Operation Mincemeat: How a Dead Man and a Bizarre Plan Fooled the Nazis and Assured an Allied Victory (17 page)

Authors: Ben Macintyre

Tags: #General, #Psychology, #Europe, #History, #Great Britain, #20th Century, #Political Freedom & Security, #Intelligence, #Political Freedom & Security - Intelligence, #Political Science, #Espionage, #Modern, #World War, #1939-1945, #Military, #Italy, #Naval, #World War II, #Secret service, #Sicily (Italy), #Deception, #Military - World War II, #War, #History - Military, #Military - Naval, #Military - 20th century, #World War; 1939-1945, #Deception - Spain - Atlantic Coast - History - 20th century, #Naval History - World War II, #Ewen, #Military - Intelligence, #World War; 1939-1945 - Secret service - Great Britain, #Sicily (Italy) - History; Military - 20th century, #1939-1945 - Secret service - Great Britain, #Atlantic Coast (Spain), #1939-1945 - Spain - Atlantic Coast, #1939-1945 - Campaigns - Italy - Sicily, #Intelligence Operations, #Deception - Great Britain - History - 20th century, #Atlantic Coast (Spain) - History, #Montagu, #Atlantic Coast (Spain) - History; Military - 20th century, #Sicily (Italy) - History, #World War; 1939-1945 - Campaigns - Italy - Sicily, #Operation Mincemeat, #Montagu; Ewen, #World War; 1939-1945 - Spain - Atlantic Coast

Gaunt, introverted, and unsociable, Adolf Clauss nonetheless possessed the spy’s essential talent for listening. “He didn’t dispute;

55

if you thought you had the right argument, he always let you have the last word.” But even his family found him “cold, distant and silent.”

56

He started work at six in the morning and never took a siesta. He seldom drank alcohol. He almost never smiled. His was the mind of the collector, the perfectionist. He liked to collate the different sorts of information from his intelligence network and then to pin them down, in different compartments, like butterflies.

The British authorities in Huelva knew what the odd-looking German lepidopterist was up to, for the British had their own spies and informers. In Huelva’s peaceful, orange tree–lined streets, another spy contest was under way, a smaller but no less intense echo of the espionage battle taking place in Madrid. The Clauss spy network was a menace to British shipping. Countless lives had already been forfeited on account of his activities, yet Clauss was an elusive adversary. As one British intelligence officer put it: “He was an active and intelligent

57

person. It was impossible for any of our agents to watch him and keep tabs on him. He was sharper and gave the slip to anyone who followed him.”

Don Gómez-Beare described the Clauss network to Montagu and Cholmondeley. Some of what he said was familiar. The decoding of Abwehr messages had revealed, early in the war, the existence in Huelva of this “very efficient German agent

58

who had the majority of Spanish officials there working for him, either for pay or for fascist ideology.” For more than three years, Montagu had monitored the steady buildup of German espionage activity in southern Spain, the use of Spanish territorial waters by German U-boats, and the activities of what he called this “super-super efficient agent”

59

in Huelva with “first rate”

60

sources, who seemed to own the town: “No ship can move without being

61

seen, named and reported by W/T [wireless telegraphy]. The Germans get reports from lighthouse keepers, fishing boats, pilots and navy vessels, and agents in neutral fishing boats.” When the Germans began building an infrared spotting system to track ships passing through the Strait of Gibraltar at night, Churchill briefly considered launching a commando raid against the installation. Only the most vigorous diplomatic objections from the British government persuaded the Spanish to intervene and have it removed. For the most part, the Spanish government quietly tolerated, or actively condoned, the German espionage and sabotage of British and Allied ships.

Gibraltar, just fifty miles south of Huelva, was Britain’s key to the Mediterranean, “one of the most difficult

62

and complicated places on the map,” in John Masterman’s words. The Rock guarded the gateway to the sea, a pivotal British outpost on the Spanish coast and a magnet for spies. As MI5’s senior officer on the island wrote, in a burst of lyricism: Gibraltar was “the tiniest jewel in the imperial

63

crown … this strategic dot on the world’s map is not only a colony: it is also a garrison town, a naval base, a commercial port, a civil and military aerodrome, and a shop-window for Britain in Europe.” The Abwehr funneled money to willing Spanish saboteurs in Gibraltar and the surrounding region through one Colonel Rubio Sánchez, code-named “Burma,” the chief of military intelligence in the Algeciras region. Sánchez was distributing five thousand pesetas a month to saboteurs in and around Gibraltar. So far, the damage was limited since, as the MI5 chief in Gibraltar pointed out, the saboteurs’ “mercenary instincts were

64

more outstanding than either their efficiency or their enthusiasm.” Montagu believed that special intelligence had successfully foiled several sabotage attempts, but the threat from German espionage in southern Spain was growing. In the month that Operation Mincemeat was born, Montagu warned that German sabotage had “increased and spread”

65

and was now being actively pursued by the Nazis and their collaborators “in all Spanish and Spanish owned ports.”

66

Adolf Clauss had, so far, enjoyed a most pleasant and productive war. In Madrid and Berlin he was held in high esteem as “one of the most important,

67

active and intelligent German agents in the South of Europe.” Even NID and MI6 had a healthy respect for his manipulative skills. His network of spies and informers extended from Valencia to Seville. If anything of importance or interest washed up within fifty miles of the Café de la Palma, let alone a body carrying documents, then Clauss would surely hear of it. The German spy’s industriousness would be used against him. Later, if the operation worked, the proof of Clauss’s espionage activities would be so blatant that it could be used to ignite a diplomatic row, and, with luck, “sufficient evidence can be obtained

68

to get the Spaniards to eject him.” It was agreed: Huelva was the target, and if the unpleasant Clauss could be undermined, made to look a fool, and thrown out of Spain as a result, then so much the better.

A memo was sent to the Royal Navy’s hydrographer, the official repository of technical maritime information, with a veiled enquiry: if an object was dropped off the Spanish coast near Huelva, would the tides and prevailing winds bring it ashore? At the same time, Gómez-Beare was instructed to fly to Gibraltar and inform the flag officer there, and his staff officer in charge of intelligence, of the plan’s broad outlines. “They would have to

69

be in the picture,” Montagu explained, “in case the body or documents should by any chance find their way to Gibraltar.” Before returning to Madrid, Gómez-Beare should visit the British consuls at Seville, Cádiz, and Huelva and instruct them that the “washing ashore of any

70

body in their area was to be reported only to NA Madrid [naval attaché Alan Hillgarth] and to no other British authority.” Francis Haselden, the consul in Huelva, “was to be told the outline of the plan

71

without, of course, any description of its object.” Gómez-Beare should then return to Madrid and fully brief his boss.

Captain Alan Hillgarth would stage-manage the Spanish end of the operation, and there was no one better suited to the task.

CHAPTER NINE

My Dear Alex

E

VEN

C

HARLES

C

HOLMONDELEY’S

elastic mind was having trouble wrapping itself around the problem of how to transport a corpse from London to Spain and then drop it in the sea, without being spotted, in such a way that it would appear to be the victim of an air crash. There were, he reckoned, four possible methods of shipping Major Martin to his destination. The body could be transported aboard a surface ship, most easily on one of the naval escorts accompanying merchant vessels in and out of the Huelva port. This option was rejected, “owing to the need for placing

1

the body close inshore;” nothing was more likely to attract the attention of Adolf Clauss and his spies than a Royal Navy ship lingering in shallow waters. An alternative would be to take the body by plane and simply open the door and throw it out at the right spot. The problem, however, was that “if the body were dropped in this way

2

it might be smashed to pieces on landing,” particularly if it had already started to decompose. A seaplane, such as a Catalina, might be able to land, if the conditions were right, and slip the body into the water more gently. Cholmondeley drew up a possible scenario: the seaplane and its cargo would “come in from out at sea

3

simulating engine trouble, drop a bomb to simulate the crash, go out to sea as quickly as possible, return (as if it were a second flying boat) and drop a flare as if searching down the first aircraft, land, and then while ostensibly searching for survivors, drop the body etc, and then take off again.” On examination, this plan seemed far too elaborate. Any number of things could go wrong, including a real plane crash.

A submarine would be better. The drop could be carried out at night, and if there was insufficient depth of water, then a rubber dinghy could be used to take the body closer inshore. The submarine captain could monitor the winds and tides in order to surface and drop the body at the optimum moment. “After the body has been

4

planted it would help the illusion if a ‘set piece’ giving a flare and explosion with delayed action fuse could be left to give the impression of an aircraft crash.” The only problem, as Cholmondeley delicately put it, was the “technical difficulties in keeping

5

the body fresh during the passage.” Submariners were a notoriously hardy bunch, able to withstand long periods underwater in the most fetid and cramped conditions. But even submariners would surely object to having a rotting corpse as a shipmate. Moreover, the operation was top secret: the presence of a dead body on a submarine would not remain secret very long. “Of these methods,”

6

Cholmondeley concluded, “a submarine is the best (if the necessary preservation of the body can be achieved).”

There is no easy way to smuggle a dead body aboard a submarine, let alone prevent it from rotting in the warm, muggy atmosphere of a submarine hold. For help, Cholmondeley turned to Charles Fraser-Smith of “Q-Branch,” the chief supplier of gadgets to the Secret Service. A former missionary in Morocco, Fraser-Smith was officially a bureaucrat in the Ministry of Supply’s Clothing and Textile Unit; his real job was to furnish secret agents, saboteurs, and prisoners of war with an array of wartime gizmos, such as miniature cameras, invisible ink, hidden weaponry, and concealed compasses. Fraser-Smith provided Ian Fleming with equipment for some of his more outlandish plans, and he doubtless helped to inform the character of “Q,” the eccentric inventor in the James Bond films. Fraser-Smith possessed a wildly ingenious but supremely practical mind. He invented garlic-flavored chocolate to be consumed by agents parachuting into France in order that their breath should smell appropriately Gallic as soon as they landed; he made shoelaces containing a vicious steel garrote; he created a compass hidden in a button that unscrewed clockwise, based on the impeccable theory that the “unswerving logic of the German

7

mind” would never guess that something might unscrew the wrong way.

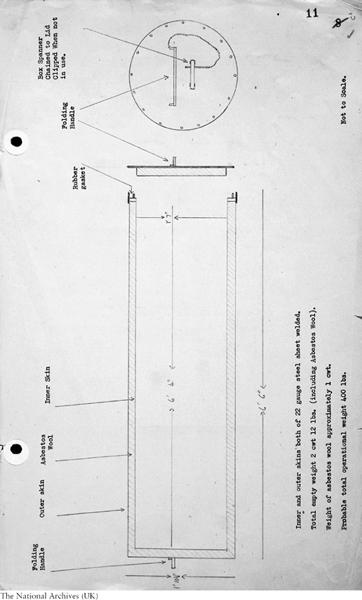

With the help of Fraser-Smith, Cholmondeley drew up a blueprint for the world’s first underwater corpse transporter. This was a tubular canister, six feet six inches long and almost two feet in diameter, with a double skin made from 22-gauge steel and the space between the skins packed with asbestos wool. One end would be welded closed, while the other had an airtight steel lid that screwed onto a rubber gasket with sixteen bolts. A folding handle was attached to either end, and a box wrench was clipped to the lid for easy removal. With the body inside, Cholmondeley estimated the entire package would weigh about four hundred pounds and would fit snugly into the pressure hull of a submarine. Sir Bernard Spilsbury was consulted once more. Oxygen, he explained, was the cause of rapid decomposition. But “if most of the oxygen had previously

8

been excluded” from the tube with dry ice, and if the canister was completely airtight, and if the body was carefully packed around with dry ice, then the corpse would “keep perfectly satisfactorily”

9

and remain as cold as it had been inside the morgue. Fraser-Smith’s task, then, was to design “an enormous Thermos flask”

10

thin enough to fit down the torpedo hatch. The Ministry of Aircraft Production was given the plans and instructed to build this container as fast as possible, without being told what it was for. On the outside of the canister should be stenciled the words

“HANDLE WITH CARE

11

—OPTICAL INSTRUMENTS—FOR SPECIAL FOS SHIPMENT.”