One to the Wolves, On the Trail of a Killer (13 page)

Read One to the Wolves, On the Trail of a Killer Online

Authors: Lois Duncan

I went into the bedroom and buried my face in a pillow and screamed until the back

of my throat felt like I’d swallowed lye. Because I

could

read the language of broken glass and bullet holes, not with the mind of a criminalistics

expert, but with the heart of a mother. I could see my daughter in that car, gripping

the steering wheel, frozen with horror as a bullet crashed into the door frame next

to her head, and there was no place to run, no place to hide, and Mother and Daddy

just a few miles away in that big safe house, and no way to reach them. If only I

had been with her! In my mind I rewrote the story so I was seated beside her and could

grab that shiny gold head and yank it down below window level. In that vision I threw

myself across her and leaned on the horn. People came rushing to windows, came pouring

out of buildings, came racing to save this terrified girl, who by now I had somehow

managed to shove down to the floor boards. When the other shots came — (

if

they came, for perhaps the killers would be frightened off by the commotion) — I

would be the one to receive them. And, oh, I would receive them gladly! I would smile

as I slid into darkness knowing that Kait would survive to go to college, to become

a doctor, to meet and marry Prince Charming, to have children just as ornery and strong-willed

and naughty and wonderful as she was, and to live and live and live.

“I want her back!” I shrieked into the muffling mound of the pillow. “I want her back!”

Then finally I cried.

Eventually I must have fallen asleep from exhaustion, because the next thing I knew

I was sprawled on the bed in a room that was gentled by twilight, and the sound of

the TV in the living room told me that Don had returned and was watching the 6:00

p.m. news.

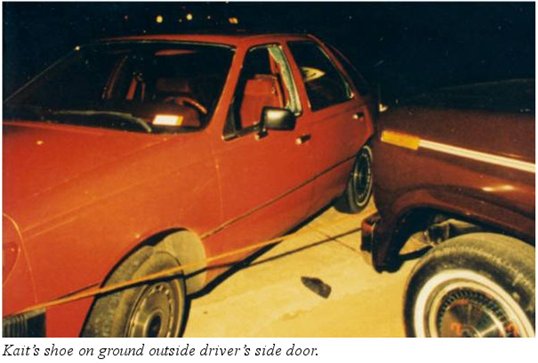

I sat up and turned on the light and spread out the photos on the bed. The object

on the ground was, indeed, Kait’s shoe. Since the first two officers at the scene

had stated that they had gone to the passenger’s side, I wondered if the killer might

have opened the driver’s door to check and make sure she was done for.

If so, it was possible that either he — or Paul Apodaca, if Paul wasn’t the killer

himself — had cleaned out her purse. That purse had been returned to us at the hospital,

and when I opened Kait’s wallet I’d been surprised that it contained no money. I knew

that Kait had had cash when she’d left our house that night, because she had mentioned

her plan to buy ice cream to take to Susan’s. Susan had said Kait didn’t arrive with

ice cream.

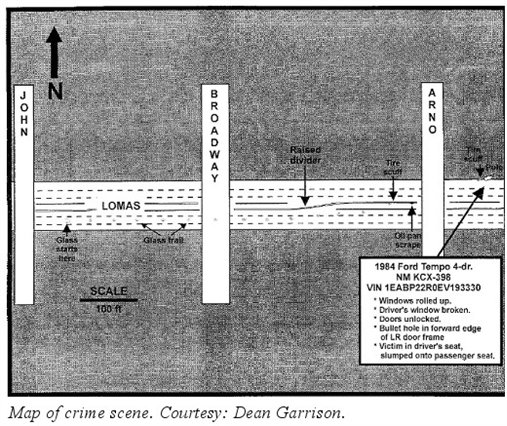

We mailed the reconstructionists copies of the photos, and both were puzzled by their

limited number and poor quality.

“Are you saying that they were not able to take more than twenty-two pictures out

of all those exposures?” asked the cop in Illinois. “Where are the shots of the large

concentration of glass that was used to determine the spot where the shots were fired?

If auto glass found at the scene was considered important enough to measure and describe,

there should be photographs of it along with evidence markers.”

Our consultants were also frustrated by the fact that there were no well-lighted,

close-up, scale photos of Kait’s car.

“There ought to be photos that include a scale or ruler and are labeled with markers,”

they told us. “Once the scene work was completed, the car would have been removed

to a secure location for a detailed search, latent print processing, and photography.

There should be at least one roll of film showing that process.”

We contacted APD and were told there were no daylight photos, no pictures with scale

markers, and no pictures of the pile of glass. No photos existed other than the ones

we’d been given.

Then, something happened to convince us that wasn’t the truth.

The crime scene analysts had asked to see televised news footage, so one evening,

while I was fixing dinner, Don set out to make copies of our videos of TV coverage.

Suddenly he shouted, “Come see what I’ve found on

Sightings

!”

I rushed in from the kitchen, and he backed up the tape and re-ran it. An image flashed

onto the screen and immediately vanished. It was there for only an instant, but that

was long enough.

“That’s Kait’s car!” I exclaimed. “And the photo was taken in

daylight!”

“Hang on,” Don told me. “There’s a better image coming up.”

There it was — another daylight APD photo of Kait’s car that zeroed in on a close-up

of the bullet hole in the doorframe. That hole had a piece of evidence tape positioned

above it, which did not appear in the photos that we had been given.

We sent the video to the crime scene technician in Michigan, who scanned the frames

and transferred them to discs. Neither of our consultants was able to tell much from

the grainy images.

“What these do reveal, however, is that APD has been holding out on you,” one told

us. “Keep asking for copies of the photos. I’m sure there are people in APD who refer

to you as ‘that nutty Arquette woman,’ but somewhere you may run into someone who

sees this as a noble search for the truth.”

Don submitted a second request, asking for all the case photos that had not been provided

to us. The supervisor of the photo lab responded that there now appeared to be only

four rolls of negatives in Kait’s file, as compared to the nine rolls that had been

there previously.

“I don’t understand what’s going on,” she commented. “We don’t have the things we

ought to have.”

She had those eighty photos printed for us. All turned out to be night scenes and

none showed the broken glass or evidence markers. Don reiterated that our request

was for

all

photos taken by APD of the crime scene and of Kait’s car, including the daylight

images with the evidence tape.

The lab relayed that request to the legal department and was told to inform us case

photos were not public record. Then, one hundred and twenty-six more photos mysteriously

surfaced. None had been taken in daylight and none showed the glass.

The new batch of photos contained shots of Kait in the hospital. As I gazed at the

bloated face that had once been so beautiful and at the poor shaven head encased in

bloody bandages, I recalled Bob Schwartz’s statement about his view of reality.

“A prosecutor’s reality is not defined by truth,” he had told me. “It’s a refined

and screened and artificial version of it.”

There was nothing refined about the content of these photographs. I ran my finger

across Kait’s shattered temple and traced the curve of the ravished cheek, as if by

touch I could magically make them whole again.

These were

my

reality.

The fact that police had taken daylight pictures of Kait’s car, revealing evidence

tape that wasn’t in any of the scene photos, indicated a second day work-up that wasn’t

on record.

The Criminalistics Supervisor in charge of Kait’s scene was no longer with APD and

now lived out of state. He told Pat on the phone that he had not seen any pile of

glass and thought the “trail of glass” referred to in scene reports might just have

been fragments and could not even have been determined to have come from a particular

vehicle. He had no explanation for the “No Evidence Hold” note in the case file and

acknowledged that there

had

been a second day work-up. He said reports of that work-up had been sent to the case

detectives and to the records department. He didn’t recall that his team had found

anything significant or taken any photographs.

But the picture with the evidence marker indicated that they

had

taken photos, whether the supervisor remembered that or not. And a homicide detective

had confided to Robin’s girlfriend Maritza that the location of a bullet found “later,

not during the initial investigation,” had proved that the shooting was a “hit.”

Was it possible that Criminalistics had found more than a fragment of the bullet that

penetrated the doorframe, and that bullet was of a larger caliber than the bullets

that fragmented in Kait’s head? Since the investigative units appeared to be compartmentalized,

it was probable that Criminalistics would not have been aware of the findings of the

medical examiner. But the detectives in the homicide department, who were coordinating

information and picking and choosing which reports to place in Kait’s case file, would

have been acutely aware of what they were looking at if evidence indicated those bullets

were different sizes. Two individuals, firing different caliber weapons, could not

be considered “random shooters.”

And what about the “large accumulation of broken glass” that suddenly now had become

undistinguishable fragments that might not even have come from Kait’s car?

“Maybe there

was

no glass in the street,” Don speculated. “Perhaps Kait was

not

shot at that junction.”

9

Our only hope of obtaining the rest of the photographs seemed to be to file a suit

against the police department. So we made another trip to Albuquerque to meet with

attorneys to see what our legal options were. We were up front about the fact that

our goal was to take the case to court so we could subpoena copies of the case materials.

One attorney after another told us they weren’t interested.

The last one we met with was compassionate enough to tell us why.

“No attorney will take on this case with that stipulation,” he said. “True, there

are those of us who have built our practices on suing the police, but we always settle

out of court with no admission of wrongdoing. That’s the way it’s done here.”

Once again, we submitted a request for the return of the materials from Kait’s desk.

This time we channeled that request through the APD Legal Department, who sent a legal

assistant to the evidence room. She found, as Pat had done, that Kait’s things weren’t

there. However, she continued to investigate and eventually discovered a closet safe

in the Violent Crimes Unit which contained all the “lost” materials from Kait’s desk.

Pat insisted on being there when the safe was opened and attempted to reclaim Kait’s

personal belongings for us. She was thwarted by Detective Gallegos, who belatedly

had everything placed into evidence.

So many questions screamed for answers, but there was one that could never be answered

by posting it on the Internet. It was the source of my dream about a heart named “Roxanne.”

Where had that image come from?

Much as I wanted to accept the dream as proof that consciousness continues after death

and that those who pass over retain the ability to communicate with loved ones, my

skeptical nature was my enemy. A nagging voice in the back of my mind kept telling

me it was far more likely that at some point Kait had mentioned to me that her hairdresser

had a heart tattoo. The fact that I didn’t recall such a conversation didn’t mean

that it hadn’t taken place and the memory had been stored in my subconscious. Having

that memory surface in a dream and lead us to valuable information could have been

mere coincidence.

I phoned Roxanne to thank her for telling Pat about Dung’s phone call.

“I hope that it helps,” Roxanne said. “Kait didn’t deserve what happened to her. She

told me about the staged car wreck. Dung didn’t tell her about it until after he’d

done it.”

“You mean Kait wasn’t in on it?” I felt as if a weight had been lifted from my heart.

“Definitely not,” Roxanne assured me. “They had a big fight about it. She agreed to

give Dung one more chance to shape up and get a real job and break with those awful

friends of his. Like I told Detective Gallegos, I don’t believe Dung killed Kait,

but I’m certain he knows who did.”

“Did Pat Caristo tell you about my dream?” I asked her.

“That’s so bizarre!” Roxanne exclaimed. “And what’s even weirder is that I’d only

just gotten that tattoo. I’d had it about a week when Pat came to see me.”

That revelation was so startling that it took me a moment to absorb it. Not only could

Kait not have told me about Roxanne’s tattoo, that knowledge had not been in her memory

bank when she died. For those who sought proof that those who die have on-going knowledge

about events that occur on this earth plane after they’ve left it, that dream message

would seem to provide that.

Meanwhile, the hits on Kait’s website were rapidly increasing. My fellow writers were

among the most frequent visitors, as the Mystery Writers of America had announced

the URL in their newsletter.

Alec West, a writer in Washington State, became so incensed by the situation that

he sent an impassioned e-mail to an assortment of New Mexico politicians.

“I am flabbergasted that the State of New Mexico hasn’t stepped in officially to put

this crime scandal to rest,” he said.

No one responded.

Alec was not a man to take rejection lightly and contacted us for permission to organize

a writers’ e-mail campaign to bombard New Mexico officials with letters demanding

that APD either reopen Kait’s case or allow an outside agency to take over.

We gratefully accepted his offer, and Alec plunged into the project with vigor. He

suggested that we choose a symbolic day for this effort, such as Christmas, so people

could “give Kait a present.”

The image of Roxanne’s heart leapt into my mind.

“I’d like it to be Valentine’s Day,” I said.

Alec set up a website that would allow participants to click on Kait’s picture to

send one message simultaneously to a number of public officials and to the media,

with copies to Alec and us. We decided that the ideal time for the mailing would be

February 13, after the politician/media types left their offices for the day. That

way the mailings would filter in overnight, and when the recipients arrived at work

on Valentine’s Day they would be greeted by overflowing mailboxes.

With Alec handling the technical aspects of this venture, I devoted my own time to

posting e-mail to writers around the country, inviting them to visit Kait’s website

and, if they felt comfortable doing so, participate in the campaign.

The day of February 13 seemed eighty hours long. As we inched our way through the

final countdown, I was beset with the same sort of panic I used to feel when I gave

one of our children a birthday party and none of the mothers bothered to RSVP. In

effect, we were throwing a party for Kait, and I didn’t think I could bear it if nobody

came.

At precisely 6:00 p.m., Alec activated the website, and the floodgate flew open.

The first letter through set the mode for those that followed:

“A terrible crime has been committed in Albuquerque. The crime is not the murder of

Kait Arquette, but the inadequate i.e. bungled job that the Albuquerque Police Department

made of the investigation. It was criminal. As is necessary when crime is carried

out, call in the troops — in this case, the FEDS!!!

It’s time to police the police!!!”

We stayed up most of the night reading one supportive message after another, laughing

and crying and cheering. Occasionally a familiar name would pop up to identify a known

member of Kait’s Army, but in general the letters were from strangers. The bottom

line message was summed up in a one sentence e-mail from the editor of

Mysterious Galaxy

: “If Kait Arquette’s concerned parents were able to gather the amount of information

they have, surely the proper professionals can apply themselves to bringing her killers

to justice.”

The outpouring was so overwhelming that Alec was forced to close down the site before

noon in response to complaints from recipients with overloaded servers. “What the

hell are 5,000 God damned letters doing in my mail box?” one of them exploded.

The media latched onto the story with enthusiasm. An Associated Press article with

the headline “E-MAIL CRUSADERS WANT TEEN’S MURDER SOLVED” began with the sentence,

“It may seem like a strange plot twist — mystery writers banding together in cyberspace

to pressure New Mexico officials to solve the murder of a teenager,” and went on to

describe Kait’s website, “which questions the police investigation, accusing officers

of failing to question important witnesses.” APD responded to that with a statement

that the department believed its investigation was complete.

The only person on the hit list who was willing to be interviewed was Department of

Public Safety Secretary Darren White. “I have nothing but the utmost confidence in

the homicide unit of the Albuquerque Police Department,” said White, a former Albuquerque

police sergeant.

By now killings by police officers in Albuquerque had reached such an all time high

that the City Council commissioned an independent study “in the context of a serious

and ongoing community crisis.” The report confirmed that oversight mechanisms for

the police department were not working.

“The number of shootings is extraordinarily high for a department of its size,” one

of the authors of the report told city councilors. He also disclosed the fact that

the city set aside $4 million per year to settle claims against APD.

Since the largest portion of those settlements went to attorneys, it was easy to see

why they might be reluctant to upset that lucrative apple cart.

Although the Valentine’s Day campaign had no effect upon the people for whom it was

intended, it did yank Kait’s murder back into the public eye.

Inside Edition

filmed a segment about the case which included an interview with former DA, Bob Schwartz.

“I would categorize the police investigation as competent and thorough,” he said,

apparently forgetting his taped statement to me that the APD investigation was “sloppy

and unskilled.”

When the segment aired, Lieutenant Richard Tarango of the APD Violent Crimes Unit

issued a statement to the media that APD’s investigation had been solid.

“Nobody the Arquettes has brought to us has shown us a shred of evidence,” he told

reporters. “They have brought us

nothing

.”

That statement triggered a barrage of letters to the editor. Among those was one from

Kait’s therapist, saying, “I contacted the APD within days of Kait’s murder and spoke

to Detective Steven Gallegos. I reported information that seemed pertinent to her

death. He declined to interview me.”

Another outraged person to respond was Roxanne.

“I called Detective Steve Gallegos within days of the murder,” she wrote. “I provided

important information which to my understanding is not in the case file.”

Those letters provided an impetus for other Albuquerque crime victims to get in touch

with us. One was Nancy Grice, the nurse supervisor who had been on duty on Kait’s

ward the day that she died.

Now it was Nancy’s own daughter who was dead.

“Melanie died in 1995,” Nancy told me. “Her husband, Mark McCracken, a New Mexico

State Police officer, said he found her unconscious on their bed. Instead of calling

for an ambulance, he put her in the back of his car —

ignoring his State Police car with lights, siren and radio, which was also in the

driveway —

drove onto the Indian reservation, and ran the car into a tree. The State Police told

reporters that Melanie died in the car wreck. Mark said she died of leukemia. The

autopsy showed no evidence of either.”

Nancy requested an independent police investigation but was told there was no conflict

of interest.

“No conflict of interest!” she exclaimed, her voice shaking with anger. “Mark’s buddies

were in charge of the investigation! I’ve appealed for help to every agency I can

think of, and everybody’s furious that I won’t let this alone. I even received a call

at work from a homicide detective, threatening to have me arrested for obstructing

justice.”

I hung up the phone and sat staring at my list of homicide survivors. These mothers

had suffered the most excruciating loss any woman could experience and had hung in

there to battle the System in behalf of their dead children. Every one of their names

was engraved on my heart.

Betty’s reading had said that, in a previous life, Michael Bush had been a “Tally

Keeper.”

“It was as if Michael will have been one to come along behind this family of warriors

and take tally. This tally will sometimes have caused him great alarm.”

As I scanned the names on the list of suspicious deaths—

Renee’s son, Peter Klunck

Linda’s son, Nathan Romero

Nancy’s daughter, Melanie McCracken—

I realized with a shudder of horror that now it was I who had become the Tally Keeper.