Operation Mincemeat: How a Dead Man and a Bizarre Plan Fooled the Nazis and Assured an Allied Victory (23 page)

Authors: Ben Macintyre

Tags: #General, #Psychology, #Europe, #History, #Great Britain, #20th Century, #Political Freedom & Security, #Intelligence, #Political Freedom & Security - Intelligence, #Political Science, #Espionage, #Modern, #World War, #1939-1945, #Military, #Italy, #Naval, #World War II, #Secret service, #Sicily (Italy), #Deception, #Military - World War II, #War, #History - Military, #Military - Naval, #Military - 20th century, #World War; 1939-1945, #Deception - Spain - Atlantic Coast - History - 20th century, #Naval History - World War II, #Ewen, #Military - Intelligence, #World War; 1939-1945 - Secret service - Great Britain, #Sicily (Italy) - History; Military - 20th century, #1939-1945 - Secret service - Great Britain, #Atlantic Coast (Spain), #1939-1945 - Spain - Atlantic Coast, #1939-1945 - Campaigns - Italy - Sicily, #Intelligence Operations, #Deception - Great Britain - History - 20th century, #Atlantic Coast (Spain) - History, #Montagu, #Atlantic Coast (Spain) - History; Military - 20th century, #Sicily (Italy) - History, #World War; 1939-1945 - Campaigns - Italy - Sicily, #Operation Mincemeat, #Montagu; Ewen, #World War; 1939-1945 - Spain - Atlantic Coast

The later date would also “enable the operation to be carried

46

out with a waning moon in a reasonably dark period (approximately 28th–29th April).” Jewell arrived at Submarine Headquarters, a block of flats requisitioned in Swiss Cottage, north London, where Rear Admiral Barry told him to go to an address in St. James. There he was greeted by Montagu, Cholmondeley, Captain Raw, chief staff officer to Admiral Submarines, and a set of operational orders laying out his mission.

Ronnie Reed, the MI5 case officer who “might have been the twin brother” of Glyndwr Michael.

Lieutenant Norman Limbury Auchinleck Jewell was thirty years old, with a cheerful grin and bright blue eyes. Understated and charming, Bill Jewell, as he was known, was also tough as teak, ruthless, occasionally reckless, and entirely fearless. He had seen fierce action in the Mediterranean and the Atlantic. His submarine had been depth charged, torpedoed, machine-gunned, and mistakenly shot at by the RAF; he had spent seventy-eight hours slowly suffocating with his crew in a half-crippled submarine at the bottom of the sea; he had taken part in several clandestine operations that, had they been intercepted, might have led to espionage charges and a German firing squad. In four years of watery war, Jewell had seen so much secrecy, strangeness, and violence that the request to deposit a dead body in the sea off Spain did not remotely faze him. “In wartime, any plan that saved

47

lives was worth trying,” he reflected.

Jewell was never informed of the identity of the body or the exact nature of the papers it was carrying, and he hardly needed to be told of “the vital need for secrecy.”

48

The tall man with the extravagant mustache was introduced as “a squadron leader for RAF intelligence.” The body, Cholmondeley explained, would be brought to him in Scotland, “packed, fully clothed and ready,”

49

inside a large steel tube. This canister could be lifted by two men but should on no account be dragged by a single handle, “as the steel is made of light gauge

50

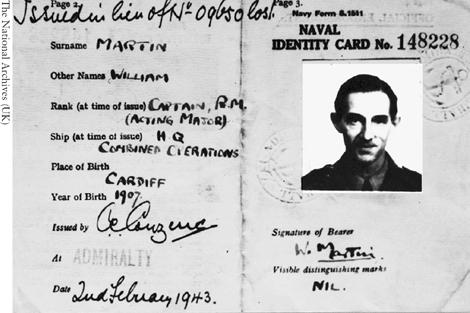

to keep the weight as low as possible,” and it might give way if roughly handled. The possibility of the container breaking and the body falling out was too awful to contemplate. The canister would fit down the torpedo hatch and could then be hidden belowdecks. Jewell would also receive a rubber dinghy in a separate package, a locked briefcase with chain attached, and three separate identity cards for William Martin, with three different photographs. In idle moments, Montagu had taken to rubbing Martin’s fake identity cards on his trouser leg to give them the patina of use.

What, Jewell asked, should he tell the men under his command about this large object on his small ship? Montagu explained that the lieutenant could take his officers into his confidence once under way, but that the rest of the crew should be told only that the container “held a super-secret automatic

51

meteorological reporting apparatus, and that it was essential that its existence and position should not be given away or it would be removed by the Spaniards and the Germans would learn of its construction.”

Jewell pointed out that if the weather was rough, the officers might need the help of the crew to get the canister up on deck. If a member of the crew spotted the body, he was instructed, he should be told that “we suspected the Germans

52

of getting at papers on bodies washed ashore and therefore this body was going to be watched: if our suspicions were right the Spaniards would be asked to remove the Germans concerned.” This cover story could also be told to the officers, but “Lt Jewell was to impress

53

on [them] that they would never hear the result and that if anything leaked out about this operation not only would the dangerous German agents not be removed, but the lives of those watching what occurred would be endangered.”

Upon reaching a position “between Portil Pillar and Punta Umbria

54

just west of the mouth of the Rio Tinto River,” Jewell should assess the weather conditions. “Every effort should be made

55

to choose a period with an onshore wind.” Jewell studied the charts and estimated “the submarine could probably

56

bring the body close enough inshore to obviate the need to use a rubber dinghy.” Cholmondeley had originally envisaged setting off an explosion out at sea to simulate an air crash, but after some discussion “the proposed use of a flare was dropped.”

57

There was no point in attracting any unnecessary attention.

Under cover of darkness, the canister should be brought up through the torpedo hatch “on specially prepared slides

58

and lashed to the rail of the gun platform.” Any crew members should then be sent below, leaving only the officers on deck. “The container should then be opened

59

on deck as the ‘dry-ice’ will give off carbon dioxide.” It would also smell terrible.

Montagu and Cholmondeley had given a great deal of thought to exactly how the briefcase should be attached to Major Martin. No one, even the most assiduous officer, would sit on a long flight with an uncomfortable chain running down his arm. “When the body is removed

60

from the container,” they told Jewell, “all that will be necessary will be to fasten the chain attached to the briefcase through the belt of the trench coat which will be the outer garment of the body … as if the officer has slipped the chain off for comfort in the aircraft, but has nevertheless kept it attached to him so that the bag should not either be forgotten or slide away from him in the aircraft.” Jewell should decide which of the three identity cards most closely resembled the dead man in his current state, and put this in his pocket. The body, with life jacket fully inflated, should then be slipped over the side. The inflated dinghy should also be dropped, and perhaps an oar, “near the body but not too near

61

if that is possible.” Jewell’s final task would be to reseal the canister, sail into deep water, and then sink it.

If, for any reason, the operation had to be abandoned, then “the body and container

62

should be sunk in deep water,” and if it was necessary to open the canister to let water in, “care must be taken that

63

the body does not escape.” A signal should be sent with the words: “Cancel Mincemeat.”

64

If the drop was successful, then another message should be sent: “Mincemeat completed.”

65

Jewell noted that the two intelligence officers seemed utterly absorbed by the project and had obviously had “a pleasant time building up

66

a character.” Before the meeting broke up, Montagu asked the young submariner if he would like to contribute, in a small way, to “making a life for the Major of Marines.”

67

A nightclub ticket was needed for the dead man’s wallet. Would Lieutenant Jewell care to spend a night on the town, and then send over the documentary evidence? “I had the enjoyment

68

of going around London nightclubs on his ticket,” said Jewell. “It was an enjoyable period.”

While Jewell returned north with his new operational orders and a slight hangover, another telegram was dispatched to General Eisenhower in Algiers. “Mincemeat sails

69

19th April and operation probably takes place 28th April but could if necessary be cancelled on any day up to and including 26th April.”

If all went according to plan, Major Martin would wash up in Spain on or soon after April 28, where an extraordinary reception was being prepared for him by Captain Alan Hillgarth, naval attaché in Madrid, spy, former gold prospector, and, perhaps inevitably, successful novelist.

CHAPTER ELEVEN

Gold Prospector

I

N HIS SIX NOVELS

, Alan Hillgarth hankered for a lost age of personal valor, chivalry, and self-reliance. “Adventure was once a noble

1

appellation borne proudly by men such as Raleigh and Drake,” he wrote in

The War Maker

, but it is now “reserved for the better-dressed members of the criminal classes.” Hillgarth’s own life read like something out of the

Boy’s Own Paper

or the pages of Rider Haggard.

The son of a Harley Street ear, nose, and throat surgeon, Hillgarth had entered the Royal Naval College at the age of thirteen, fought in the First World War as a fourteen-year-old midshipman (his first task was to assist the ship’s doctor during the Battle of Heligoland Bight by throwing amputated limbs overboard), and skewered his first Turk, with a bayonet, before his sixteenth birthday. At Gallipoli he found himself in charge of landing craft, as all the other officers had been killed. He was shot in the head and leg and spent the recovery time learning languages and cultivating a passion for literature. Hillgarth was small and fiery, with dense, bushy eyebrows and an inexhaustible supply of energy. He was also an arborphile: he loved trees and was never happier than in forest or jungle.

In 1927, Evelyn Waugh recalled his first meeting with “a young man called Alan Hillgarth,

2

very sure of himself, writes shockers, ex-sailor.” By this time, Hillgarth had embarked on a second career as a novelist, a third as adviser to the Spanish Foreign Legion during the uprising of the Rif tribes in Morocco, and a fourth as a “King’s Messenger” carrying confidential messages on behalf of the government. But it was Hillgarth’s fifth career, as a treasure hunter, that defined the rest of his life—and the next stage of Operation Mincemeat.

In 1928, Hillgarth met Dr. Edgar Sanders, a Swiss adventurer born in Russia and living in London, who told him a most intriguing story. Sanders had traveled to the interior of Bolivia in 1924, lured by legends of a vast hoard of gold, the treasure of Sacambaya, mined by the Jesuits and hidden before they were expelled from South America in the eighteenth century. Sanders showed Hillgarth a document, given to him by one Cecil Prodgers, a Boer War veteran and rubber tapper, who claimed to have obtained it from the family of an elderly Jesuit priest. The document identified the hiding place of the gold as a “steep hill all covered

3

with dense forest … from where you can see the River Sacambaya on three sides,” topped by “a large stone shaped like an egg.”

4

Beneath the stone, according to the account, lay a network of underground caverns “that took five hundred men

5

two-and-one-half years to hollow out.” The gold inside was protected by “enough strong poison to kill

6

a regiment.”

Sanders claimed to have found the site amid the ruins of a once-great Jesuit colony at a place called Inquisivi, deep in the remote Quimsa Cruz range of the eastern Andes. Nearby, Sanders claimed to have found hundreds of skulls, “reputed by the local Indians

7

to be those of the slaves who were engaged in burying the treasure and then massacred by the Jesuits to prevent them divulging the secret.”