One to the Wolves, On the Trail of a Killer (12 page)

Read One to the Wolves, On the Trail of a Killer Online

Authors: Lois Duncan

Reading that letter and visualizing Kippy’s poor mother, I was violently sick to my

stomach.

Soon after that, I experienced that same reaction when Paul Apodaca suddenly hit the

headlines:

Albuquerque Journal, October 5, 1995

MAN RAPES STEPSISTER TO GET INTO PRISON

An Albuquerque man told the judge he raped his 14-year-old stepsister so he could

go to prison to protect a younger brother imprisoned on a murder conviction. Judge

Richard Knowles obliged with a 20-year sentence for Paul Raymond Apodaca, but recommended

to the Department of Corrections that Apodaca not be housed in the same prison as

his brother.”

By now Pat had interviewed the first two officers at Kait’s scene. Their statements

conflicted so radically that they might have been at two different crime scenes. Each

blamed the other for not taking information from Apodaca. Cop Number One said he assigned

that job to Cop Number Two, because, “I had to make a choice — I had to stay with

the injured person.” Cop Number Two was adamant that Cop Number One had specifically

told her

not

to take information from Apodaca, because he already had done so. Cop Number Two

told Pat that, as soon as she suspected murder, she called her supervisor. Yet the

supervisor recalled no call from Cop Number Two and said the person who called her

was Cop Number One.

Pat went down to the detention center to get Apodaca’s version of the story.

“The first thing he asked was, ‘How did you find me?’” she told us. “He apparently

thought the police reports had made him untraceable.”

When she questioned him about his presence at the scene, he explained he was in the

neighborhood to buy drugs from a friend named Lee. He described how he and Cop Number

One had gone together to look into Kait’s car, but denied ever seeing Cop Number Two,

although Cop Number Two had told Pat that she was with the two men when they went

to Kait’s car and had described Apodaca’s excitement at the sight of so much blood.

Apodaca went on to say he had given Cop Number One his name and then driven off in

his car — a VW bug — and gone around the corner to his drug dealer’s house. According

to Apodaca, he remained with Lee for about half an hour, and when he left he noticed

an ambulance at the scene.

Pat recognized Lee’s name from a public records report of Apodaca’s 1990 arrest for

shooting a prostitute from his VW bug. At the time of that incident, Apodaca had presented

Lee’s MVD identification card, apparently assuming that Lee would be immune to arrest.

Pat went to Lee’s home, and his mother answered the door and said Lee was sleeping.

When Pat identified herself as a private investigator who was working on the Arquette

case, the woman responded, “You mean the girl who was shot by those Vietnamese guys?”

Lee’s mother confirmed that Paul Apodaca was a close friend of Lee’s and promised

to give Lee Pat’s card.

She also proudly volunteered the fact that her other son was an APD narcotics officer.

Highlights of 1996:

Jim Ellis retired.

Michael Bush and his wife became parents of a little boy.

Pat Caristo became the grandmother of a little girl.

Don began doing volunteer work for Habitat for Humanity.

Kerry wrote her first book and won the Colorado Young Readers Award.

Both Robin and Brett got married.

Donnie won $11,000 playing a slot machine on an Indian reservation.

As for me — I dreamed.

What I dreamed about was Kait’s diary.

During daylight hours I obsessed about that diary. With Lawrence now out of the picture,

I would never know if Kait’s journal actually existed. Despite the fact that the man

was a sadistic con artist, his information about Kait’s personal life had been disturbingly

accurate. He had known that, at age sixteen, she had posted an ad in a singles magazine

and misrepresented her age by three years. That was not a specific you pulled out

of a hat. If Lawrence himself was a fraud, then he had to have obtained information

from somebody who knew Kait.

Either that, or his conspirator had access to her diary.

One night before falling asleep, I said to Kait, “I’m going to sleep with my mind

propped open. I want you to try to get into it and tell me what’s in that diary. If

there isn’t any diary, then tell me what you would have written in a diary if you’d

kept one.”

That night I had a vivid dream in which Kait appeared, shaken and teary-eyed, and

announced that she had been raped. Then, suddenly I was reading an account of that

rape in a journal. The entry was worded in third person, as if the author was trying

to distance herself from the violence, and it ended with the sentence, “Then Katie

sat down and read a magazine.” At the bottom of the page there was a little stick-on

heart like the ones our grandchildren liked to paste on envelopes. In the dream I

reached out and touched the heart, and it came off in my hand. I turned it over, and

on the back there was the name “Roxanne.”

I woke up with a start and lay, staring into the darkness, trying to discern the meaning

of this extraordinary message— if, indeed, it was a message. We had no reason to believe

that Kait had been sexually assaulted, and I wasn’t aware of any friend of hers named

Roxanne. Kait had been an avid reader when it came to novels, but the only place she

read magazines was under the hair dryer.

Kait’s purse had been returned to us by the hospital and contained a date book with

a page in the back for phone numbers. I kept that book in the bottom drawer of my

dresser. Now, I got out of bed and groped in the drawer for the book, which I carried

into the bathroom so I could turn on the light and read without waking Don. The calendar

revealed that, on the week of her death, Kait had had not one, but two, appointments

with her hairdresser, one for a haircut and the other for

“pictures with Roxanne.”

I flipped to the back of the book and found the number for the beauty parlor. In the

morning I dialed it and asked to speak to “Roxanne.” The receptionist told me that

nobody named Roxanne was employed there. Then a voice in the background called out,

“There was a Roxanne who used to work here. I think she quit to start her own shop.”

I asked what Roxanne’s last name was, but nobody could remember.

I phoned Pat and told her about the heart dream.

“I think Kait wants us to talk to her hairdresser,” I said.

Pat was kind enough not to scoff, but she wasn’t exactly jumping up and down with

excitement.

“You don’t know where Roxanne works or what her last name is?”

“No,” I said. “But I do think we need to find her.”

“I’ll see what I can do,” Pat said without much enthusiasm.

Several days later, she called me, sounding stunned.

“I found Roxanne,” she said. “You’re not going to believe this! Roxanne has a

heart tattoo

on her upper arm!”

Roxanne told Pat that she had been more than Kait’s hairdresser, the two had been

personal friends. Kait had babysat for Roxanne’s children, and Roxanne had used Kait

for a hair model, which accounted for the notation

“pictures with Roxanne.”

And, not only had Roxanne cut Kait’s hair, she also had cut Dung’s hair.

“I asked her if she had a problem understanding Dung’s English, since that’s the reason

the police gave for not being able to properly question him,” Pat said. “Roxanne said

she understood him fine, except on the night Kait was shot. She said he phoned her

a little before midnight, babbling, ‘Kait’s dead! They shot Kait!’ He was so hysterical

that she had to keep asking him to repeat himself.”

“He called her

before midnight?

” I exclaimed. “But he wasn’t told about the shooting until three the next morning!

Is she certain about the time?”

“Her husband’s confirmed it. They’d just watched the evening news and were getting

ready for bed. If that’s true, it means Dung knew about the shooting three hours before

police informed him. And it sounds like he knows who did it. He didn’t say, ‘Kait’s

been shot,’ he said, ‘They shot Kait!’

“Roxanne also knew about the car wreck scam,” Pat continued. “She said Kait was very

upset about Dung’s activities and wanted out of the relationship. Kait also told her

that Dung’s group was stealing cars and changing the engine numbers, which would certainly

be a reason for them to frequent that body shop. Roxanne said she tried to give that

information to Detective Gallegos, but he told her she wasn’t telling him anything

he didn’t already know.”

“Is Roxanne willing to sign an affidavit?”

“She’s eager to do that. She’s always wondered why the police wouldn’t take a statement

from her. Oh, and one other thing — I just had a call from a woman named Linda, whose

son, Nathan Romero, was murdered in Albuquerque in 1993. Linda thinks his case may

link to Kait’s.”

She gave me Linda’s number, and I immediately dialed it.

“Nathan was chased down by three cars, stabbed, and left to die in the street,” Linda

told me. “He was found with a Vietnamese medallion clutched in his hand, apparently

snatched from his killer during the struggle. APD didn’t bother to place that medallion

into evidence. It was turned over to me along with Nathan’s personal effects.”

Friends who had been with Nathan had identified his killers, but the police had refused

to arrest them.

“That Asian gang harassed me for years,” Linda said. “The men were so cocky they’d

park in front of my house and sit there grinning. They’d laugh at Nathan’s friends

and ask them if they wanted to be killed next. Even when two gang members came forward

as witnesses, APD didn’t make arrests. During one phone conversation, a police captain

got so furious with me that he bellowed at the top of his lungs, ‘We know who killed

your son just like we know who killed Kait Arquette! This is police business — butt

out!’ When I asked him why he was connecting those two cases, he yelled at me to keep

my mouth shut and forget I ever heard that.”

Linda refused to be intimidated and informed her private investigator, who contacted

the mayor and warned him that the City could expect a massive law suit if the police

didn’t do their job.

“Then things started to happen,” Linda told me. “The case detective, Steve Gallegos

— wasn’t he your case detective too? — got transferred out of the department, and

Nathan’s killers were arrested. Not that it did much good, because they plea bargained.”

When I asked Linda the name of the APD captain who had linked our children’s cases,

it turned out to be the same captain who had stated on “Good Morning, America” in

regard to Kait’s case, “The Vietnamese angle was extensively looked into. We could

find no tie to the homicide with any Vietnamese gang.”

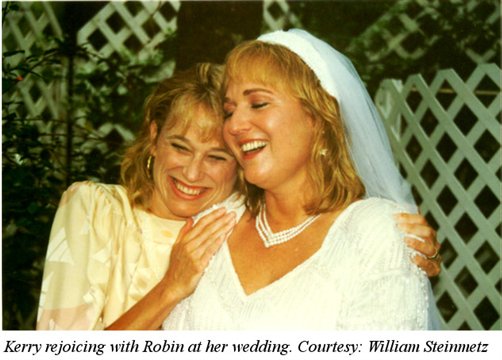

Meanwhile, our family was experiencing happy times also, for in the course of two

months we had acquired a daughter-in-law and a second son-in-law. Brett and his girlfriend

Cindy eloped to Las Vegas, while Robin was married to Anatole in a small but joyous

ceremony in a garden in Florida. We were worried about the weather because it had

been raining off and on all day, but when the bride stepped under the arbor, radiant

with happiness and more beautiful than we ever had seen her, the sun broke through

the clouds and the sky was split by a rainbow. Kerry, who was matron-of-honor, stood

slightly apart from her sister to acknowledge the space where Kait would have stood

if she had been there. When I looked at that space I was almost able to convince myself

that — for just an instant — it was occupied by the misty form of a girl in a peach

color dress the same shade as Kerry’s. Then the image was gone, and I accepted it

as a trick of the light and an overactive imagination.

That evening, after the newlyweds left on their honeymoon, the rest of us reminisced

about happy times and sad ones. Kait was very much on our minds.

“Since the cops don’t want your information, why don’t we put it on the Internet?”

Brett suggested. “Maybe somebody out there will read and react to it.”

Brett, who was a computer guru, designed the website, which included a message board

and e-mail envelope for informants.

8

He posted the page, and surfers found it. Steve Schiff, United States Congressman

from New Mexico, called to suggest that we request an Internal Affairs investigation.

I told him we had little confidence in the APD Internal Affairs Unit, since a former

supervisor — an alleged field officer at Kait’s scene — had been charged with burglarizing

a liquor store.

“Good point,” Schiff acknowledged. “Let’s try to go over their heads then.” He wrote

a letter to Attorney General Janet Reno, requesting that the Justice Department look

into a possible police cover-up. The Civil Rights Division responded that the federal

five-year statute of limitations prohibited their doing that.

“I’m sorry I couldn’t do more for you,” Congressman Schiff told us. “I do have one

suggestion. Under New Mexico law, the State Attorney General can prosecute a case

where the local district attorney declines. As the DA has not charged the individual

you suspect, I recommend you contact the AG’s office.”

It was a well-meant suggestion from a good and caring man, who didn’t realize that

the Attorney General wouldn’t meet with us. And even if Congressman Schiff could convince

him to do so, whom would we accuse of Kait’s murder? Dung Nguyen? An Quoc Le? Bao

Tran? Paul Apodaca? A hired hit man who might or might not have been Miguel Garcia?

As private citizens, neither we nor Pat had the authority to force witnesses and suspects

to talk to us. Only the police could do that.

The traffic at Kait’s website continued to accelerate, and many of those visitors

contacted us by e-mail. Among them were a forensic expert from Illinois and a crime

scene technician from Michigan, both of whom offered to review Kait’s scene information.

They asked us to send them copies of the scene reports, autopsy report, and a full

set of crime scene photos.

We were able to provide them with everything except the pictures and set out to get

those by submitting an Inspection of Public Records Act request. The APD photo lab

told us that nine rolls of pictures had been taken but only a couple of shots on each

roll had turned out. We ordered two sets of the twenty-two photos. The charge for

those snapshot size prints was $176.

I was not prepared for the impact those photos would have on me. Although Kait was

not in the pictures, her blood was sloshed on the seat and floorboards of the car.

There was a large pool of body liquids on the curb next to the passenger’s door, and

a small black object that looked like a shoe lay on the ground outside the closed

door on the driver’s side.

I opened the packet while standing at the mailbox and trudged up the driveway to the

house, clutching the photos to my chest. Since Don was not home, and I had to reach

out to somebody, I e-mailed the technician in Michigan.

He responded instantly: “Lois, Lois, Lois, it’s a grim business, this. It’s not for

anyone who ever loved the victim. We hope the pictures tell a story, but it’s probably

not a story you should have to read or can read. It’s told in the language of blood

and broken glass and bullet holes. Put those pictures away for now. I’ll let you know

my reaction when I receive my set.”