Oral Literature in Africa (48 page)

Read Oral Literature in Africa Online

Authors: Ruth Finnegan

It is hard

To bring unbelievers

Into the brotherhood of believers.

But we need the die-hards

To spur us on

To make life complete.

(Schachter 1958: 677)

or in compositions by the women:

Here is the light

Of the chieftaincy of Sékou Touré.

It rises,

Inextinguishable,

Immeasurable,

Glorious.

Those who are of good faith

Speak in our way.

Those who are of bad faith

Qualify what they say.

One single thing is true.

When the sun rises

The palm of the hand

Cannot hide its light.

It is visible;

It is gigantic.

You cannot stand its heat.

Even in a shaded place.

It is like the light

Of Sékou’s chieftaincy.

(Ibid.: 675–7)

So effective was this R.D.A. mass opposition that the administration was forced to reconsider its policy and the French Colonial Minister came out to explore the possibility of a different approach. The R.D.A. seized the opportunity to demonstrate its wide support and turned out huge crowds in welcome. R.D.A. militants took charge of public order, giant placards were paraded, and R.D.A. songs were performed all the way along the route from the airport to the town.

This visit marked the turning point. Though popular protests continued, the R.D.A. considered it a confession of their success and of the metropolitan

French government’s repudiation of the local administration’s policy. More elections were finally held in January 1956 (and yet more songs were composed). The R.D.A.’s candidates, including Sékou Touré, won two of the three Guinea seats to the French National Assembly. This final triumph was summed up in their songs of triumph over their now powerless opponents. They sang:

You prepare food,

The most exquisite food to be found.

You are ready with your spoon

To spoon out the first spoonful.

And lo! a drop of violent poison

Falls into the food.

The water is dirtied

It becomes undrinkable.

All is finished.

All is over.

(Schachter 1958: 681)

The campaign had finally been successful and the propaganda had fulfilled its purpose.

By the late 1950s and early 1960s political songs in Africa seem to have become a standard accompaniment of recognized political parties and the election campaigns that were by now becoming more and more a feature of political activity in African colonies and ex-colonies. Songs formed part of election campaigns in, for example, Sierra Leone and Senegal in 1957, Nyasaland in 1961, and Northern Rhodesia in 1962. Some politicians managed to exploit oral propaganda even further and, like the Western Nigerian leader Adelabu, organized the circulation of gramophone records of songs supporting them (Sklar 1953: 300; 313).

12

Altogether there is still great reliance on oral means of propaganda—speeches, mass meetings, and songs—in keeping with the still largely non-literate or semi-literate mass electorate for whom the written word is of relatively lesser significance.

Northern Rhodesia (later Zambia) seems to have been particularly rich in organized political songs in the vernacular, sometimes specially composed and written for the party, and often sung by official mass choirs. Several have been published among those written for the African National

Congress (A.N.C.) in the late 1950s. One, cast in the form of a praise song, honouring Nkumbula, President of the A.N.C., had the familiar purpose of attempting to project a leader’s image to the mass of followers:

Mr. Nkumbula, we praise you.

You have done a good work.

Look today, we sing praising you,

For you have done a good work.

We praise, too, all your cabinet

And all your Action Group.

You have done good work.

(Rhodes 1962: 18)

Two other songs can be quoted that were used to promote the A.N.C.’s policies and to educate as well as incite the masses. Ill-defined popular grievances are taken up and focused into definite political aims associated with the party programme. The first is in the form of a meditation with chorus, suitable for the whole audience to echo:

One day, I stood by the road side.

I saw cars passing by.

As I looked inside the cars

I saw only white faces in them.

These were European settlers.

Following the cars were cyclists

With black faces.

They were poor Africans.

Refrain

. The Africans say,

Give us, give us cars, too,

Give us, give us our land

That we may rule ourselves.

I stood still but thinking

How and why it is that white faces

Travel by car while black faces travel by cycle.

At last I found out that it was that house,

The Parliamentary House that is composed of Europeans,

In other words, because this country is ruled by

White faces, these white faces do not want

Anything good for black faces.

(Ibid.: 19)

Sharp political comment and demand can also be conveyed:

When talking about democracy [the English word]

We must teach these Europeans

Because they do not know.

See here in Africa they bring their clothes

But leave democracy in Europe.

Refrain

. Go back, go back and

Bring true democracy.

We are no longer asleep

We are up and about democracy

We have known for a long time.

We are the majority and we demand

A majority in the Legislative Council.

(Rhodes 1962: 20)

How far removed these songs are from the Mau Mau emphasis on secrecy can be seen from the fact that a few of these A.N.C. songs are in fact in English—a way of applying pressure on Europeans.

The open and public nature of Northern Rhodesian party songs also comes out in the election campaign fought in 1962. Songs, usually in Bemba, were a recognized part of mass meetings. Mulford describes a typical rally:

Thousands were packed in an enormous semi-circle around the large official platform constructed by the youth brigade on one of the huge ant hills. Other ant hills nearby swarmed with observers seeking a better view of the speakers. Hundreds of small flags in UNIP’s colours were strung above the crowd. Youth brigade members, known as ‘Zambia policemen’ and wearing lion skin hats, acted as stewards and controlled the crowds when party officials arrived or departed. UNIP’S jazz band played an occasional calypso or jive tune, and between each speech, small choirs sang political songs praising UNIP and its leaders.

Kaunda will politically get Africans freed from the English,

Who treat us unfairly and beat us daily.

UNIP as an organization does not stay in one place.

It moves to various kinds of places and peoples,

Letting them know the difficulties with which we are faced.

These whites are only paving the way for us,

So that we come and rule ourselves smoothly.

(Mulford 1964: 133–4)

These UNIP songs were not confined to statements of policy and aspiration (‘These whites are only paving the way for us …’), but also sometimes gave precise instructions for the actual voting, a matter of great importance in campaigns among an inexperienced electorate. One particularly infectious calypso sung in English gave the necessary instructions:

Upper roll voting papers will be green.

Lower roll voting papers will be pink.

Chorus

. Green paper goes in green box.

Pink paper goes in pink box.

(Ibid.: 134–5)

These three examples of the use of political songs, drawn from very different political situations, show something of the flexibility of this particular

medium. Songs can be used to veil a political message from opponents, to publicize it yet further, to whip up popular support, or to pressurize its enemies. In different contexts, songs can have the effect of intensifying factional differences, or of encouraging national unity.

13

They can focus interest on the image of the leader (or of the opponent) and on the specific political aims of the party. Their effectiveness in reaching mass audiences in countries without a tradition of written communication cannot be exaggerated. Songs can be picked up and learnt by heart, transmitted orally from group to group, form a real and a symbolic link between educated leader and uneducated masses—in short, perform all the familiar functions of political propaganda and comment.

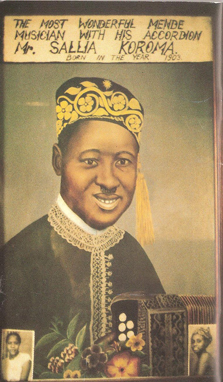

Figure 19. ‘The Most Wonderful Mende Musician with his Accordion’: Mr Salla Koroma, Sierra Leone.

Little has been written about the literary quality and form of these political songs; most of them have been collected by those interested primarily in their political content. But it does not necessarily follow that, just because they have a clear political function, there are therefore no artistic conventions observed by composer or singers, or that they can necessarily be dismissed as of no serious artistic interest. It seems that in some cases the songs are based on traditional literary forms of one kind or another. Praise of political leaders fits with the traditional interest in panegyric

14

and among some peoples (e.g. Kikuyu or Ndebele) old war songs are sometimes used in new contexts for political pressure or intimidation (Leakey 1954: 56;

Afr. Music

2.4, 1961: 117) while among the Somali the traditional and serious

gabay

form is now commonly used for political propaganda (Andrzejewski and Lewis 1964: 48). In other cases one of the dominant models would seem to be that of the Christian hymn, an influence apparent not only in the case of Mau Mau but also, among others, with the C.P.P. in Ghana or the Nigerian N.C.N.C. (see e.g. Hodgkin 1961: 136). But how far the artistic conventions of the originals are carried over into the political adaptations is by no means clear.

What does appear certain is that there will remain plenty of opportunity to study the literary quality of the songs, for they show no signs of dying out. Indeed their contemporary relevance is demonstrated—if demonstration is needed—in the action of the Nigerian military rulers in 1966 in banning political songs as part of their attempt to curb political activity, or the Tanzanian government’s appeal to musicians in 1967 to help to spread its new policies of socialism and self-reliance to the people through song. It is too easy to assume that this means of oral propaganda is bound to disappear with increasing literacy and ‘modernization’, as if newspapers and written communications were somehow the only ‘natural’ and ‘modern’ way of conducting political propaganda. On the contrary it is possible that the spread of the transistor radio may in fact add fresh impetus to political songs.

Figure 20. Radio. Topical and political songs, already strong in Africa, receive yet further encouragement by the ubiquitous presence of local radio (courtesy of Morag Grant).

Footnotes

1

For a useful general account and bibliography, not specifically related to Africa, see Denisoff 1966.

2

For an interesting description of Swahili political songs and lampoons in the nineteenth century see Hinawy 1950: 33ff.

3

Paramount chief of the district.

4

Local xylophone.

5

Folkways Records Album EPC-601, New York, quoted Rhodes 1962: 22.

6

For other instances of topical songs see D.C. Simmons (1960); J. Roberts (1965); Ogunba (1967).

7

The present account is taken from the description in L.S.B. Leakey,

Defeating Mau Mau

, London 1954, esp. Ch. 5.

8

The traditional ‘Eve’ of the Kikuyu.

9

This means that when members of Mau Mau (who always refer to themselves as the house of Mumbi) meet for an oath ceremony at which others are formally enlisted into the movement, there are some who go and report to the police and take on themselves the role of traitor.