Operation Mincemeat: How a Dead Man and a Bizarre Plan Fooled the Nazis and Assured an Allied Victory (12 page)

Authors: Ben Macintyre

Tags: #General, #Psychology, #Europe, #History, #Great Britain, #20th Century, #Political Freedom & Security, #Intelligence, #Political Freedom & Security - Intelligence, #Political Science, #Espionage, #Modern, #World War, #1939-1945, #Military, #Italy, #Naval, #World War II, #Secret service, #Sicily (Italy), #Deception, #Military - World War II, #War, #History - Military, #Military - Naval, #Military - 20th century, #World War; 1939-1945, #Deception - Spain - Atlantic Coast - History - 20th century, #Naval History - World War II, #Ewen, #Military - Intelligence, #World War; 1939-1945 - Secret service - Great Britain, #Sicily (Italy) - History; Military - 20th century, #1939-1945 - Secret service - Great Britain, #Atlantic Coast (Spain), #1939-1945 - Spain - Atlantic Coast, #1939-1945 - Campaigns - Italy - Sicily, #Intelligence Operations, #Deception - Great Britain - History - 20th century, #Atlantic Coast (Spain) - History, #Montagu, #Atlantic Coast (Spain) - History; Military - 20th century, #Sicily (Italy) - History, #World War; 1939-1945 - Campaigns - Italy - Sicily, #Operation Mincemeat, #Montagu; Ewen, #World War; 1939-1945 - Spain - Atlantic Coast

This beautiful young woman who ran everywhere had caught the eye of Ewen Montagu. Jean could not fail to notice how the friendly and undoubtedly handsome older officer seemed to pay her special attention. “In fact, he was trailing me

5

a bit. He was rather smitten.” Indeed he was: Montagu’s writings, official and unofficial, describe her variously as “charming,”

6

“very attractive,”

7

and other admiring adjectives.

In mid-February, the hunt began for a suitable mate for Major Martin. “The more attractive girls in

8

our various offices” were asked to supply photographs for use in an identity parade. Montagu made a point of asking Miss Leslie if she would oblige. “I think he had every intention

9

of getting one off me somehow,” she said later. That evening, Jean, now twenty, keen as ever and rather flattered by the attention, ransacked her dressing-room drawer for a recent photograph. With the bombing of London, Mrs. Leslie had moved out of London, to a borrowed house on the Thames near Dorchester in Oxfordshire, where her daughter spent weekends. A few weeks earlier, Jean had gone swimming in the river at Wittenham Clumps with Tony, a grenadier guard on leave who, like Montagu, was smitten, and was about to return to the war. “The swimming there was horrible,”

10

she recalled, but the occasion had been a happy one. Tony had taken a photograph, which he sent to her afterward. In it, Jean has just emerged from the water in a patterned one-piece swimsuit, with towel held demurely, hair windswept, and a sweet grin on her face. In 1940s England, the image was not just attractive but very nearly saucy, and both Jean Leslie and Ewen Montagu knew it.

The request for photographs had garnered “quite a collection.”

11

It was no accident that the Naval Intelligence Department contained a high ratio of particularly attractive women. “Uncle John gave specific orders

12

that only the prettiest girls should be employed, on the theory that then they would be less likely to boast to their boyfriends about the secret work they were doing.” Some of Montagu’s female colleagues in Room 13 were distinctly put out when he selected a photograph of a woman from another department: “We were all rather jealous,”

13

recalled Patricia Trehearne, one of his assistants. But there was never any doubt who would win this particular beauty contest. Jean’s photograph was added to the growing pile of Martin’s possessions, and a new and central character was worked into the unfolding plot: this was “Pam,” his new fiancée, a vivacious young woman working in a government office, who was excitable, pretty, gentle, and really quite dim. It was decided that Bill had met Pam just five weeks earlier and had proposed to her after a whirlwind romance, buying a large and expensive diamond ring for the purpose. John Martin, his father, did not approve, suspecting Pam might be something of a gold digger. No date for the wedding had been set. Here was a typical wartime romance: sudden, thrilling, and, as matters would shortly turn out, doomed.

Jean Leslie had sufficient security clearance to be partially inducted into the secret. Montagu told her that the photograph depicted a fictitious fiancée, as part of a deception plan. “I knew it was going to be planted

14

on a body, but I didn’t know where.” Charles Cholmondeley later took Jean aside and asked her in serious tones: “Has anybody else got that

15

photograph? If so, you should ask for it back. If you gave it to someone and they were going out on the second front and were captured and this photograph was discovered in his possession, the consequences could be very serious.” Jean contacted Tony, the grenadier guard, and told him to destroy any other copies of the photograph. Hurt, Tony complied. Montagu also took Jean aside and impressed upon her the need for absolute secrecy. Then he asked her out to dinner. She accepted.

Montagu adored his wife, Iris. “I never realised how lonely

16

and really empty life could be just because you weren’t there,” he wrote. His wartime letters are passionate, peppered with rude jokes, poems, and stories and haunted by the fear that they might be parted forever: “How ultra-happy our life was

17

before this bloody business started. … Bugger Hitler.” Whenever Iris’s letters were delayed from New York, he would half joke: “You must have gone off

18

with an American.” But he longed for female company. “I am always the gooseberry,”

19

he complained. He declined an invitation to a dance, although he longed to go: “It was a question of whether

20

there was a girl I could take, I literally couldn’t think of anyone, not even anyone to try.” Jean Leslie was single, extremely pretty, and good company. Ewen did not try to conceal his first date with Jean from his wife, but he did not dwell on it, either. “I took a girl from the office

21

to Hungaria [a restaurant] and had dinner and danced. She is an attractive child.”

Bill would need love letters to go with his photograph of Pam. The job of drafting these fell to Hester Leggett, “The Spin,” the most senior woman in the department. Jean remembered her as “skinny and embittered.”

22

Hester Leggett was certainly fierce and demanding. She never married, and she devoted herself utterly to the job of marshaling a huge quantity of secret paperwork. But into Pam’s love letters she poured every ounce of pathos and emotion she could muster. These letters may have been the closest Hester Leggett ever came to romance: chattering pastiches of a young woman madly in love, and with little time for grammar.

The Manor House

Ogbourne St George

Marlborough, Wiltshire

Telephone Ogbourne St. George 242

Sunday 18th

I do think dearest that seeing people like you off at railway stations is one of the poorer forms of sport. A train going out can leave a howling great gap in ones life & one had to try madly—& quite in vain—to fill it with all the things one used to enjoy a short five weeks ago. That lovely golden day we spent together oh! I know it has been said before, but if only time could stand still for just a minute—But that line of thought is too pointless. Pull your socks up Pam & don’t be a silly little fool.

Your letter made me feel slightly better—but I shall get horribly conceited if you go on saying things like that about me—they’re utterly unlike ME, as I’m afraid you’ll soon find out. Here I am for the weekend in this divine place with Mummy & Jane being too sweet and understanding the whole time, bored beyond words & panting for Monday so that I can get back to the old grindstone again. What an idiotic waste!

Bill darling, do let me know as soon as you get fixed & can make some more plans, & don’t please let them send you off into the blue the horrible way they do nowadays—now that we’ve found each other out of the whole world, I don’t think I could bear it.

All my love, Pam

The personalized notepaper (obtained from Montagu’s brother-in-law) was used on the basis that “no German could resist the ‘Englishness’”

23

of such an address. The next letter, dated three days later, was on plain paper, written by Pam in a frantic rush as her boss, “The Bloodhound,” threatened to return from lunch at any moment. As the official report on Operation Mincemeat acknowledged, Hester Leggett’s effort “achieved the thrill and pathos

24

of a war engagement with great success.”

Office

Wednesday 21st

The Bloodhound has left his kennel for half an hour so here I am scribbling nonsense to you again. Your letter came this morning just as I was dashing out—madly late as usual! You do write such heavenly ones. But what are these horrible dark hints you’re throwing out about being sent off somewhere—of course I won’t say a word to anyone—I never do when you tell me things, but it’s not abroad is it? Because I won’t have it, I WON’T, tell them so from me. Darling, why did we go and meet in the middle of a war, such a silly thing for anybody to do—if it weren’t for the war we might have been nearly married by now, going round together choosing curtains etc. And I wouldn’t be sitting in a dreary Government office typing idiotic minutes all day long—I know the futile work I do doesn’t make the war one minute shorter—Dearest Bill, I’m so thrilled with my ring—scandalously extravagant—you know how I adore diamonds—I simply can’t stop looking at it.

I’m going to a rather dreary dance tonight with Jock & Hazel, I think they’ve got some other man coming. You know what their friends always turn out to be like, he’ll have the sweetest little Adam’s apple & the shiniest bald head! How beastly and ungrateful of me, but it isn’t really that—you know—don’t you?

Look darling, I’ve got next Sunday & Monday off for Easter. I shall go home for it, of course, do come too if you possibly can, or even if you can’t get away from London I’ll dash up and we’ll have an evening of gaiety—(by the way Aunt Marian said to bring you to dinner next time I was up, but I think that might wait?)

Here comes the Bloodhound, masses of love & a kiss from

Pam

Hester Leggett ended the second letter with a flourish, as Pam’s looping, girlish handwriting collapses into a hasty scrawl.

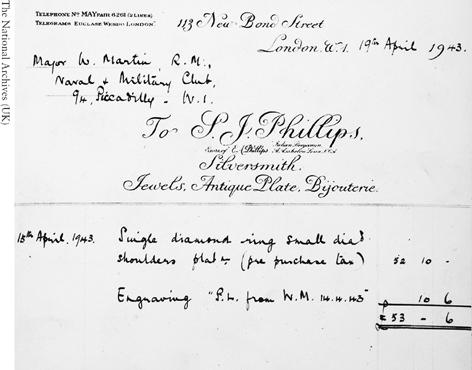

For good measure, Montagu and Cholmondeley added to Martin’s wallet a bill for an engagement ring from S.J. Phillips of New Bond Street, for a whopping £53.0s.6d. The ring was engraved “P.L. from W.M. 14.4.43.”

25

Two more letters rounded off Martin’s personal cache. The first was from his solicitor, F. A. S. Gwatkin, of McKenna & Co., referring to his will and tax affairs: “We will insert the legacy of £50

26

to your batman,” wrote Mr. Gwatkin, who regretted that he could not yet complete Martin’s tax return for 1941–1942: “We cannot find that we have ever had these particulars and shall, therefore, be grateful if you will let us have them.” On top of everything else, Major Martin’s tax return was overdue. Finally, there was another letter from John Martin, this time a copy of a letter to the family solicitor, discussing the terms of his son’s marriage settlement and insisting that “since the wife’s family will not

27

be contributing to the settlement I do not think it proper that they should preserve, after William’s death, a life interest in the funds which I am providing. I should agree to this course only were there children of the marriage.”

Montagu and Cholmondeley were delighted with the plot they had created, with its looming premonition of disaster, a dashing but flawed hero, a sexy, faintly dippy heroine, and a rich cast of comic supporting characters: The Bloodhound, Father, Fat Priscilla, and Whitley Jones the Bank Manager. But from a distance of nearly seventy years, the plot seems almost hackneyed. The sense of impending doom and Pam’s “foreboding” are thumpingly melodramatic: “Bill darling, don’t please let them send you off into the blue the horrible way they do. …”