Operation Mincemeat: How a Dead Man and a Bizarre Plan Fooled the Nazis and Assured an Allied Victory (39 page)

Authors: Ben Macintyre

Tags: #General, #Psychology, #Europe, #History, #Great Britain, #20th Century, #Political Freedom & Security, #Intelligence, #Political Freedom & Security - Intelligence, #Political Science, #Espionage, #Modern, #World War, #1939-1945, #Military, #Italy, #Naval, #World War II, #Secret service, #Sicily (Italy), #Deception, #Military - World War II, #War, #History - Military, #Military - Naval, #Military - 20th century, #World War; 1939-1945, #Deception - Spain - Atlantic Coast - History - 20th century, #Naval History - World War II, #Ewen, #Military - Intelligence, #World War; 1939-1945 - Secret service - Great Britain, #Sicily (Italy) - History; Military - 20th century, #1939-1945 - Secret service - Great Britain, #Atlantic Coast (Spain), #1939-1945 - Spain - Atlantic Coast, #1939-1945 - Campaigns - Italy - Sicily, #Intelligence Operations, #Deception - Great Britain - History - 20th century, #Atlantic Coast (Spain) - History, #Montagu, #Atlantic Coast (Spain) - History; Military - 20th century, #Sicily (Italy) - History, #World War; 1939-1945 - Campaigns - Italy - Sicily, #Operation Mincemeat, #Montagu; Ewen, #World War; 1939-1945 - Spain - Atlantic Coast

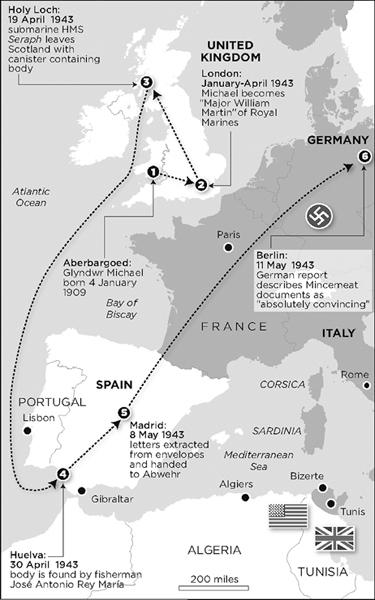

On May 12, the very day that Hillgarth reported the safe return of the briefcase, Juliette Ponsonby, the secretary of Section 17M, went to collect the latest Bletchley Park dispatches from the teleprinter room in the Admiralty. Montagu began leafing through the printouts and then suddenly uttered a loud whoop and banged the table so hard his coffee cup flew off the desk. That morning, the interceptors had picked up a wireless message sent by General Alfred Jodl, the OKW chief of the Operations Staff responsible for all strategic, executive, and war-operations planning, stating that “an enemy landing on a large scale

16

is projected in the near future in both the East and West Mediterranean.” The information, sent to the senior German commanders southeast and south, with copies to the Naval Staff Operations Division and Air Force Operations Staff, was described by Jodl as coming from “a source which may be regarded

17

as being absolutely reliable.” The message then furnished full details of the planned attack on Greece, precisely as described in Nye’s letter. Jodl himself gave his seal of approval to the documents: “It is very unusual for an intelligence

18

report to be passed on in operational traffic or by someone of [such] seniority with so high a recommendation of reliability,” wrote Montagu, who had studied thousands of such signals. “So far as I can recollect

19

it is almost unknown that such a thing should happen.”

The mood in the Admiralty basement changed instantly with the arrival of Most Secret Source message 2571. “Everyone jumped up and down.

20

We were so thrilled,” recalled Pat Trehearne. The ladies hugged one another. The gentlemen shook hands. The fly had been taken, and the tension seemed to vanish.

No corresponding message relating to the fake assault in the west on Sardinia was picked up, but the British concluded it was “almost certain”

21

that German commanders in the western theater had received by teleprinter “similar details from the letter

22

which concerned that area.” Jodl’s message was only the hors d’oeuvre. From this moment on, evidence steadily accumulated showing that “the Germans were reinforcing

23

our imaginary invasion areas in Greece … and at the same time spreading their available forces into Sardinia.” These were, in Montagu’s words, “wonderful days.”

24

Winston Churchill was in Washington for the war conference code-named “Trident,” working on plans with Roosevelt for the invasion of Italy, the bombing of Germany, and the Pacific war. A telegram was immediately dispatched to the prime minister, stating cryptically that Mincemeat had reached “the right people and from best

25

information they look like acting on it.”

Cholmondeley was quietly jubilant. Montagu scribbled a celebratory note on a postcard and sent it to Bill Jewell of HMS

Seraph:

“You will be pleased to learn

26

that the Major is now very comfortable.” He also wrote to Iris in New York: “Friday was almost too good

27

to be true. I had marvellous news of the success of a job that I was doing (it was so good that I feel a snag must arise).” Montagu was deeply relieved, yet he remained cautious, knowing that the deception was still at an early stage. The Abwehr in Madrid had fallen for the hoax, and so, it seemed, had the intelligence analysts in Berlin. The initial messages, wrote Montagu, “proved that we had convinced them.

28

Now would they convince the general staff?”

He had no cause to fret, for back in Germany the Mincemeat lie was building up steam. On the day Jodl’s cable was sent to Germany’s Mediterranean commanders, Hans-Heinrich Dieckhoff, the German ambassador in Madrid, sent a telegram to the Foreign Office in Berlin: “According to information

29

just received from a wholly reliable source, the English and Americans will launch their big attack on Southern Europe in the next fortnight. The plan, as our informant was able to establish from English secret documents, is to launch two sham attacks on Sicily and the Dodecanese, while the real offensive is directed in two main thrusts against Crete and the Peloponnese.” Dieckhoff was clearly writing without the benefit of von Roenne’s analysis, for he missed the reference to Sardinia. An hour later, Dieckhoff sent another message, reporting that Francisco Gómez-Jordana y Souza, the Spanish foreign minister, had told him “in strict confidence”

30

that Allied attacks should be expected in Greece and the western Mediterranean. The secret was now streaming through the upper echelons of the Spanish government and being fed back to the Germans. “Jordana begged me not to

31

mention his name,” reported Dieckhoff, “especially as he wanted

32

to exchange further information with me in the future. He considered the information wholly trustworthy, and felt it his duty to pass it on.”

The Mincemeat letters were now, finally, homing in on the ultimate target. Three weeks and three thousand miles after their journey began, the forgeries finally landed on the desk of the man for whose eyes they had always been intended, the only person whose opinion really mattered.

Adolf Hitler’s initial response was skeptical. Turning to General Eckhardt Christian, the Luftwaffe chief of staff, he remarked: “Christian, couldn’t this be a corpse

33

they have deliberately planted on our hands?” General Christian’s response is not recorded, and by May 12, the day after von Roenne’s enthusiastic report, any doubts in Hitler’s mind had evaporated. That day, the Führer issued a general military directive: “It is to be expected that

34

the Anglo-Americans will try to continue the operations in the Mediterranean in quick succession. The following are most endangered: in the Western Med, Sardinia, Corsica and Sicily; in the Eastern Med, the Peloponnese and the Dodecanese. … Measures regarding Sardinia and the Peloponnese take precedence over everything else.” The orders reflected a dramatic shift in priorities since, as Montagu observed, “the original German appreciation

35

had been that Sicily was more likely to be invaded than Sardinia.” Sicily now appeared to be, in German thinking, the least vulnerable of the Mediterranean islands, with the focus firmly trained on Greece and Sardinia. Hitler ordered “all German commands

36

in the Mediterranean to utilise all forces and equipment to strengthen as much as possible the defences of these particularly endangered areas during the short time which is probably left to us.”

In Washington D.C., Roosevelt and Churchill were hammering out the next stage of the war, looking beyond Operation Husky. “Where do we go from Sicily?”

37

the president asked. The Americans favored assembling a mighty army in Britain to attack across the Channel as soon as possible. Churchill and his advisers preferred an invasion of the Italian mainland itself, disemboweling the soft underbelly. “The main task which lies before us,”

38

the British argued, “is the elimination of Italy”—this would force Hitler to divert troops from elsewhere and undermine German strength on both the eastern and western fronts. After three days in the presidential retreat in the mountains of Maryland, later named Camp David, Churchill addressed a joint session of Congress: “War is full of mysteries and surprises,”

39

he said. “By singleness of purpose, by steadfastness of conduct, by tenacity and endurance—such as we have so far displayed—by this and only this can we discharge our duty to the future of the world and to the destiny of man.” The Anglo-American conference broke up with the agreement that Eisenhower would continue the fight in the south of Europe, while a great cross-Channel offensive would be prepared for the following May. But first, Sicily.

At the press conference ending the Trident meeting, Churchill was asked: “What do you think is going

40

on in Hitler’s mind?” There was laughter, and Churchill replied: “Appetite unbridled.

41

Ambition unmeasured—all the world!” Secretly, Churchill now knew that in one corner of Hitler’s mind, another conviction had settled: that the Allied armies in North Africa were aiming at Greece in the east and Sardinia in the west, while Sicily would be left alone.

With the effects of Operation Mincemeat appearing in intercepted German messages, Montagu raised a security issue. If someone outside the secret saw reports referring “to a document that had been

42

captured from a dead body” there would be a serious “security flap,”

43

and questions would be asked about why top secret documents had been carried abroad in this way, in defiance of wartime regulations. Bletchley Park had been instructed to ensure that any messages referring to the intercepted Mincemeat documents were initially sent only to “C,” the head of MI6, and to Montagu himself. “Arrangements could then be made

44

to warn recipients or to limit the distribution.”

Von Roenne had chosen to accept the documents at face value, and his analysis was now hurtling up the German power structure. Not everyone was entirely convinced. Major Percy Ernst Schramm, who kept the OKW war diary, recalled the intense discussion among senior officers over whether the letters might be forged: “We earnestly debated

45

the question ‘Genuine or not? Perhaps genuine? Corsica, Sardinia, Sicily, the Peloponnese?’ ” On May 13, a skeptical officer at FHW in Zossen, identified by the code name “Erizo,” sent a message to the Abwehr in Madrid demanding more details about the discovery of the documents. “The evaluation office attach special

46

importance to a more detailed statement of the circumstances under which the material was found. Particular points of interest are, when the body was washed ashore, when and where the crash is presumed to have taken place. Whether aircraft and further bodies were observed, and other details. Urgent Reply by W/T [wireless] if necessary.”

German analysts had now spent several days studying the letters and the accompanying reports. The demand for greater detail on the discovery suggests that the inconsistency between the postmortem, indicating at least eight days of decomposition, and Kühlenthal’s timing of just three days between crash and discovery had not gone unnoticed. The FHW also appears to have questioned how a decomposing corpse at sea for more than a week could still be holding a full briefcase when it reached the shore. And if a plane had crashed in the Mediterranean, where was the wreckage? The cable was followed by a telephone call from FHW, again pressing for more details.

The Madrid Abwehr office replied, somewhat huffily, that it had already requested, four days earlier, a detailed report on the discovery from the Spanish General Staff: “The latter immediately despatched

47

an officer to the spot. The results of the officer’s findings partly differ in detail from the facts of the case as first represented by the General Staff. Detailed report will arrive at Tempelhof [airport in Berlin] on evening of 15/5. Have it collected.”

Kühlenthal had clearly picked up the new note of skepticism in Berlin, and, as he always did when under pressure, he simultaneously covered his back and passed the buck: “Oberst Lt. Pardo on the 10th May,

48

was emphatic that the answers he gave us were a complete story of the whole affair without reservations, but it seems, however, that this was not so.” The Spanish officer sent by the General Staff to Huelva to find out more about the discovery of the body and the papers had now returned to Madrid. “The result of his investigations

49

was communicated to us this morning in the presence of Oberst Lt. Pardo’s commanding officer.”