Operation Mincemeat: How a Dead Man and a Bizarre Plan Fooled the Nazis and Assured an Allied Victory (18 page)

Authors: Ben Macintyre

Tags: #General, #Psychology, #Europe, #History, #Great Britain, #20th Century, #Political Freedom & Security, #Intelligence, #Political Freedom & Security - Intelligence, #Political Science, #Espionage, #Modern, #World War, #1939-1945, #Military, #Italy, #Naval, #World War II, #Secret service, #Sicily (Italy), #Deception, #Military - World War II, #War, #History - Military, #Military - Naval, #Military - 20th century, #World War; 1939-1945, #Deception - Spain - Atlantic Coast - History - 20th century, #Naval History - World War II, #Ewen, #Military - Intelligence, #World War; 1939-1945 - Secret service - Great Britain, #Sicily (Italy) - History; Military - 20th century, #1939-1945 - Secret service - Great Britain, #Atlantic Coast (Spain), #1939-1945 - Spain - Atlantic Coast, #1939-1945 - Campaigns - Italy - Sicily, #Intelligence Operations, #Deception - Great Britain - History - 20th century, #Atlantic Coast (Spain) - History, #Montagu, #Atlantic Coast (Spain) - History; Military - 20th century, #Sicily (Italy) - History, #World War; 1939-1945 - Campaigns - Italy - Sicily, #Operation Mincemeat, #Montagu; Ewen, #World War; 1939-1945 - Spain - Atlantic Coast

Montagu, meanwhile, contacted Admiral Sir Claude Barry, the flag officer in command of submarines (FOS) to find out which submarine might best be used for the mission. Barry replied that British submarines passed Huelva frequently en route to Malta; indeed, HMS

Seraph

was currently in Scotland, docked at Holy Loch on the Clyde and preparing to return to the Mediterranean in April. The

Seraph

was commanded by Lieutenant Bill Jewell, a young captain who had already carried out several secret assignments and who could be relied on for complete discretion. Montagu drew up some draft operational orders for Jewell and arranged to meet the submarine officer in London and give him a full briefing on his new mission.

The hydrographer at the Admiralty submitted his report on the winds and tides off the coast at Huelva. As befits a man immersed in the vagaries of marine conditions, he was distinctly noncommittal, pointing out that “the Spaniards and Portuguese

12

publish practically nothing about tides, tidal streams and currents off their coasts.” Moreover, “the tides in that area

13

run mainly up and down the coast.” If the object was dropped in the right place, in the right conditions, “wind between S[outh] and W[est]

14

might set it towards the head of the bight near P. Huelva.” However, if the body did wash up on the shore, there was no guarantee it would stay there because “if it did not strand,

15

it would be carried out again on the ebb.” This was less than perfect, but not discouraging enough to call off the operation. In any case, Montagu reflected, the “object” in question was a man in a life jacket, rather larger than the object the hydrographer had been asked to speculate about, and might be expected to catch an onshore wind and drift landward. He concluded: “The currents on the coast

16

are unhelpful at any point but the prevailing south west wind will bring the body ashore if Jewell can ditch it near enough to the coast.”

In the last week of March, Montagu drew up a seven-point progress report for Johnnie Bevan, who had just returned from North Africa, where he had coordinated plans for Operation Barclay with Lieutenant Colonel Dudley Clarke. Relations between Montagu and Bevan remained tense. “I am not quite clear as to who

17

is in sole charge of administrative arrangements in connection with this operation,” Bevan wrote to Montagu, in a note calculated to rile him. “I think we all agree that there are quite a number of things that might go wrong.” Montagu was fully aware of the dangers and in no doubt whatsoever that he was in sole charge of the operation, even if Bevan did not see it that way. Privately, Montagu accused Bevan of “thinking it couldn’t come off

18

and disclaiming all responsibility.”

Montagu’s report laid out the state of play: the body was almost ready, with Major Martin’s uniform and accoutrements selected; the canister was under construction; Gómez-Beare and Hillgarth were standing by in Spain. And there was now a deadline: “Mincemeat will be taken out

19

as an inside passenger in HMS Seraph leaving the northwest coast of this country probably on the 10th April.” That left just two weeks to complete preparations. Montagu and Cholmondeley had deliberately sought to arrange everything before obtaining final approval for the operation, on the assumption that senior officers were far less likely to meddle when presented with a fait very nearly accompli. But there was now little time to finalize the last, and by far the most important, piece of the puzzle. Montagu’s letter to Bevan ended on a note of exasperation: “All the details are now

20

‘buttoned up,’” he wrote. “All that is required are the official documents.”

The debate about what should, or should not, be contained in Major Martin’s official letters had already taken up more than a month. It is doubtful whether any documents in the war were subjected to closer scrutiny or more revisions. Draft after draft was proposed by Montagu and Cholmondeley, revised by more senior officers and committees, scrawled over, retyped, sent off for approval, and then modified, amended, rejected, and rewritten all over again. There was general agreement that, as Montagu had originally envisaged, the keystone of the deception should be a personal letter from General Nye to General Alexander. It was also agreed that the letter should identify Greece as the target of the next Allied assault and Sicily as the cover target. Beyond this, there was very little agreement about anything at all.

Almost everyone who read the letter thought it could do with “alteration and improvement.”

21

Everyone, and every official body concerned, from the Twenty Committee to the Chiefs of Staff, had a different idea about how this should be achieved. The Admiralty thought it needed to be “more personal.”

22

The Air Ministry insisted the letter should clearly indicate that the bombing of Sicilian airfields was in preparation for invading Greece, and not a prelude to an attack on Sicily itself. The chief of the Imperial General Staff and chairman of the Chiefs of Staff, General Sir Alan Brooke, wanted “a letter in answer to one from

23

General Alexander.” The director of plans thought the operation was premature and “should not be undertaken

24

earlier than two months before the real operation,” in case the real plans changed. Bevan wondered whether the draft letter sounded “rather too official”

25

and insisted, “we must get Dudley Clarke’s

26

approval as it’s his theatre.” Clarke himself, in a flurry of cables from Algiers, warned of the “danger of overloading

27

this communication” and stuck to the view that it was “a mistake to play for high

28

deception stakes.” Bevan remained anxious: “If anything miscarries

29

and the Germans appreciate that the letter is a plant they would no doubt realise that we intend to attack Sicily.” Clarke framed his own draft, further enraging Montagu, who regarded this effort as “merely a lowish grade innuendo

30

at the target of the type that has often been, and could always be, put over by a double agent.” The director of plans agreed that “Mincemeat should be capable

31

of much greater things.” Bevan then also tried his hand at a letter, which again Montagu dismissed as “of a type which could have

32

been sent by signal and would not have appeared genuine to the Germans if carried in the way this document would be.” There was even a brief but fierce debate over how to spell the name of the Greek city Kalamata. The operation seemed to be running into a swamp of detail.

Typically, Montagu tried to insert some tongue-in-cheek jokes into the letter. He wanted Nye to write: “If it isn’t too much trouble,

33

I wonder whether you could ask one of your ADCs to send me a case of oranges or lemons. One misses fresh fruit terribly, especially this time of year when there is really nothing to buy.” The Chiefs of Staff excised this: General Nye could not be made to look like a scrounger. Even to the Germans. Especially to the Germans. So Montagu tried another line: “How are you getting on

34

with Eisenhower? I gather he is not bad to work with. …” That was also removed: too flippant for a general. Next Montagu attempted a quip at the expense of the notoriously bigheaded General Montgomery: “Do you still take the same size

35

in hats, or do you need a couple of sizes larger like Monty?” That, too, was censored. Finally, Montagu managed to squeeze a tiny half joke in at the end, relating to Montgomery’s much-mocked habit of issuing orders every day. “What is wrong with Monty?

36

He hasn’t issued an order of the day for at least 48 hours.” That stayed in, for now.

Montagu’s temper, never slow to ignite, began smoldering dangerously as the deadline neared and the key letter was tweaked, poked, and polished. And then scrapped and restarted. Page after page of drafts went into the files, covered with Montagu’s increasingly enraged squiggles and remarks.

Finally, the Chiefs of Staff came up with a good suggestion: why not have General Nye draft the letter himself, since this would be “the best way of giving it

37

an authentic touch”? Archie Nye was no wordsmith, but he knew General Alexander fairly well, and he knew the sound of his own voice. Nye read all the earlier drafts and then put the letter into his own words. The key passage referred to General Sir Henry “Jumbo” Wilson, then commander-in-chief of the Middle East, making it appear that he would be spearheading an attack on Greece; it indicated, falsely, that Sicily was being set up as a cover target for a simultaneous assault in another part of the Mediterranean; it referred to some run-of-the-mill army matters, which also happened to be authentic, such as the appointment of a new commander of the Guards Brigade and an offer from the Americans to award Purple Hearts to British soldiers serving alongside American troops. Above all, it sounded right. Montagu, after so many weeks spent trying to pull off the forgery himself, admitted that Nye’s letter was “ideally suited to the purpose.”

38

The false targets were “not blatantly mentioned

39

although very clearly indicated,” allowing the enemy to put two and two together, making at least six.

Bevan wrote to Nye, asking him to have the letter typed up and then to sign it in nonwaterproof ink, since a waterproof signature might raise suspicions. “Your signature in ink might

40

become illegible owing to contact with sea water and consequently it would be advisable to type your full title and name underneath the actual signature.”

Bevan had one final tweak. “General Wilson is referred to

41

three times as ‘Jumbo,’ ‘Jumbo Wilson’ and ‘Wilson.’ I wonder whether it would not be more plausible to refer to him on the first occasion as ‘Jumbo Wilson’ and ‘Jumbo’ thereafter.”

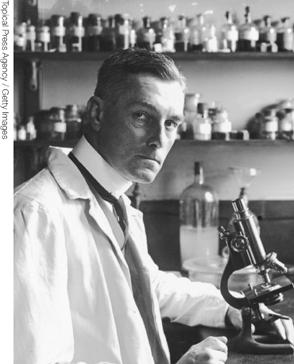

Ewen Montagu, naval intelligence officer, lawyer, angler, and the principal organizer of Operation Mincemeat.

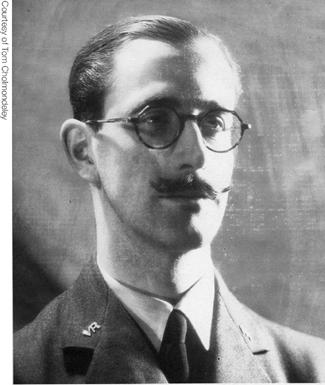

Charles Cholmondeley, the RAF officer seconded to MI5 whose “corkscrew mind” first alighted on the idea of using a dead body to deceive the Germans.