One to the Wolves, On the Trail of a Killer (10 page)

Read One to the Wolves, On the Trail of a Killer Online

Authors: Lois Duncan

Since Pat was convinced that our answers lay at the crime scene, we decided that she

should concentrate her main efforts there. We made up a list of people she should

try to interview, including the first two officers at the scene, the medics who transported

Kait to the hospital, and the witnesses who saw the VW bug pull into the parking lot.

She would also try to locate Paul Apodaca, although that was not going to be easy,

since the police had not obtained any identifiers.

We also decided it was time to take assertive action to get back the materials from

Kait’s desk.

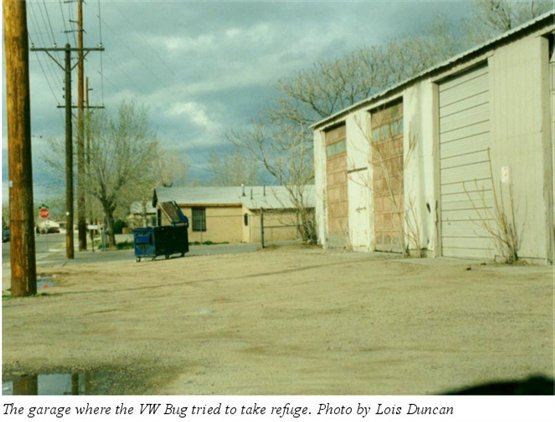

The first thing Don and I did after leaving Pat’s office was drive over to look at

the body shop. It was a large multi-bay garage on a double lot. Along one side of

the building and extending around behind it, there was a fenced area, the gate to

which was padlocked.

Why had the VW bug gone straight to that site? Were the killers familiar with the

area and aware of the Dumpster? Had they tossed a weapon into it? Had a passenger

been dropped off? Had they planned to hide in the storage area and found it locked?

Back in 1990, when Juve Escobedo had abruptly vanished, I had asked Betty Muench to

do a reading to see if he was dead. Betty had assured me that Juve was alive and said

he was confined in a garage in Albuquerque.

“I don’t get a sense that he’s being held by the Vietnamese,” she had said. “It seems

like somebody in authority is acting independently without the people he works with

knowing what he’s doing.”

That had made no sense at the time, but now, right here in front of us, was a garage

that had been identified as a hangout for cops like Matt Griffin. On the day the bench

warrant was issued for Juve’s arrest, he had been on the phone with his girlfriend

and suddenly told her, “Well, the police are outside now. The next time I talk to

you, I guess it will be from jail.” Then he’d vanished and didn’t reappear until the

charges were dropped. Whatever those cops had come for, it wasn’t to arrest him.

If they’d taken him somewhere, it certainly hadn’t been to jail.

We’d given Pat power of attorney, and she was able to get permission to inventory

Kait’s personal belongings under the supervision of an evidence room technician. When

she did so she found that the materials from Kait’s desk were not there. According

to the evidence room log, Detective Gallegos had misled us. Kait’s personal belongings

never had been entered into evidence.

Soon after that we received a call from a woman in Albuquerque with information about

something else that was missing.

“I’ve come across one of your family videos,” she told me.

The shock was so great that for a moment I couldn’t get my breath.

“Where in the world did you find it?”

“At one of those places where you buy used tapes,” the caller told me. “I don’t usually

look at those tapes before I record over them, but this time, for some reason, I decided

to watch it, and there was

Donnie

! He and I went to school together, and I helped circulate your reward flyers. Kait

appears on this tape, and before I erased it, I wanted to check and make sure you

really didn’t want it.”

“We want it,” I said. “Yes, we want it! God bless you for calling us!”

I told her where to mail it.

Another winter was upon us, bringing with it the holiday season and, like a blow to

the heart, a new calendar. What right did it have to be 1995 when we had not yet closed

the door on 1989? When we thought back upon the people that we had been immediately

after Kait’s death, reluctant to leave the house for fear of missing the call that

would tell us her killers had been arrested, it was like remembering ridiculous overgrown

children who still believed in Santa Claus. Back then there had been no way that we

ever could have imagined that six years later we still would be waiting for that call.

The mystery of the missing videos continued to haunt us. They hadn’t been lost after

all, they were back in Albuquerque, and at least one of them had been discarded by

whoever had taken them. But why would anyone want to steal those videos? The tape

Donnie’s friend had returned to us was mostly of a nephew’s wedding. Toward the end

of the tape Kait made a cameo appearance at a cookout, and we watched, spellbound,

mesmerized by such simple wonders as the sight of her spilling catsup on her shirt

and the sound of her voice squabbling with one of her brothers. But although such

scenes evoked memories that were precious to us, there was nothing on tapes like that

one to make it worth anyone’s while to break into our house and take them.

But, then, we reminded ourselves, there had not been a break-in. The thief had apparently

had a key.

“Dung and his friends sometimes used Kait’s car,” Don said. “Our house key was on

her key ring. It would have been easy for one of them to make a copy, and Dung knew

where we kept the family videos. He used to watch them with Kait.”

But what had been on those videos that made them worth stealing? We couldn’t think

of a thing.

In the spring, I was asked to serve as replacement for the dinner speaker at a convention

of fraud investigators in Austin, Texas. Don suggested that I make a stopover in New

Mexico to meet with the State Attorney General and make him aware of the problems

we were having with the police investigation.

Pat set up the appointment and put together a packet of information. She also obtained

tapes of all the interviews conducted by Miguel Garcia’s defense attorneys and invited

our new investigator friend, Roy Nolan, to meet with us to discuss them.

“It’s no wonder Schwartz wasn’t willing to prosecute,” Pat told us. “The case against

the Hispanics was non-existent. Even if the witnesses had been credible, which they

weren’t, the case would have been thrown out because of fabricated evidence. The police

re-transcribed a tape to reverse its meaning. They couldn’t have expected to get away

with something that obvious. It’s almost as if they wanted the Hispanic suspects to

get off.”

“Maybe they did,” Nolan speculated. “All it took to shut down the investigation was

an arrest. There didn’t have to be a conviction.”

“You think they may have arrested the Hispanics even though they knew they weren’t

guilty!” I exclaimed.

“That happens quite often,” Nolan said. “A lot of times it’s with the cooperation

of the suspects. Most narcs have a stable of snitches who do whatever they’re told

to in exchange for protection from arrest for more serious crimes. People like that

can earn money and favors by cooling their heels in jail for a while, knowing they’ll

never be convicted.”

“But Miguel sat in jail for fifteen months!” I protested. “That’s an awfully long

time for a nineteen-year-old kid to ‘cool his heels’.”

“He was due to serve that much time anyway for an unrelated burglary,” Pat pointed

out. “Schwartz dropped the burglary charges without explanation at the same time he

dropped the homicide charges, so Miguel just traded one stint of jail time for another.

And Juve didn’t serve any time at all.”

“Marty Martinez didn’t serve time either,” I said. “Police didn’t even take a statement

when he called and confessed. If the arrest of the Hispanics was just for show, and

the police didn’t want them to be prosecuted—”

“That would explain Marty’s statement when he was questioned by the assistant DA,”

Pat said. “He said, ‘The whole thing was a hoax, you know.’”

“Marty’s confession would have wrecked the game plan,” Nolan said. “Marty’s a loose

cannon. He may have been so drunk that night that he didn’t remember afterward exactly

what they’d been hired to do— intimidate Kait or kill her. All he knew was that he

got paid a hundred dollars. The bottom line is, APD didn’t want Marty confessing to

murder for hire. They wanted him to shut up and go away.”

“My question is, who controlled the investigation?” Pat said. “Who had the power to

make the determination that the case

was ‘over’ when the DA told police to investigate the Vietnamese?”

“What about the Vietnamese consultant whose son was Dung’s friend?” I asked. “Would

he have had that kind of influence?”

6

“That ‘consultant’ is in business with some very sleazy characters,” Nolan told me.

“One of them is under federal investigation for trading gold for cocaine. Almost all

major crime in this state comes back to the drug scene. Small time dealers like Peter

Klunck get killed. The guys at the top are in high level political positions.”

“None of that explains what went wrong at the scene,” Pat said. “

That’s

where the cover-up started.”

“I’ll try to find out what happened that night,” Nolan said.

“Be careful,” Pat cautioned. “You don’t want to rattle the wrong cage.”

“I know what I’m doing,” Nolan told her. “I’ll make a few calls and get back with

you. Where are you staying, Lois?”

I told him the name of my motel.

That night, reeling from jet lag, I went to bed early, only to be jerked into consciousness

several hours later by the blast of the telephone. I groped in the dark for the receiver,

and when I finally located it, it took me a moment to recognize the staccato that

ripped into my ear as the voice of the unflappable, street smart investigator with

whom I had spent the afternoon.

“We were totally off base,” Nolan said urgently. “The cops who handled the crime scene

are clean as the driven snow.”

“How do you know?” I asked, still groggy with sleep.

“Just take my word for it,” Nolan told me. “There wasn’t a cover-up, Lois. And we

were wrong about the motive for Kait’s murder. She was the victim of a car-jacking.”

“

What

?” I was fully awake now and couldn’t believe what I was hearing.

“Paul Apodaca was a car-jacker. That’s the only thing that makes sense.”

“But what about the car wrecks and drug dealing?”

“The Vietnamese had nothing to do with this case,” Nolan insisted. “And drugs didn’t

play any part in it. This was a car-jacking, pure and simple. There’s no other possibility.”

“I don’t buy that,” I said.

“You’ve got to believe me, Lois!”

“I don’t buy it,” I repeated and hung up the phone.

Nothing about the outrageous scenario was credible. Was I really supposed to believe

that Paul Apodaca was standing on the sidewalk, drinking a Budweiser, and became so

enamored of Kait’s five year old Ford Tempo as she drove past that he shot her? Then

he set his beer can down on the curb, leapt into his VW and drove to the auto body

shop, where he disposed of his weapon in a Dumpster, made a U-turn and returned to

the scene of the shooting, just in time to cozy up to an off duty police officer,

while his own car left the scene all by itself without a driver?

Obviously something had happened since I’d last seen Nolan, and whatever it was had

him terrified, either for himself or for me. In his effort to get information, he

must have gone to the wrong person.

It struck me that I might have made a very bad mistake. I should have pretended to

accept the car-jacking story. Now they — whoever the mysterious “they” might be —

would have to find another way to convince me, and that might take a rougher form

than a friendly phone call.

A chill swept over me as I envisioned one of Matt Griffin’s buddies arriving at my

door. How could I refuse to open up to the police? It was hard to imagine the type

of person who could intimidate a man like Roy Nolan, and I wasn’t in a hurry to find

out.

I threw on my clothes, grabbed my suitcase, and left the motel room. The light above

the doorway shone down like a spotlight, and I had never felt more vulnerable in my

life than I did as I stood there fumbling in my purse for my car keys. I found them,

got into the car, and pulled out of the parking lot onto a street as deserted as the

one that Kait had been driving on the night she was shot. I could visualize the headline—

“Mother Imitates Daughter — Random Shootings Run In Family”

— a natural for the

National Enquirer.

It seemed like forever before I spotted a motel with a vacancy sign. I pulled in and

took a room for the remainder of the night, and the first thing in the morning, drove

to the airport to trade in my eye-catching teal rental car for a car of a different

make and color.

It was possible that Nolan had noticed what I was driving.

In my innocuous new vehicle — (I had specified that I wanted something “inconspicuous

and grungy,” a request that had not gone down well with the people at Avis) — I drove

to Pat’s office.

“Where have you been?” she demanded. “Roy Nolan has been trying to locate you. He

says he’s checked out all the cops connected with Kait’s case, and they’re clean as

the driven snow. He tried to call you this morning, and when you didn’t pick up he

got worried. He asked me what kind of car you were driving.”

“Why did he want to know that?”

“I don’t know what he was thinking. Maybe he was going to try to look for you. He

seemed very concerned that you’d left your motel without telling us.”

“Did he tell you Kait was shot during a car-jacking?” I asked her.

“Of course not,” Pat said. “That’s ridiculous.”

“We’ve lost Roy Nolan,” I said.

7

When I told her about Nolan’s late night phone call, she shook her head in bewilderment.

“Maybe he’d been drinking?” she suggested.

“He didn’t sound drunk, he sounded frantic.”

That was the day we were scheduled to meet with the State Attorney General, but that

didn’t happen. He stood us up, and we were relegated to a new assistant AG who reluctantly

accepted Pat’s case materials. We knew when we left his office that we wouldn’t be

hearing from him.

Faced with an unexpected block of free time, I decided to pay a visit to Renee Klunck.

The federal grand jury had now concluded their civil rights investigation of Peter’s

death and no indictments had been returned. According to a statement by the U.S. Attorney,

the case was too old and there was too much conflicting testimony to charge Griffin

or any member of the police department with criminal conduct. “Accurate recollections

fade with time,” he said. “No one can now say with certainty exactly what happened

on the morning of January 27, 1989.”

Renee, though disappointed, had accepted the inevitable.

“At least, they didn’t find the shooting justified,” she said.

“Did Peter ever mention an auto repair shop on Arno Street?” I asked her as we settled

ourselves at her breakfast bar with our cups of coffee.

“Not that I recall,” Renee said, but the Kluncks’ youngest son Danny, who had wandered

into the kitchen to make himself a sandwich, overheard the question.

“I know where that is,” he said. “Pete used to do off-the-books body work for those

people. I know he worked at that shop in December of 1988, because that’s where he

took the dents out of my car.”

“But that would mean—” Renee sent her coffee cup crashing to the counter as the significance

of that statement hit her. “That would mean that, one month before Griffin shot him,

Peter was working at a location where Griffin hung out! For six years the cops have

insisted there was no possible way that Griffin and Peter could have known each other.

Now we find out they were right in each other’s pockets!”

“Do you know if Peter had Vietnamese friends?” I asked Danny.

“No, but Griffin did,” he told me. “The first time I ran into Griffin, before all

this shit came down, he was in a parking lot in the Northeast Heights with a bunch

of guys on motorcycles. A lot of those bikers were Vietnamese.”

At the end of the day I flew to Austin to speak at the conference of fraud specialists.

Michael Bush flew in from L.A. to provide emotional support, bringing with him his

friend Leslie Kim, the editor of a national trade paper for insurance claims investigators.

The investigators were an intimidating group to speak to, especially when I discovered

that the speaker I was there to replace was Texas Governor George W. Bush. After my

presentation I asked for questions and was confronted by stony silence from a roomful

of deadpan, primarily male, investigators. Too drained and discouraged to make even

a token attempt at socializing, I made my apologies to Michael and his editor friend

and headed up to my hotel room.