One to the Wolves, On the Trail of a Killer (17 page)

Read One to the Wolves, On the Trail of a Killer Online

Authors: Lois Duncan

“It sounds like that’s going to keep him busy,” Don commented. “Too busy, I guess,

to follow up on any of the other stuff.”

To us it seemed oddly coincidental that this eyewitness would suddenly pop up after

fifteen years. The term “resurfaced” implied she was already known. If her information

was so important and incriminating, why had Bob Schwartz decided not to prosecute?

The whole situation felt suspect, and we couldn’t help wondering if this honest detective

— an obvious threat to a cover-up — had been served up a manufactured witness in a

deliberate attempt to divert his attention from Pat’s information. If so, there had

to be some way to get him re-focused.

“I’ve heard there’s now an excellent ballistics expert at APD,” I said. “Perhaps

the detective would be willing to ask him to compare the partial bullet from the door

frame with the minute bullet fragments from Kait’s head. He did say forensic science

was the key to solving cases.”

“If bullet fragments are incriminating evidence, what makes you think they still exist?”

Don asked doubtfully.

“They

have

to exist,” I insisted. “They were checked into evidence. All the things in the evidence

room are protected.”

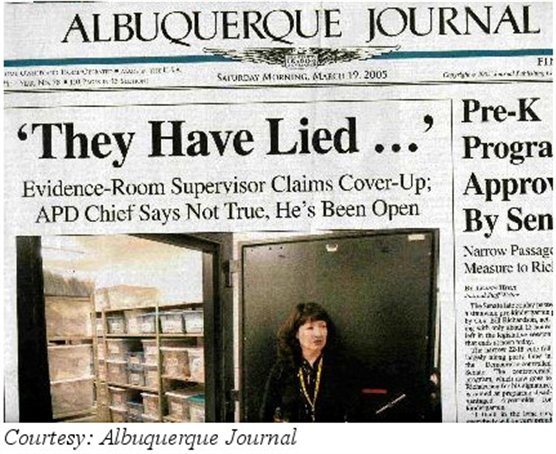

The irony of that statement became apparent when we pulled up the on-line edition

of the

Albuquerque Journal

and were faced with a banner headline:

CLEANUP DESTROYED APD EVIDENCE

According to the article, evidence from hundreds of cases, most of them drug related,

had been destroyed at the Albuquerque Police Department during the cleanup of hazardous

chemicals, which had been spilled on evidence bags.

Apparently, nothing in the evidence room was protected.

The chemical spill was the tip of the iceberg.

The Attorney General’s Office received an anonymous letter claiming that for many

years police employees had been stealing huge amounts of cash, drugs, guns and other

valuable items from the evidence room and APD management had covered that up.

The current police chief was quick to deny the accusation. To reinforce that denial,

he invited the media to tour the evidence room. During the tour, Sergeant Cynthia

Orr seemed reluctant to answer questions and asked her supervisor if she had permission

to speak freely. He assured her that the department wanted them to be open and honest,

so Sergeant Orr invited a reporter into her office and agreed to be recorded.

The sergeant told the reporter that the police chief had lied to the public and had

failed to act despite repeated warnings of evidence theft. Orr said that she, personally,

had identified two individuals who were stealing in the evidence room, but the chief

had allowed them to continue to work there. She went on to describe how officers

under criminal investigation were allowed to work in the evidence room where they

were free to tamper with the evidence in their own cases. Orr said she was told not

to send reports about missing evidence to the records division because the Top Brass

didn’t want it to become public record that items were missing.

“Am I implicating the chief in assisting in this cover-up? Absolutely,” Orr said.

“Do I know this is a dangerous accusation to make? Absolutely. But I know this is

something that needs to be done.”

USA Today

picked up the story and it went viral. “The APD Evidence Room Scandal,” as it came

to be known, continued to accelerate as additional whistle-blowers gained the courage

to come forward. The list of valuable property that had been sold at auction or “taken

to the dump,” (which we assumed meant employees took it home with them), grew longer

and longer. An example of such items was a $15,000 plasma television set, which was

seized as evidence in a white-collar crime investigation and was supposed to be returned

to the owner after the trial. Evidence room personnel said they “took the TV to the

dump” because it had a crack in it.

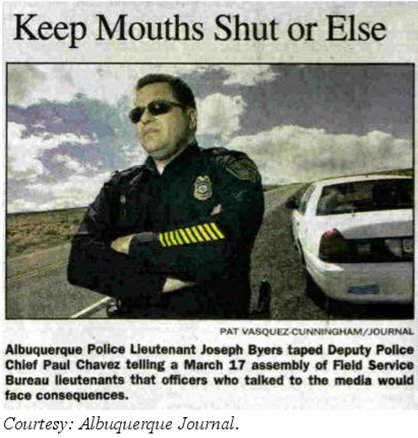

There was instant retaliation against the whistleblowers. A captain, who had reported

the damage from the chemical spill, was asked to turn in her badge, gun and squad

car. A different captain, who had ordered an investigation into high-ranking members

of the police department, was punished by having the Internal Affairs division taken

away from his command. At two citywide meetings, attended by hundreds of officers

who were required to be there, deputy chiefs encouraged them to be “angry and repulsed”

by Sergeant Orr for breaking the code of silence.

In a furious tirade, filled with profanity, one deputy chief warned his lieutenants

that if they ever openly criticized the administration he would yank them from their

command. One lieutenant taped that diatribe and filed a complaint with the City’s

Labor Management Relations Board.

“He was trying to intimidate us,” the lieutenant stated. “Others will not come forward

because they are scared.”

Back in 1994, in response to my question, “How is this going to end? “ Betty Muench

had told me:

“There is this group which is not understanding how things operate and they will be

making their own rules. When this will border on anarchy, then they will fall, with

truth coming out all around.”

Was this the beginning of the fall? I certainly hoped so. My father had once remarked

humorously, “Life is like a roll of toilet paper – the closer you get to the end,

the faster it goes.” At the time, I had thought that was funny. It wasn’t funny now.

When I’d stood at Kait’s gravesite and told her, “Mother is going to get your killers,”

I couldn’t have imagined how long that would take. Now I was feeling threatened by

my own mortality.

The mayor told reporters, “When you have a department where there are accusations,

counter-accusations, lieutenants accusing captains, captains accusing deputy chiefs,

that is a department in disarray.”

In the wake of that statement, the police chief resigned. He was given a hero’s send-off

by the police union, who threw a huge retirement party in his honor.

Experts were imported from California to analyze the evidence room problems. One of

their suggestions was “Stop storing so much stuff!” Although valuable items were missing,

(one woman had already filed a law suit claiming police had “misplaced” $100,000 worth

of her family jewelry), there were over one million pieces of evidence crammed into

the APD storage area.

The evidence room manager began to dispose of the items by selling them on E-Bay.

The threat of a major purge threw us into a panic about the items from Kait’s desk.

Her personal property, including her telephone book, snapshots, and correspondence,

might easily be considered disposable after fifteen years. Don submitted yet another

request for their return, citing our concern for their safety. The new District Attorney

agreed that we could have them. The Vietnamese correspondence was missing from the

materials, but we now had pictures of some of Dung’s friends in California. Not that

they had any value, since the statute of limitations on the car wreck insurance fraud

had long since run out.

The evidence room circus continued to provide entertainment for the nation. According

to one article, three months earlier, a freezer in the evidence room that contained

more than 1,600 samples of blood, urine, saliva and other evidence from rapes and

homicides had been shut down. It was hardworking Sergeant Orr, who, although off duty

that day, responded to a security alarm in the evidence room to find a door standing

open. When she checked out the rest of the building she detected a foul stench and

discovered the freezer had a temperature of sixty-eight degrees. The police and prosecutors

had withheld that information from defense attorneys, who continued to construct their

cases on contaminated evidence.

Although DNA evidence wasn’t a factor in Kait’s case, it was crucial to some of the

other cases on our website. We hoped that those cases were not among the ones affected,

because many of our Real Crimes families were depressed enough already. Several, who

had been optimistic about breakthroughs, had been crushed to discover their cases

could not be prosecuted.

Update

— Nancy Grice’s daughter, Melanie McCracken:

A grand jury indicted Melanie’s husband, now-retired State Police Lieutenant Mark

McCracken, on charges of first-degree murder and tampering with evidence. But the

charges were dismissed on a technicality — an investigator for the prosecution was

in the room during testimony.

Update

– Bill Houston’s daughter, Stephanie Houston:

The boyfriend who ran Stephanie over with his truck was brought to trial, but a jury

found him not guilty of vehicular homicide. Police had not interviewed witnesses at

the time of the incident, and, now that the case was four years old, the prosecutor

would not call them.

Update

— Arry Frank’s sister, Stephane Murphey:

A judge declared the key jailhouse statement that incriminated David Bologh inadmissible

because police had neglected to have him sign a waiver of his rights before taking

his statement.

The district attorney said he would appeal the judge’s ruling.

“We hear the appeal may take two or three years, “said Stephane’s mother, who had

driven 1,000 miles from out of state to attend a trial that did not take place. “It

feels like we’re being tortured. We’re being twisted slowly over a fire.”

On Mother’s Day, 2005, I experienced one of those dreams that left me feeling that

I had received a message. It was the first such dream I’d had in over five years.

But this time it wasn’t Kait who delivered the message. The visitor who appeared at

my bedside was the last person I would have expected, even in a dream.

It was Miguel Garcia.

Although I never had seen him in person, I immediately recognized him from newspaper

photos. In the dream he was not in his thirties, as he would have been now, but was

still the pimply-faced kid he had been when Kait was murdered.

Miguel handed me a Mother’s Day card with a picture of the Virgin Mary on the front.

When I opened the card, the message read, “I DIDN’T DO IT.”

I looked up at the boy, who was standing there, waiting expectantly.

“If you didn’t, who did?” I asked him.

Miguel said, “Juve.” He paused and then added a bit nervously, “She told me to give

you a hug because it’s Mother’s Day.”

I didn’t know if he was referring to the Holy Mother or to Kait, but either one was

acceptable. In my dream state, I got out of bed and let him hug me. He was a strong

but skinny kid, not much taller than I was, and it felt like being hugged by my teenage

grandson.

Then Miguel’s image disappeared, and I was awake.

I got out of bed, went into my home office, and recorded the dream. I had no idea

what the source was— “Mary, Mother of Heartbreak”; Kait, reaching out to me on Mother’s

Day; or Miguel himself, asleep in Albuquerque, dreaming with such ferocity that his

dream crossed the miles between us and merged with my own. I decided I would treat

this information as I would any other tip. I would consider it a possibility until

it was disproved.

Juve Escobedo? The man was an enigma.

APD’s preferential treatment of Juve had always seemed strange. Although the men were

arrested at the same time, police had held only Miguel. Even after both were indicted

and a bench warrant was issued for Juve, police had not picked him up.

Over and over, psychics had described a shooter who sounded like Juve. Robert Petro

had said

,

“He has a very unusual first name, like a nickname. He appears to be around five feet

eight, about 175 pounds, he has a police record, and he has somewhat dark skin, and

he has what look like tattoos.”

Shelly Peck had been even more explicit

: “I’m getting a short name that starts with J. John? Joseph? And a Michael is involved

somehow. And there’s an S name. Or — ‘ES’ — something? Was this person a mechanic?

I get him disassembling cars. I get a vision of gas tanks, which is the symbol for

a garage. Does he work in a garage, taking cars apart?”

There was no way I could have influenced Shelly to make such statements. At the time

of her reading I had not known about the body shop.

If Juve was connected to that, he quite possibly had disassembled cars. And Betty

Muench had definitely placed him at that shop.

“The Hispan

ic suspect, Juve Escobedo, was there,”

she had written during one of her trance readings.

“This was after the death of Kait. He enters midst much attention and a sense of expectancy.

He is to receive something.”

So how did my current Dream Visitor fit into the picture?

According to Betty,

“Garcia sought this so called ‘honor’ and must now undergo the pressure.”

Was it possible that Miguel had accepted the assignment and hired the others as accomplices?

In one of his drunken confessions, Marty had told police that he was paid one hundred

dollars.

I went to the computer and pulled up information about Miguel. In February 1989, a

warrant had been issued for his arrest for “aggravated assault.” When I looked up

the definition of that charge, it was, “An unlawful attack by one person upon another

which results in severe or aggravated bodily injury and/or is accompanied by the use

of a weapon or by means likely to produce death or great bodily harm.” That was a

very strong charge. What had Miguel done? I went back to the database to read the

report by the officer who had gone to his home to arrest him.

It said a complaint had been made that Miguel had thrown an unknown object at a truck.

That came nowhere near meeting the criterion for “aggravated assault.” However, the

accusation of a felony, even if unfounded, had made it possible for that officer to

obtain a warrant that allowed him to enter Miguel’s home. Surprisingly, though, the

officer hadn’t arrested him. They’d apparently just had a chat and the cop had left.

In his report he had listed an incorrect house number so people who read the report

wouldn’t know where Miguel lived.

Who was the cop who misrepresented the offense and then magnanimously let the fish

off the hook?

I caught my breath as I realized why the name was so familiar.

He was the brother of Paul Apodaca’s drug dealer, Lee.

The implications of such a situation were overwhelming. Roy Nolan had told Pat and

me that narcs kept a stable of snitches who accepted assignments in exchange for money

and protection. Miguel was in debt to this officer for not arresting him for “aggravated

assault.” Four months later, might he have been called to ante up?

But, even if Miguel had agreed to terrorize Kait, that didn’t mean that he killed

her. When police raided his home, they had found only one live cartridge and a single

action revolver loaded with blanks. Blanks suggested intimidation, not murder. No

blanks had been found in Juve’s arsenal. Might Juve have been privately commissioned

to kill Kait, while Miguel and Marty thought they were just going to scare her?