One to the Wolves, On the Trail of a Killer (16 page)

Read One to the Wolves, On the Trail of a Killer Online

Authors: Lois Duncan

“We have something here that we need to look into,” Pat said.

When her students regarded her blankly, she continued, “‘Susan Smith’ is the name

of the friend Kait visited on the night of the murder. Susan’s maiden name was ‘Gonzales.’

Several months after this check was written, Susan married a man named ‘Smith.’ The

bank where this check was deposited is in the town where the couple lived at that

time. It’s possible this is a coincidence. But if it isn’t, that would mean that Kait’s

new friend, who routed her down Lomas that night, received a check from people linked

to this business three years before she moved to Albuquerque. I’ve no idea what the

significance of this may be, but we need to find out whether the person who received

this check is

our

‘Susan Gonzales Smith’.”

“How do we do that?” one of the interns asked.

“We need to locate the employee who wrote the check,” Pat said. “The owner of the

shop is now deceased. Your assignment is to track down his employee-girlfriend.”

The interns set out eagerly on their mission, but the challenge was more than they

could handle. The bookkeeper had married, divorced, remarried, and divorced again,

and was listed in public records under four different names. Following her court history

of fraud, forgery, and embezzlement, the interns tracked her progress as she racked

up residences in ten towns in two different states. Then the trail ran out.

One more lead down the drain.

However, Pat was able to locate and interview Susan Smith’s best friend, the woman

Susan had trusted to forward her tax statements. That friend told Pat that she hadn’t

met Kait in person, but Susan had talked a lot about her. The friend said, according

to Susan, a few days prior to the murder, Kait had overheard Dung screaming on the

phone. She heard enough to get the gist of the conversation and had told Dung, “I

know what you guys are up to, and I don’t want to get involved.”

Dung had responded, “Too late. You’re already involved.”

“Involved in what?” Pat asked.

Susan’s friend became nervous and refused to say anything more.

In 2003, the Bernalillo County Sheriff’s Department formed its own Cold Case Unit.

The officers who came out of retirement to man the unit had impressive track records

and were actively solving old cases.

One detective, a former FBI agent, had spent forty-seven years in law enforcement.

In a newspaper interview, Bernalillo County Sheriff Darren White described him as

“no frills — 100 percent cop — a legend.”

Although the Sheriff’s Department didn’t have jurisdiction over Kait’s case, Pat,

who had met the detective socially, decided there was nothing to lose by requesting

his unofficial take on the physical evidence. He agreed to review the scene materials,

so Pat sent him the APD field and forensic reports and the scene photos.

The detective responded with his written opinion:

1) This was not a random drive-by shooting.

2) The shooting occurred

after

Kaitlyn’s vehicle struck the utility pole.

3) The accuracy of the shots suggests they were fired at a very close range at a

non-moving

target.

4) Had the shooting taken place while the victim’s car was in motion, it would have

veered to the right of the roadway due to the left-to-right camber of the pavement.

Also, the victim’s falling to the right would have turned the steering wheel in that

direction if she was grasping the steering wheel at the time of shooting.

5) Damage to the left end of the rear bumper suggests the rear of her vehicle was

struck and pushed to the right by a second vehicle

which veered her car across the median and into the utility pole.

6) This shooting was intentional and Ms. Arquette was the specific target.

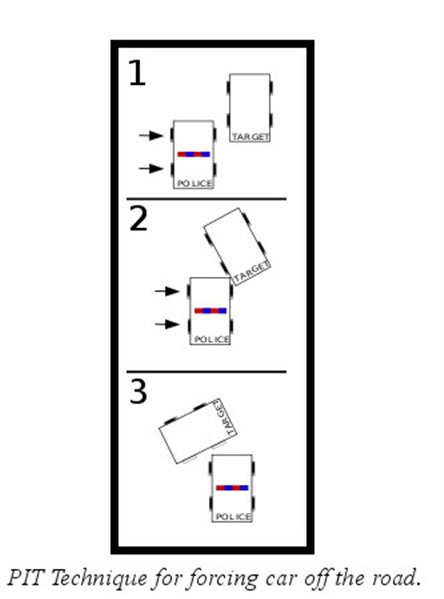

From an Internet search I learned that the method of tactical ramming described in

Point # Five is called the “PIT Technique” and is widely used by police to force a

car off the road. I was able to find a diagram that depicted the process. It meshed

precisely with the damage to Kait’s rear bumper.

This report from a highly respected member of law enforcement supported our suspicions,

but what could we do with it? The APD Cold Case Unit had disbanded, and no other agency

had the authority to follow up on this.

But one thing I did now have was an interpretation of the odd postscript that Kait

had tacked onto one of Betty’s early readings

: “Mom, I love you. Look out for the walker, the innocent walker, who does more than

walk.”

Apparently Kait had been shot by someone on foot.

By now, the families who posted their stories on our website had begun to network

among themselves, sharing information and occasionally establishing links between

what initially appeared to be unrelated cases. The families of twenty-four New Mexico

murder victims became so closely united that they held their own press conference

in Albuquerque to demand the c

reation of a New Mexico Bureau of Investigation with jurisdiction to investigate cold

cases throughout the state and to investigate any case in which there was a conflict

of interest involving the investigating agency and the victim or the suspect. The

families’ stories cited instances of alleged malfeasance involving nine New Mexico

law enforcement agencies.

Despite the fact that she’d broken a leg and was in a wheelchair, Rosemary Sherman

flew to Albuquerque from her home in California to keynote the conference. Rosemary

described her meeting with the new Sandoval County sheriff, who had promised to reopen

her son’s case. “When the sheriff pulled John’s case file to prepare for our meeting

yesterday, he discovered that the previous sheriff had shredded its contents,” she

said. “There is nothing left but a partial autopsy report.”

The press conference received extensive coverage by the media, followed by a flurry

of horrified letters to local newspapers. O

ne week later, it was as if the event never happened. It was yesterday’s news.

However, the website continued to elicit new information in regard to the top echelon

of the New Mexico drug scene:

One person wrote

: “This is in response to the psychic’s description of the house in the mountains

where Kait Arquette saw a VIP buy drugs. I know all about those homes and what they

are used for. A man I used to do business with in New Mexico got involved with a drug

cartel. He purchased a number of homes, some with airstrips. That’s how the cartel

laundered money. Some of those homes were mansions worth millions of dollars. Rarely

did anyone live in them. Occasionally they would be used for visitors of the cartel

or other drug transactions.”

So many people seemed to have first hand knowledge about VIPs who controlled the New

Mexico drug scene, yet no one was willing to speak out. And with good reason. There

was no way to know whom to trust.

Although the Real Crimes site had not yet produced any miracles, it was serving the

purpose for which it was created – bringing allegations of mishandled cases to the

attention of the public. A number of reporters and TV producers were using the site

as a resource, and an investigative Internet newspaper was running a series of articles

titled “Corruption in New Mexico.” S

everal of our cases were also subjects of books.

From the Tally Keeper’s notebook:

Update

– Nancy Grice’s daughter, Melanie McCracken:

Melanie’s case was featured on NBC Dateline, earning them the

Edward R. Murrow Award for investigative reporting.

Update

— Arry Frank’s sister, Stephane Murphey:

Thanks to on-going pressure from a reporter, the Rio Rancho Department of Public Safety

finally agreed to submit DNA evidence from under Stephane’s fingernails to

CODIS (Combined DNA Index System Program)

.

The DNA matched that of a prison inmate, David Bologh, who had been a neighbor of

Stephane’s. Bologh was arraigned on charges of murder, kidnapping, aggravated burglary,

auto theft and tampering with evidence.

Update

— Bill Houston’s daughter, Stephanie Houston:

After nearly four years, Bill and his private investigator were finally able to convince

the district attorney to reopen Stephanie’s case. A grand jury indicted her boyfriend,

Patrick Murillo, on a vehicular homicide charge.

No, the Red Sea, (or, more aptly, “The Blue Sea”), had not parted, but some waves

had been created. The voices of the twenty-four families who spoke out at the Albuquerque

press conference had been twenty-four times louder than the voice of one family alone.

In June 2004, I was invited to speak at a convention of the New Mexico Survivors of

Homicide. It was a moving experience to finally meet in person some of the families

that I had come to feel so close to through e-mail and phone conversations.

Following my opening talk, a panel of judges entertained questions from the audience.

As I studied the names in the program, I realized there had been a substitution. The

Chief Judge of the judicial district that covered all of Bernalillo County was missing

from the line-up.

“Where’s the star of the panel?” I whispered to the woman seated next to me.

She turned to regard me with surprise. “You mean you haven’t heard?”

“Heard what?” I asked.

“He’s been arrested. He and a lady friend were stopped when they tried to avoid a

DWI checkpoint. They’d apparently come from a party. The judge had cocaine on the

crotch of his pants and a bindle of it in his lap. He’s been charged with drug possession

and tampering with evidence.”

“Where was the party?” I asked.

“Who cares?” the woman said. “He was out with his friends snorting coke. Isn’t that

enough?”

No, it’s not enough,

I thought, although I didn’t say it aloud. If this renowned judge was doing drugs

at a party, there must have been other well-connected people in attendance.

I leaned forward and tapped the shoulder of a reporter in the row in front of me.

“Who does the judge who got arrested hang out with?” I asked her.

“There’s a clique,” she told me. “It’s tight and goes back a long way. Politicians

and well known business people.” She paused and, then, as she realized where our conversation

was headed, added hastily, “Of course, he has other friends too. He’s a popular man.”

There were immediate calls for the judge’s removal from the bench. After issuing a

statement of apology to his family and the public, he was whisked away to the Betty

Ford Clinic in California. Protesters lined up outside the courthouse, furious that

the judge remained eligible for retirement benefits because he’d submitted his resignation

before he could be suspended. One outraged woman stood sweltering in the 95 degree

heat, waving a sign that read, “Who’s your dealer, Judge?”

Legislators expressed their concern that “one sad, isolated incident” might undermine

the integrity of the System in the eyes of the public.

But, as it turned out, it was not one isolated incident.

Several days after the judge’s arrest, an investigative reporter exploded a TV news

story that revealed that the judge had a lengthy history of using illegal drugs. The

story was based upon information in a long-buried narcotics report that alleged that

the judge’s cocaine use had been known to law enforcement for at least eight years,

along with the names of other socially prominent drug users.

The judge’s name appeared four times in the forty-eight-page report, which documented

a Department of Public Safety investigation to pinpoint participants in New Mexico’s

multi-million dollar drug trafficking business.

Bernalillo County Sheriff Darren White, who had been the DPS secretary at the time

the report was written, denied knowing anything about it.

The TV station stood by their story.

As the conflict continued, more information surfaced. The report had, indeed, been

prepared by a DPS agent, who was assigned as the state’s representative to an Organized

Crime and Drug Enforcement Task Force. The document detailed drug smuggling and money

laundering in New Mexico that spanned twenty years, along with a list of participants

that — according to the privileged few who had seen the report—read like a “Who’s

Who” of the New Mexico drug underworld, with judges, lawyers, politicians, sports

celebrities and prominent businessmen listed right alongside the state’s narcotics

kingpins.

Because no charges had been brought against any of those people, their names could

not be released.

The Judicial Standards Commission obtained a copy of the report, and David Iglesias,

US Attorney for New Mexico, was interviewed on television.

Reporter:

Important document?

Iglesias:

Absolutely!

Reporter:

Eye opener?

Iglesias:

A page-turner. I couldn’t put it down.

Governor Bill Richardson asked the state Judicial Standards Commission to initiate

an investigation.

The judge’s attorney was adamantly against such a probe.

“That’s the kind of crap that can ruin people’s lives,” he said.

People’s lives have already been ruined!

I longed to scream at him. The drug activities of the people on that VIP list dated

back to before Kait’s murder. A limousine driver told investigators that, in the 1980s,

he transported the judge and two prominent attorneys to Santa Fe to meet with legislators

at a bar, and the judge and his associates used cocaine throughout the trip. It stood

to reason that the legislators they were planning to spend the evening with would

have been involved in the same activity.

Who were they?

Three psychics, from different areas of the country, had given almost identical responses

to our question, “Who was the VIP Kait saw involved in a drug transaction?” Those

descriptions formed a thumbnail sketch that I thought I might recognize if I could

compare it to names of the people in the narcotics report.

10

I did everything I could to get a list of the names, but even my reporter friends

couldn’t get access to them. Unless the VIPs were careless enough to be caught with

cocaine in their crotches their identities would forever be protected.

When the (now former) judge returned from rehab, he pleaded guilty to DWI and possession

of cocaine. He was sentenced to a year’s probation and two days of house arrest and

given a conditional discharge on the drug charge, so the felony conviction would eventually

be removed from his record. His lady friend also pleaded guilty and received the same

“punishment.” By entering guilty pleas, they avoided trial, which meant they never

would be forced to disclose where they had been that night or identify their drug

suppliers.

Years were passing, and Don and I were growing old. We kept ourselves busy adding

cases to the ever-expanding Real Crimes site and doing volunteer work. We had developed

a casual social life on the Outer Banks, but we missed the longtime friendships we’d

enjoyed in New Mexico. Most of all, we missed our children. With the loss of Kait,

the family unit had fragmented, and our surviving children were scattered all over

the country. We visited them, of course, and they visited each other, but the solid

structure of “Family” no longer existed and our lives felt empty without it.

Then, one day, when I was feeling particularly downhearted, Pat called with some up-lifting

news.

“Remember the detective with the Bernalillo County Cold Case Squad, who was convinced

Kait was forced off the road and then shot?” she said. “Well, I ran into him and his

wife last night at a barbecue, and he told me he’s submitted his findings to the APD

Cold Case Unit.”

“I thought that unit had folded!” I exclaimed in surprise.

“It had, but it’s now been resurrected,” Pat told me. “The new lead detective is said

to be honest and dedicated. This could be the break we’ve been praying for!”

The

Albuquerque Tribune

ran a lengthy article about the new APD Cold Case Unit, stating that the lead detective

was “the first Albuquerque Police Department agent to take seriously the reams of

information acquired by the family in the Kaitlyn Arquette case.”

“I believe the evidence is strong, very strong,” the detective was quoted as saying.

“The family’s private investigator and I have agreed to sit down together. There’s

so much more we can do now that we couldn’t years ago. That’s what’s really going

to solve these cases— forensic science.”

When Pat met with the detective she was favorably impressed. She described him as

friendly and accessible and interested in reviewing her information as long as it

didn’t implicate the Vietnamese.

“The homicide detectives have assured him they thoroughly investigated the Vietnamese

angle and there’s nothing to it,” Pat said. “They’ve told him your book is fiction,

so he won’t even read it. I assured him I’m not convinced that the Vietnamese killed

Kait. They’re a bunch of crooks and I feel sure they were somehow connected, but I’m

thinking now that somebody else did the shooting.”

“Maybe so,” I conceded. “But Dung or his friends must have been there. How else could

he have known about it three hours before he was told?”

“The detective said the case can’t be prosecuted, no matter how strong the evidence,

because the statute of limitations has run out,” Pat said. “I told him the most important

thing is to uncover the truth so the family can have closure.”

“I thought there was no statute of limitations on murder!”

“That’s true today, but not in 1989,” Pat said. “Back then, the statute of limitations

on murder in New Mexico was fifteen years. That law has since been changed, but the

detective tells me it’s not retroactive.”

“You mean, if somebody came forward tomorrow and confessed to the murder, he wouldn’t

be charged?” I asked incredulously.

“Probably not,” Pat said.

When the story about the detective’s willingness to work on Kait’s case appeared

in the paper, we received an anonymous e-mail that contained a veiled threat to other

members of our family. Then we began to be told things that seemed deliberately designed

to send us off on tangents. Members of law enforcement seemed suddenly to be confiding

inside information about Kait’s case to everybody they met, and those people were

helpfully passing those statements on to us: (1) Kait had been having an affair with

Cop Number One and he killed her because she was becoming too possessive; (2) Kait

was an APD snitch and was killed in a drug sting; (3) Kait was shot as a message to

me that people didn’t like my books; (4) and, of course, the old standby— Kait was

the victim of a car-jacking.

We didn’t believe any of those statements, yet we couldn’t arbitrarily dismiss them

on the very slim chance that one might actually be accurate. So hours of our time

and Pat’s were spent checking out leads, all of which proved to be dead ends.

Pat continued to meet with the detective, but their conferences were turning out to

be less productive than we’d hoped.

“He has total faith in the homicide department,” Pat told us. “He acknowledges there

were some problems with the investigation, but he’s certain those weren’t intentional.”

“What does he have to say about the fact that no one was there when the ambulance

arrived?”

“Police reports don’t support that, so he doesn’t believe it.”

“But the police reports are filled with misinformation!”

“He doesn’t think that way, and that’s understandable. His launching pad is the information

in the case file. If he questions that, he’ll have no foundation to build on. He’s

not out to reinvent the wheel, just to keep it rolling. Homicide detectives have assured

him the Hispanic suspects killed Kait, so his goal is to get information to support

that scenario.”

The detective then received a startling new lead. An alleged eyewitness had resurfaced

with information that could nail Miguel Garcia. The detective would not tell Pat the

identity of this witness, but he did reveal that she was female and said he was working

hard to gain her confidence.