One to the Wolves, On the Trail of a Killer (14 page)

Read One to the Wolves, On the Trail of a Killer Online

Authors: Lois Duncan

Albuquerque now had a new mayor, Jim Baca, who was doing his best to deal with the

problems he’d fallen heir to. In response to newspaper headlines claiming, “THE CITIZENS

OF ALBUQUERQUE ARE AFRAID OF THEIR COPS,” Mayor Baca imported a new police chief from

out of state to replace Joseph Polisar and was attempting to establish a citizen review

board for police-misconduct cases.

“The police department has to be accountable to somebody besides themselves,” Baca

stated.

The police union was not happy with Mayor Baca’s attitude.

The president of the Albuquerque Police Officers Association told the media,

“If he screws with us, we will do everything possible to defeat him in the next election.”

Which they did.

The union strenuously objected to the idea of a review board. They contended that

the Internal Affairs unit was more than sufficient to deal with charges of misconduct,

despite the fact that for the past three years excessive force charges against police

officers that were found to have merit had resulted in nothing more than written or

oral reprimands.

“Letters of reprimand for beating the hell out of people is not enough,” said the

director of Vecinos United, a group that had long decried continual civil and human

rights violations by APD.

As the debate raged on, I received a call from Patti March, a founder of the New Mexico

Survivors of Homicide.

Patti’s son, Gary, had been murdered in Albuquerque in 1995.

“I read your book because I was told by a homicide detective that my family was a

pain in the ass, just like the Arquettes,” Patti told me. “We were doing the same

things you did — talking to people the cops didn’t talk to, printing flyers and trying

to pressure the police to follow up on leads.”

Patti told me that one of the mothers in the survivors group thought her son’s murder

might be linked in some way to Kait’s. Of course, I phoned her.

Carmen Haar turned out to be the ultimate homicide survivor. Her son, Stephen, who

had been shot to death in January 1998, was the

third

of Carmen’s children to die a violent death.

“Steve had been estranged from the family because of his drug use,” Carmen told me.

“In the month before he was killed he tried to make amends. Steve told me twice,

‘Mom, they’re going to kill me.’ I asked, ‘Who is going to kill you?’ He said, ‘These

are high profile people. It’s best that you don’t know.’ I said, ‘You’re talking crazy.

You think ‘high profile people’ kill people?’ Steve said, ‘They don’t have to. Others

do it for them.’”

“Do you know who killed Steve?” I asked her.

“A man named Travis Daley confessed to the shooting, but he claims self-defense, so

the police won’t charge him. How can it be self-defense when Steve was shot in the

back? After Steve’s death, I found a note in his pants pocket warning him about a

contract that had been put out on him. I believe Steve was killed for the same reason

Peter Klunck was — he knew too much about VIPs who were involved in the drug scene.

Steve and Peter knew each other. Both did body work on cars. And both of them knew

Matt Griffin.”

When Pat ran the information about Steve Haar through her database, she did find a

strange link to Kait’s case. At the time of Steve’s murder, he had lived at the same

address as the witness who had told police he saw Kait followed from her apartment

by a VW bug.

On August 4, 1998, the nurse, Nancy Grice, filed a federal civil rights suit against

her former son-in-law, New Mexico State Police Sergeant Mark McCracken, and the state

police chief. She accomplished that just one day before the statute of limitations

ran out. “I couldn’t get a lawyer, so I read some books and learned how to do it myself,”

she told me. Her suit was later amended to name other individual officers and the

State Police in their official capacity. Nancy then petitioned the court to appoint

an attorney for her and had Melanie’s file submitted for review by a forensic expert.

Meanwhile, I had been contacted by yet another mother whose child had died in Albuquerque

under suspicious circumstances. Jennifer Vihel’s son, Josh, 16, had died of apparent

alcohol poisoning at a party, but the fact that there were bruises on his body and

money missing from his wallet caused his family to suspect foul play. Police claimed

they were unable to question the party-givers, because they couldn’t find their house.

Josh’s sister conducted her own investigation. She located the house with no problem

and interviewed the neighbors, who told her the owners of the house threw frequent

parties at which they charged cover fees and sold liquor and drugs to minors.

“One neighbor said she called in four complaints and no one ever did anything,” Jennifer

said.

I added

“Jennifer’s son, Josh Vihel”

to my Tally Keeper notebook.

It had been a long time since I’d last consulted a psychic. In recent years my focus

had been on practical matters — forensic data, crime scene evidence — things that

could be used in court. Now, however, I found myself yearning for something more.

I needed reassurance that there was still hope for all of us — that, as bad as things

seemed, there was a Master Plan and we were part of it.

So I wrote to Betty Muench with yet another question:

“How is this going to end, or will there ever be an ending?”

Betty mailed me her reading:

“There will be this which will go beyond the enforcement officers of the law, for

none locally can be trusted with this. But there will be other legal activity which

will be connected to this. This will have to do with the infiltrating of certain groups,

and this can only be done by

men.

This will have to be very assertive and aggressive and will ultimately require the

use of the authorities in the manner of certain police actions. It will be like starting

from the top and tracing all this information downward.

“

There will be a final need to act, which will require the use of the highest form

of policing, and that will be the federal level. There will be for Lois the continuing

battle to put these pieces together, but there will come those with high integrity

who can be trusted, and they will work with what she has already, and this will aid

her greatly in the finding of those who will have knowledge of Kait’s murder.

“Right now there is this group which is not understanding how things operate and they

will be making their own rules. When this will border on anarchy, they will fall,

with truth coming out all around.”

From the Tally Keeper’s notebook:

New case

— Janie Phelps’s son, Sal Martinez:

Sal arrived late at a bachelor party and was shot as he walked in the door. He was

still alive when police got there, but the officers wouldn’t perform CPR because they

had forgotten their plastic mouthpieces. Police said they couldn’t charge the admitted

killer because he claimed self-defense, although Sal wasn’t carrying a weapon, nor

was anyone else at the party except the killer.

New Case

— Valerie Duran’s sister, Ramona Duran:

Ramona was found dead of a drug overdose in the apartment of two men with criminal

records. There was a strong odor of gas, and Ramona had bruises on her arms. The first

officer at the scene termed it “a suspicious death”. A neighbor reported hearing a

woman screaming. Ramona’s family believes she was sedated with gas and forcibly injected

with drugs. Ramona had told family members she feared for her life, because she had

fingered VIPs in the drug trade.

Update

— Nancy’s Grice’s daughter, Melanie McCracken:

Dr. John Smialek, expert witness in forensic pathology, issued a written opinion that

Melanie died as a result of “homicidal suffocation.” When it began to appear that

the case might turn into a murder case, Nancy’s court appointed attorney succumbed

to pressure to settle out of court. The State Police then promoted Sergeant McCracken

to the rank of lieutenant.

Update

— Carmen Haar’s son, Stephen Haar:

Police told reporters they were forwarding Stephen’s case to the District Attorney.

Months went by, and nothing happened. Carmen finally contacted the DA’s office to

ask why charges hadn’t been filed. They told her APD had not sent them the case file.

In the fall of the year, a movie loosely based upon my novel,

I Know What You Did Last Summer,

opened in theaters around the country. This was my first box office movie and I was

ecstatic until I settled into a theater seat and discovered that Hollywood had turned

my story into a slasher film. The first thing I did after leaving the theater was

phone our daughter, Kerry, and warn her not to let the grandchildren see it.

The positive side of this misadventure was that I had been paid for the film rights.

We used part of that money to post a reward for new information about Kait’s murder

and donated the rest to help Pat turn her investigations agency non-profit so she

could provide pro bono services to other crime victims.

We placed announcements about the reward in Albuquerque papers and mailed flyers to

everyone remotely connected to the case. Among those were Dung and his girlfriend

from Oregon.

The girlfriend reacted by calling the police. Since Pat’s office number was on the

flyer, she was the one police contacted with the harassment complaint. Pat explained

that the reward offer was genuine and the girlfriend had not been specifically targeted,

as we had mailed out over three hundred flyers. The officer seemed somewhat mollified

but requested that Dung and his girlfriend be removed from our mailing list.

Then the girlfriend contacted Pat to accuse us of sending threatening letters and

stalking her. Pat told her truthfully that we weren’t doing either of those things.

“She said you sent Dung a video of one of Kait’s birthday parties,” Pat told me. “She

found that very upsetting.”

“I didn’t send Dung any video!” I said. “Our family videos were stolen before we left

Albuquerque.”

“Well, I guess Dung’s got one of them,” Pat said.

Not long after that I received a frantic e-mail from Susan Smith. She, too, was receiving

threatening messages in the mail and suspected that someone was stalking her.

We couldn’t blame the two women for being frightened, since the incidents they described

came right on the heels of our reward offer, and they were obvious candidates to claim

that reward. Susan, who was the last person Kait spoke with before the shooting, and

Dung’s current girlfriend, who was regularly exposed to the same people and activities

that Kait had been, might reasonably have been suspected of having access to the same

information Kait did.

By now Pat had found two more witnesses, Bette Clark and Kathy Baca, the medical team

who had transported Kait to the hospital. Locating them hadn’t been easy, since Cop

Number One had incorrectly identified a male ambulance team as first at the scene.

The only reference to Bette and Kathy was in a report that they, themselves, had filed

at the hospital.

Kathy was now a member of an emergency medical helicopter team, and Bette was a captain

with the Albuquerque Fire Department.

Pat interviewed the women individually and then together, and their memories of that

night were identical.

“What did you see when you got there?” Pat asked them.

“Nothing,” Kathy told her. “I remember it was very dark. It was so quiet it was eerie.”

“I remember that too,” Bette said. “There was a red car up against a utility pole

on the sidewalk. I don’t know who could have made the call, because nobody was there.”

“

Nobody was there!

” Pat exclaimed. “An off duty police detective stumbled onto the scene right after

the shooting. He says he’s the one who called for rescue.”

“Then, where did he go?” Kathy asked her.

“A second, uniformed, female officer arrived at the scene in less than one minute,”

Pat continued. “She was dispatched to an accident without injuries and saw the detective

standing behind Kait’s car, talking with a young man. She assumed that man was the

driver of the red car, because no other cars were there. The detective told her, ‘Don’t

worry, rescue is en route.’ She said, ‘Rescue? Why do we need rescue? He looks fine

to me.’ The detective said, ‘No, we have a victim.’”

“Those people were there

before we were

?” Kathy exclaimed.

“Well, they left before we got there, then,” Bette said.

“Then, who told you what happened to the victim?” Pat asked them.

“Nobody,” Bette said. “We had to figure it out for ourselves. When we were removing

the victim from the car, Kathy had her hands on the girl’s head and felt the defects.

That’s the first indication we had that it was more than a traffic accident.”

“Cop Number One told me he couldn’t take information from the man at the scene because

he had to stay with the injured person,” Pat said.

“He didn’t stay with his victim,” Bette said firmly. “There was nobody there.”

“Cop Number Two said she couldn’t take information because she was busy directing

traffic.”

“There were no cops at the scene when we got there,” Bette reiterated. “No one was

directing traffic. The place was deserted. We came with lights and sirens and we almost

by-passed the scene because there was nobody there to wave us over.”

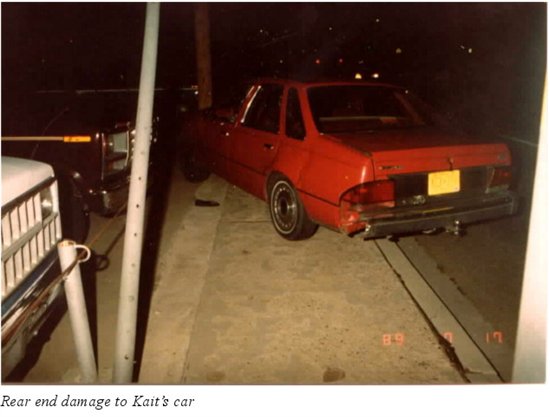

The medics then turned their attention to the scene photos.

“Is that new damage?” Kathy asked, indicating the car’s rear bumper.

“Look right there!” Bette broke in before Pat could respond. “There’s another good

six inch intrusion in the

front

bumper! The only way you’d have that much intrusion into the pole is if there was

acceleration or something pushed that car from the back.”

“I don’t understand why your names are not on the police reports,” Pat said.

“It’s probably because there was nobody there to identify us,” Bette speculated.

Pat transcribed the interviews and both women signed affidavits.

It was one more piece in a jigsaw puzzle created by a madman.

There were nights when I lay in bed, too emotionally exhausted to fall asleep, and

tried to recall what it had been like to live in an orderly world. I had once been

a woman who was seemingly blessed with everything — good health, a happy marriage,

five children, a career and a stimulating social life. If anyone had suggested that

a day might come when I would have only four children, when I couldn’t care less about

writing, when my closest friends would be private investigators, psychic detectives,

and the families of murder victims, I would have considered them insane.

Eventually such thoughts would become blurry and start running together and I would

slide into sleep, but always now it was a fitful sleep, racked by disturbing dreams.

Occasionally one of those dreams would stand out from the others in ways that made

me wonder if it was more than a dream. The colors were more vivid, the sounds and

aromas were clearer, and many times those dreams contained printed text like the

“Katie sat down and read a magazine”

message in my dream about Roxanne’s heart tattoo.

One night I dreamed that I was looking at a children’s picture book. There was an

illustration of a small car with a little slip of paper floating toward the ground

as if it had been dropped from the driver’s side window. Beneath that picture ran

a line of text—

“If only they knew about the ticket it would explain a lot to them.”

As I stared at that image, it was abruptly replaced by a picture of a parking lot

filled with cars. Near the front, there was a red Ford Tempo. Beneath that picture

the text said,

“Look for the BLUE CAR!”

In my dream I started scanning the rows of cars in search of a blue one but couldn’t

find one. Then, suddenly, a large car pulled out from behind the small red car. It

was a police car.

I awoke with my heart pounding and a strong feeling that this was indeed a message.

Psychics had told us that Kait’s car was stationery when she was shot, and the accuracy

of the shooting supported that theory. Our question had always been, what could have

caused her to stop where there was no stop sign or traffic light? My dream contained

a possible answer

— Kait would have stopped if she had been pulled over by a police car!

As a writer by trade I am practiced in creating scenes. This one comes without effort

as if it’s a video playing in my head. A police car materializes behind Kait with

its lights flashing. Kait, who is no stranger to traffic tickets, starts to slow down.

The police car then rams her car, damaging the bumper and side panel and propelling

it across the median and up onto the opposite curb. Kait sits there, trapped and terrified,

hemmed in on all sides as predators congregate around her like a pack of wolves. I

build my cast of characters, playing no favorites. An Quoc Le is at the forefront,

with Dung and Khanh Pham right behind him. Paul Apodaca is there with his brother,

Mark, and their drug dealer, Lee. Miguel Garcia and Juve Escobedo are there, accompanied

by Marty Martinez, who carefully sets his beer can down on the curb, intending to

retrieve it later. There is no record of a traffic ticket, because the driver of the

police car doesn’t issue one. The imaginary traffic violation was a pretext for stopping

Kait. This is a phantom ticket, existing only in her mind in her final moments of

consciousness.

It is Kait’s ticket to the After World.

I knew that Don and Pat would have a hard time accepting that scenario, so I didn’t

mention it. But I recorded the dream in my journal against a day when it would either

be proved or disproved.

I didn’t expect that day to come as soon as it did.

I had become accustomed to receiving e-mail from visitors to Kait’s Web page, so I

wasn’t surprised to find a message with the subject line, “Kait,” in my inbox:

I was in Albuquerque for a wedding back in 1989 and was just up the street from where

it happened. We passed by it on our way to the motel. I saw the car and Kait. I can’t

believe that this has gone unsolved this long.

May God be with you.

Carolyn

I started to respond with a routine “Thank you for caring,” and then did a double

take.

“I saw the car and Kait.”

How could this woman have seen Kait? Both Cop Number One and Cop Number Two had reported

finding Kait prone across both bucket seats with her head against the passenger door.

I sent Carolyn an e-mail asking her to describe the scene. Were there other cars there?

Were police directing traffic? Had a crowd gathered?