual exposure

may be just what it takes to bring you the answers you’re looking for. I’ll be in

touch with your agent to work out details. Oh, and one other thing – the book needs

a stronger title.”

“I like

One to the Wolves

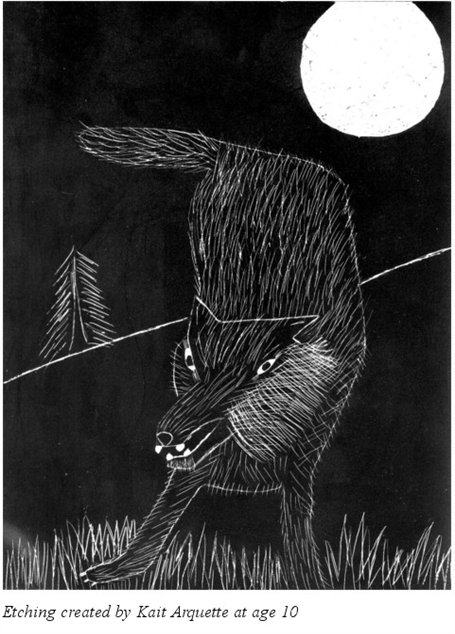

!” I protested. That title held special meaning for me because it reminded me of an

eerie picture of a wolf that Kait had created as an etching when she was ten. Was

it

possible, even back then, she was having nightmares about the “wolf” who would come

for her eight years later?

“I’m afraid that’s too subtle,” the editor said. “We need a title that will jump out

and grab people.”

By the time I left her office,

One to the Wolves

had been re-titled

Who Killed My Daughter?.

I comforted myself with the thought that, if the time ever came that I wrote a sequel,

I would use the “wolf” title.

I had also been assigned to a media trainer named Bill.

My training session consisted of an eight-hour marathon in Bill’s New York office.

“I want to know all about what happened to your daughter,” he told me. “Start at the

beginning and tell me the story chronologically.”

I braced myself and began.

“Kait stopped by our house at six that evening. I'm sure of the time, because

60 Minutes

had just come on. Kait had recently graduated from high school and gotten her own

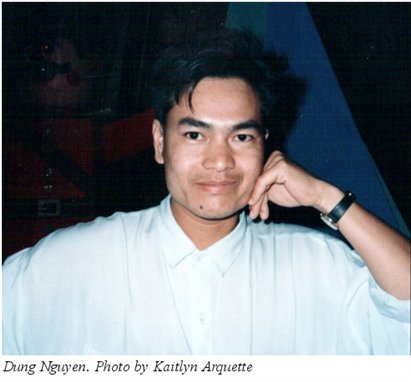

apartment, and she’d let her boyfriend, Dung Nguyen, move in with her.”

“After the murder, her apartment manager told us that a lot had been going on that

Kait hadn’t shared with us. He said Kait was afraid of Dung’s friends and had the

locks changed to keep them out, but they broke a window and got in that way. Another

time, she locked Dung out because he’d threatened her, and he kicked in the door.

When she left our home on the night she was shot, Kait told us she was breaking up

with Dung and was going to spend the evening with a new girlfriend named Susan Smith*,

and if Dung called trying to find her—”

Bill lifted his hand to signal me to stop.

“Let’s take it from the top,” he said. “You need to tighten that up. In your first

sentence, identify Kait by name and say where and when she was shot. In your second

sentence, state the problem you have with the investigation. Save the details for

later.”

I drew a deep breath and started over.

“In July, 1989, our daughter, Kaitlyn Arquette, was murdered in Albuquerque, New Mexico.”

I glanced at Bill for confirmation, and he nodded his approval. “The police called

the shooting a random drive-by, but our family is convinced Kait was killed because

she was getting ready to blow the whistle on interstate crime.”

My detailed rendition of the story took forty-two minutes and left me emotionally

exhausted.

“Pretty good,” Bill said. “Now, let’s try it again.”

“Again?” I exclaimed incredulously.

“Most shows won’t allow you anywhere near that much time,” Bill said. “Let’s say you’re

on a show that allows you only ten minutes. How are you going to condense this to

fit that time frame?”

We worked the story down to ten minutes. Then, to five minutes. And, finally, to three

minutes. One hundred and eighty seconds to describe the circumstances of Kait’s murder

and explain why we believed the shooting was premeditated.

We broke for a hurried lunch and returned for “the hard part.”

“How many TV appearances have you done?” Bill asked me.

“None, except for a couple of local newscasts.”

“Then we’ll need to start you from scratch. Let’s move into the studio.”

The room that connected to Bill’s office was arranged like a stage set. He placed

me in a chair, directed lights at my face, and started a camera rolling. Now, in addition

to worrying about the content of the story, I had to be concerned about the direction

of my eyes, the intensity of my expression and the angle of my head.

“Keep your chin down,” Bill directed. “Tilting your head like that makes you appear

unapproachable. Keep your gestures at chest level so your hands don’t come between

your face and the camera. And if you’re going to cross your legs, do it at the ankles.”

Toward the end of the day we got to the phone-in programs. Bill played devil’s advocate

and goaded me with the types of questions he said I could expect from a call-in audience.

I had grown so accustomed to his empathetic interview style that this new approach

came as a shock.

“Mrs. Arquette — or

Ms. Duncan

, or whatever you want to call yourself — as a member of the Police Benevolent Society,

I’m shocked and offended by your criticism of our boys in blue. Why would they want

to cover up for an Asian crime ring?”

“That’s what we’d like to know!” I shot back. “We trusted the police! We believed

in those shows on television where they follow up on every bit of evidence, and take

statements from all witnesses and suspects, and write honest reports—”

“No!” Bill broke in. “That’s not the way to respond. If you let yourself be provoked

into a display of anger you’ll weaken your credibility.”

“Then how do I answer a question like that one?”

“Take the high road,” Bill told me. “State your position with dignity in as few words

as possible and try not to sound accusatory. Let’s try it again.” He repeated the

question in exactly the same words.

“I don’t want to believe they’re ‘covering up,’” I responded in a gentler voice. “Whenever

Dung was interviewed, he acted like he could hardly speak English. Maybe that scared

the cops off. On the other hand, the case detective told us that they have a Vietnamese

consultant. We don’t understand why he wasn’t called in for those interviews.”

The barrage of challenging questions continued until it was time for me to leave for

the airport.

“You’re going to do just fine,” Bill said reassuringly as he handed me the video of

our training session. “Take this home and analyze it. You’ll learn a lot by viewing

yourself objectively. If you get up-tight about a particular show, feel free to call

me.”

The traffic was lighter than expected, and my cab driver got me to the airport with

time to spare. I checked my luggage, went to the gate and took a seat in the crowded

waiting area. I had a paperback book in my purse but was too tired to read it. Instead,

I replayed the day over and over in my mind, cringing at the memory of the hideous

questions Bill had hurled at me in his well-intentioned effort to prepare me for the

worst that call-in viewers could dish out.

“How could you let your daughter date somebody of another race?”

“What kind of slut was she to let her boyfriend move in with her?”

“Why can’t you put this unfortunate event behind you and get on with your life? You

and your husband still have four living children. That should be enough for anybody.”

His final question had been especially devastating.

“Why would a clean-cut honor student — who had never been in trouble with the law,

who didn’t do drugs, who wouldn’t even smoke a cigarette — become involved with an

organized crime ring?”

I’d asked myself that question a thousand times and still hadn’t found an answer.

Shortly after the shooting, Kait’s sister, Robin, had said to me, “Aside from losing

Kait, the worst thing about this nightmare is knowing that she never had a chance

to make her life meaningful. She had so many dreams for the future, and she couldn’t

fulfill them. I can’t bear the thought that Kait died an empty death.”

So far, I had managed to deal with my personal agony by pouring our on-going horror

story onto paper. But what would I do with my pain now that the book was completed

and I no longer had that outlet?

A wave of dizziness struck me and the world became suddenly diffused as if a movie

projector had slipped out of focus. My ears were filled with the sound of my accelerated

heartbeat and I gripped the arms of my seat to keep from falling out of my chair.

The anxiety attack seemed to last for no more than a minute but when I opened my eyes

I found that the waiting room was empty. I glanced about me in bewilderment — where

had all the people gone? Then I looked at my watch and discovered that over half an

hour had passed since I last had been conscious of the world around me.

I got up and went over to the counter.

“Where is everybody?” I asked the attendant. “Has the gate been changed?”

“No, ma’am,” he said with a smirk.

“So, how late is the flight?”

“It was right on time,” he told me. “It took off ten minutes ago just like it was

supposed to.”

“But I didn’t hear you call it!”

“That’s your problem, lady. Fifty people walked right over your feet to get on it

and you just sat there.”

That was when I realized that my kind media trainer had overestimated my resilience.

I was

not

going to be “just fine.”