Operation Mincemeat: How a Dead Man and a Bizarre Plan Fooled the Nazis and Assured an Allied Victory (11 page)

Authors: Ben Macintyre

Tags: #General, #Psychology, #Europe, #History, #Great Britain, #20th Century, #Political Freedom & Security, #Intelligence, #Political Freedom & Security - Intelligence, #Political Science, #Espionage, #Modern, #World War, #1939-1945, #Military, #Italy, #Naval, #World War II, #Secret service, #Sicily (Italy), #Deception, #Military - World War II, #War, #History - Military, #Military - Naval, #Military - 20th century, #World War; 1939-1945, #Deception - Spain - Atlantic Coast - History - 20th century, #Naval History - World War II, #Ewen, #Military - Intelligence, #World War; 1939-1945 - Secret service - Great Britain, #Sicily (Italy) - History; Military - 20th century, #1939-1945 - Secret service - Great Britain, #Atlantic Coast (Spain), #1939-1945 - Spain - Atlantic Coast, #1939-1945 - Campaigns - Italy - Sicily, #Intelligence Operations, #Deception - Great Britain - History - 20th century, #Atlantic Coast (Spain) - History, #Montagu, #Atlantic Coast (Spain) - History; Military - 20th century, #Sicily (Italy) - History, #World War; 1939-1945 - Campaigns - Italy - Sicily, #Operation Mincemeat, #Montagu; Ewen, #World War; 1939-1945 - Spain - Atlantic Coast

Montagu and Cholmondeley were both, in different ways, adapting themselves to the part of Bill Martin. Montagu had forged his signature. Cholmondeley was wearing his clothes. Slowly, the personality of Major Martin was coming into focus, a character that would have to be revealed by whatever was in his wallet, pockets, and briefcase. Martin, it was decided, was the adored son of an upper-middle-class family from Wales. (His Welshness was virtually the only concession to the real identity of the body.) He was a Roman Catholic. Catholic countries were known to be more reluctant to carry out surgical autopsies, and this reluctance would presumably be compounded if the body was thought to be that of a coreligionist. The William Martin they conjured up was clever, even “brilliant,”

21

industrious but forgetful, and inclined to the grand gesture. He liked a good time, enjoyed the theater and dancing, and spent more than he had, relying on his father to bail him out. His mother, Antonia, had died some years earlier. They began to ink in his past. He had been educated, they decided, at public school and university. He was a secret writer of considerable promise, though he had never published anything. After university, he had retired to the country to write, listen to music, and fish. He was something of a loner. With the outbreak of war, he had signed up with the Royal Marines but found himself consigned to an office, which he disliked. “Keen for more active and dangerous

22

work,” he had escaped by switching to the Commandos and had distinguished himself by his aptitude for technical matters, notably the mechanics of landing craft. He had predicted that the Dieppe raid would be a disaster, and he had been right. Martin was, they concluded, “a thoroughly good chap,”

23

romantic and dashing, but also somewhat feckless, unpunctual, and extravagant.

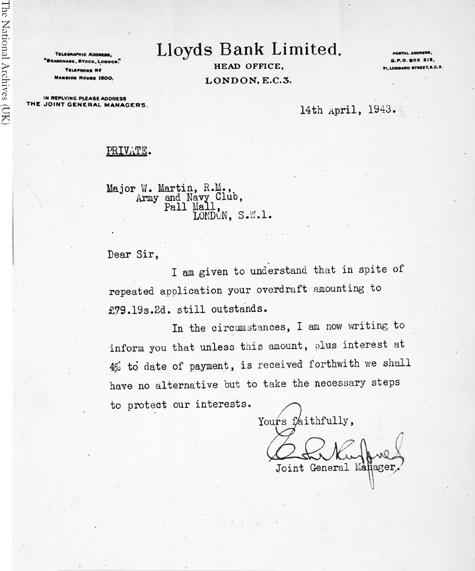

The first witness to Martin’s fictional character was his bank manager. Montagu approached Ernest Whitley Jones, joint general manager of Lloyds Bank, and asked him if he would be prepared to write an angry letter about an overdraft that did not exist, to a client who was also imaginary—a request that is unique in the annals of British banking. Whitley Jones was, perhaps predictably, a cautious man. It was not, he pointed out, normal practice for the general manager of the bank’s head office to perform such a mundane task. But when Montagu explained that he would rather not “bring in” anyone else, the manager relented. Such a letter “could sometimes come from head

24

office,” he said, “especially when the general manager was the personal friend of the father of a young customer whose extravagance needs some check and the father does not want to nag his son.”

14th April, 1943

PRIVATE

Major W. Martin, RM

Army & Navy Club

Pall Mall

London SW1

Dear Sir,

I am given to understand that in spite of repeated application your overdraft amounting to £79.19s.2d still outstands.

In the circumstances, I am now writing to inform you that unless this amount, plus interest at 4% to date of payment, is received forthwith we shall have no alternative but to take the necessary steps to protect our interests.

Yours faithfully,

E. E. Whitley Jones,

Joint General Manager

The dunning letter was addressed to Major Martin at the Army and Naval Club in Pall Mall. This, it was decided, would be Martin’s home when in “town.” Cholmondeley obtained a bill from the club, made out to Major Martin.

Having imagined Martin’s father, Montagu and Cholmondeley now decided this anxious parent deserved a larger part in the unfolding drama. Enter John C. Martin, paterfamilias, “a father of the old school,”

25

in Montagu’s words, who may well have been modeled on his own father: affectionate, but formal and controlling. The letter itself was probably written by Cyril Mills, a colleague in MI5. Mills, the son of the circus impresario Bertram Mills, had taken over the circus business after his father’s death in 1938 and was now one of the key operatives in the Double Cross team. Mills knew how to put on an impressive show. The resulting letter, pompous and pedantic as only an Edwardian father could be, was “a brilliant tour de force.”

26

Tel. No. 98

Black Lion Hotel

Mold

N. Wales

13th April, 1943

My Dear William,

I cannot say that this hotel is any longer as comfortable as I remember it to have been in pre war days. I am, however, staying here as the only alternative to imposing myself once more upon your aunt whose depleted staff & strict regard for fuel economy (which I agree to be necessary in war time) has made the house almost uninhabitable to a guest, at least one of my age. I propose to be in Town for the nights of 20th & 21st of April when no doubt we shall have an opportunity to meet. I enclose the copy of a letter which I have written to Gwatkin of McKenna’s about your affairs. You will see that I have asked him to lunch with me at the Carlton Grill (which I understand still to be open) at a quarter to one on Wednesday the 21st. I should be glad if you would make it possible to join us. We shall not however wait luncheon for you, so I trust that, if you are able to come, you will make a point of being punctual.

Your cousin Priscilla has asked to be remembered to you. She has grown into a sensible girl though I cannot say that her work for the Land Army has done much to improve her looks. In that respect I am afraid that she will take after her father’s side of the family.

Your affectionate

Father

Cholmondeley and Montagu were now enjoying themselves, warming to the task of invention, the depth of detail, the odd plot twists: the exasperated father sorting out his son’s financial affairs, resentful of his sister-in-law’s rule over the family house and of having to stay in a second-class hotel; niece Priscilla, sensible but chunky, with, it was implied, a slight crush on her older cousin Bill; the hints of wartime deprivation and rationing; the artful ink splotch on the first page. Montagu’s acidulous sense of humor ran through every word of the forgeries.

While the larger themes of Martin’s life were being sketched out, Cholmondeley also began to gather the smaller items that a wartime officer might carry in his pockets and wallet, individually unimportant but vital corroborative detail. In modern spy parlance, this is known as “wallet litter,” the little things everyone accumulates that describe who we are and where we have been. Martin’s pocket litter would include a book of stamps, two used; a silver cross on a neck chain and a St. Christopher’s medallion (to emphasize his Catholic piety), a pencil stub, keys; a pack of Player’s Navy Cut cigarettes, the traditional navy smoke; matches; and a used twopenny bus ticket. In his wallet they inserted a pass for Combined Operations Headquarters, which had expired, as further evidence of his lackadaisical attitude to security. The members of Section 17M, all of whom were party to the secret, added their own refinements. There was much discussion over exactly which wartime nightclub Bill might favor. Margery Boxall, Montagu’s secretary, obtained an invitation to the Cabaret Club, a swinging London nightspot, as proof of Martin’s taste for the high life. To this was added a small fragment of a torn letter, written to Bill from an address in Perthshire, relaying some snippet of romantic gossip: “… at the last moment

27

—which was the more to be regretted since he had scarcely ever seen her before. Still, as I told him at the time …” The handwriting is that of John Masterman.

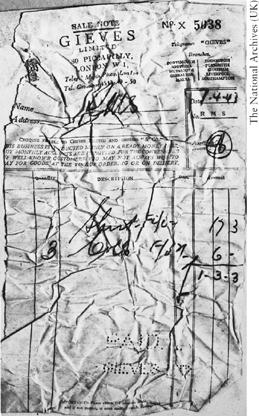

Two identity discs, stamped “M

AJOR

W. M

ARTIN

, R.M., R/C” (Roman Catholic), were attached to the braces that would hold the dead man’s trousers up. A bill for shirts from Gieves, paid in cash, was crumpled up in preparation for stuffing into a pocket. Bill Martin would be carrying cash on his final journey: one five-pound note, three one-pound notes, and some loose change. The banknote numbers were carefully noted. As with all money that might be passed to, or received from, the enemy, the currency was carefully tracked in case it might reappear somewhere significant. If the money disappeared after the body arrived in Spain, it would at least prove that the clothes had been searched.

Nothing was left to chance. Everything the body wore or carried was minutely inspected to ensure that it added to the story, on the assumption that the Germans would make every “effort to find a flaw in

28

Major Martin’s make-up.” And yet something was missing from Martin’s life. It was Joan Saunders who pointed it out: he had no love life. Bill Martin must be made to fall in love. “We decided that a

29

‘marriage would be arranged’ between Bill Martin and some girl just before he was sent abroad,” wrote Montagu. Though he might refer nonchalantly to “some girl,” Montagu already had a girl firmly in mind.

CHAPTER SEVEN

Pam

J

EAN

L

ESLIE WAS JUST EIGHTEEN

in 1941 when she joined the counterintelligence and double-agent section of MI5. Jean was beautiful, in a most English way, with alabaster skin and wavy chestnut hair. She left school at seventeen and was then educated by her upper-class parents in the traditional ladylike skills of typing, secretarial work, and attending debutante parties, but she was far more clever than this might suggest. In fact, she was too clever, from her widowed mother’s point of view. “What on earth are we going to do

1

with Jean?” she worried. A family friend suggested that there might be a suitable job in the War Office. A few weeks later, Jean found herself signing the Official Secrets Act and then plunged into the byzantine business of MI5’s top secret paperwork. Initially, she worked in section B1B, which gathered, filed, and analyzed Ultra decrypts, Abwehr messages, and other intelligence to be used in running the double agents of the Double Cross System. She loved it. The secretarial unit was headed by a sharp-tongued dragon named Hester Leggett, who demanded absolute obedience and perfect efficiency among her “girls.” Jean’s job was to sort through the “yellow perils,” yellow carbon copies of interrogations from Camp 020, the wartime internment center in Richmond, near London, where all enemy spies were grilled. She would read the accounts given by the captured spies and try to spot anything that required the attention of her senior (male) colleagues. It was Jean Leslie who identified the “glaring inconsistencies”

2

in the confession of one Johannes de Graaf, a Belgian agent. De Graaf was subsequently found to be playing a triple game. Jean was delighted with herself, and then distraught, when it appeared that de Graaf would face execution.

The all-female secretarial team was known as “the Beavers,” and the most eager beaver of all was young Jean Leslie. “I was frightfully willing

3

to help, always. I ran everywhere. I was so keen to please.” Hester Leggett, rather cruelly nicknamed “The Spin,” for “spinster,” repeatedly reprimanded her for sprinting through the hushed offices in St. James’s Street: “Don’t run, Miss Leslie!”

4