Oral Literature in Africa (62 page)

Read Oral Literature in Africa Online

Authors: Ruth Finnegan

These songs fulfil various functions in the narrative. They often mark the structure of the story in a clear and attractive way. Thus, if the hero is presented as going through a series of tests or adventures, the parallel presentation of episode after episode is often cut into by the singing of a song by narrator and audience. Further, the occurrence of songs adds a musical aspect—an extra dimension of both enjoyment and skill. In some areas (particularly parts of West and West Equatorial Africa) this musical element is further enhanced by drum or instrumental accompaniment or prelude to the narration.

74

The songs also provide a formalized means for audience participation. The common pattern is for the words of the song, whether familiar or new, to be introduced by the narrator, who then acts as leader and soloist while the audience provide the chorus.

Having discussed the significance of the actual performance of stories, we can raise the question of the individual contributions of the various narrators. Even if there are conventionally recognized ways of enhancing delivery, the narrator can exploit these and, in the last analysis, is responsible for all the aspects of performance already mentioned. It is evident then that one way of discovering the extent of the individual artistry involved in the narration of African stories is through the investigation of individual narrators’ relevant skills and idiosyncrasies.

Composition as well as performance is involved. The narrator of a story is likely to introduce his own favourite tricks of verbal style and presentation and to be influenced in his wording by the audience and occasion; thus he will produce linguistic variations on the basic theme different from those of his fellows or even from his own on a different occasion. In addition to this, there is the individual treatment of the various incidents, characters, and motifs; these do not emerge when only one version of the story appears in published form. Finally, there are the occasions when, in a sense, a ‘new’ story is created. Episodes, motifs, conventional characters, stylistic devices which are already part of the conventional literary background on which the individual artist can draw are bound together and presented in an original and individual way.

This

real

originality, as it appears to the foreigner, is really only a difference in degree, for there is seldom any concept of a ‘correct’ version.

In all respects the narrator is free to choose his own treatment and most stories arise from the combination and recombination of motifs and episodes with which the individual is free to build. Stories are thus capable of infinite expansion, variation, and embroidery by narrators, as they are sewn together in one man’s imagination.

75

The subject-matter too on which such artists draw is by no means fixed, and the common picture of a strict adherence to ‘traditional’ and unchanging themes is quite false. Not only are there multiple references to obviously recent material introductions—like guns, money, books, lorries, horse-racing, new buildings—but the whole plot of a story can centre round an episode like an imaginary race to the Secretariat building in a colonial capital to gain government recognition for an official position (Limba), a man going off to get work in Johannesburg and leaving his wife to get into trouble at home (Thonga), or a young hero winning the football pools (Nigeria). The occupations and preoccupations of both present and past, the background of local and changing literary conventions, and the current interests of both teller and listeners—all these make up the material on which the gifted narrator can draw and subject to the originality of his own inspiration.

The question of the originality of the individual teller, whether in performance or composition, is one of the most neglected aspects of African oral narratives. That so obvious a point of interest should have been overlooked can be related to various constricting theoretical presuppositions about African oral art that have been dominant in the past: the assumption about the significance of the collective aspect, i.e. the contribution by ‘the folk’ or the masses rather than the individual; the desire to find and record

the

traditional tribal story, with no interest in variant or individual forms; and, finally, the prejudice in favour of the ‘traditional’, with its resultant picture of African oral art as static and unchanging through the years and the consequent explicit avoidance of ‘new’ or ‘intrusive’ stories. It is worth stressing here yet again that the neglect of this kind of point, one which seems so self-evidently a question to pursue in the case of any genre of literature, is

not

primarily due to any basis in the facts or to any proven lack of originality by African literary artists, but to this theoretical background of by now very dubious assumptions. Now that the dominance of many of

these theories is passing, at least in some circles, it is to be trusted that far more attention will be paid to this question of authorship and originality in African oral literature.

Figure 22. ‘Great Zimbabwe’, the spectacular ruins in the south of the modern Zimbabwe, 1964 (photo David Murray). The ruins were believed by earlier European settlers and scholars to have been built by the Phoenicians, Carthaginians, or lost tribe of Israel (anyone other than Africans); or, by more comparatively-minded historians to parallel the Athenian acropolis; by more recent historians held to have been constructed during the African kingdoms of the eleventh to fourteenth centuries. In one version or another is now incorporated into established African mythology (for further comment see

wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Zimbabwe

).

This final section on the various aspects of oral prose narratives which, hitherto neglected, now demand further emphasis has had one underlying theme. That is, that the many questions that we would normally expect to pursue in the analysis of any literary genre should also be followed up in the case of these African stories. That this obvious approach has tended to be obscured is largely due to the limiting theoretical assumptions of the past that were discussed earlier. The stories are in fact far more flexible, adaptable, and subtle than would appear from the many traditionally-orientated published collections and accounts; if certain types and themes are dying out, others are arising, with new contexts and themes that provide a fruitful field of study. Once we can free our appreciation of past speculations, we can see these stories as literary forms in their own right. While some of the questions such as the significance of occasion, of delivery, or of audience participation, arise from their

oral

nature, others, such as the literary and social conventions of a particular literary form, its purpose and functions, and the varying interpretations of individual artists, are the traditional questions of literary analysis. These aspects concern both the literary scholar and the sociologist who want to understand the at once subtle and significant role of literature in a given society, and their study would seem to provide the greatest potential for further advance in our knowledge of African oral prose narratives.

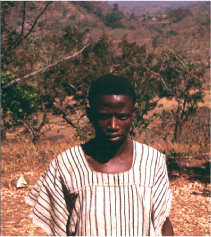

Figure 23. Karanke Dema, master story-teller, drummer, musician and smith Kakarima, 1961 (photo Ruth Finnegan).

Footnotes

1

The question of the total number of African stories is sometimes canvassed. Numbers like 5,000, 7,000, or (for unrecorded as well as recorded tales) even 200,000 have been mentioned (Herskovits 1960 (1946): 443–4). But this is hardly a fruitful question; it is not even in principle possible to count up items of oral art when it is the actual narration that matters and there are thus an infinite number of ways in which the ‘same’ plot can be presented and varied to become a ‘new’ and unique narration. Similarly, those who aim at the complete recording of all the oral literature of a given people—’every little bit of this vernacular’, as Mbiti for one hopes (Mbiti 1959: 253)—are setting themselves an impossible goal.

2

e.g. Herskovits’s Dahomean stories that were apparently first translated (during the actual flow of the story) from Fon into French by local interpreters, taken down on typewriters by the Herskovitses, and finally published in English (see Herskovits 1958: 6). How much of the indefinable literary qualities of the stories could survive such treatment can be left to the reader to imagine.

3

And not just from Bantu Africa as sometimes suggested.

4

e.g. Berry 1961; Lindblom 1928 (see ‘comparative notes’ in vols, i and ii); Herskovits 1960 (1946) and Herskovits 1936; Wright 1960 (a short and specialized but useful article); Werner 1933 (Bantu). Also (unpublished) Mofokeng 1955; Klipple 1938; Clarke 1958.

5

The actual instances cited are from the Hottentot, Kgatla, Yao, Tetela, Limba, and Ghana—i.e. from South, Central and West Africa respectively. For further instances see Klipple 1938: pp. 178ff.

6

On the distribution of this plot see e.g. Werner 1960: 249; Berry 1961: 10; Klipple 1938: 490ff.

7

See among other sources Abrahamsson 1951, esp. Ch. 2; Klipple 1938: 755ff.

8

Klipple 1938: 688ff. Examples and discussion of other variants of the accumulation or

ritornelle

story in Africa are given in Werner 1923; cf also Berry 1961: 9.

9

Recorded on tape from the public telling of the story in February 1961 and given here in a fairly close translation. The original text is given in R. Finnegan,

The Limba of Sierra Leone

, D.Phil, thesis, University of Oxford, 1963, iii: 488–9.

10

The speaker, apparently by mistake, interpolated a few sentences about the hen which should clearly have come later and are omitted. This particular narrator was by no means distinguished as a story-teller.

11

The finch, like the hen earlier, goes to pick among the grain.

12

This was clear in the actual narration, though not in the words.

13

The finch ‘proves’ that the hen is his property by showing that his nest is lined with hen’s feathers for his children to sleep on.

14

The same general framework is used in several other Limba stories, e.g. two included in Finnegan 1967: 334–6.

15

See e.g. Finnegan 1967: 93ff. and 347ff, for instances of the effects of different narrators and occasions among the Limba; and Evans-Pritchard 1964 for versions of the ‘same’ story among the Azande.

16

For further references see p. 336 n. 3. On plots in Bantu stories, see especially Werner 1933.

17

Cagnolo 1952–53; Evans-Pritchard 1967: 23 (and cf. Kronenberg 1960: 237, on characters in Nilotic tales); Krige 1936: 346 (cf. Jacottet 1908: xxvii).

18

On the hare, see Frobenius 1923: 131.

19

On the distribution of spider stories see, among other accounts, V. Maes, ‘De Spin’,

Aequatoria

13, 1950.

20

On the jackal, see Bleek 1864, part I; Jacottet 1908, p. xxvii. The jackal may also occur in stories in some northerly areas of Africa, but the older assumptions, which saw this as part of a wider scheme in which the jackal was the typical trickster among the so-called ‘Hamites’ (supposed to cover Hottentots as well as certain North Africans), are no longer tenable, and the significance of the jackal in the north may have been exaggerated to fit the theory.

21

e.g. among the Kalahari. See the analysis of this in Horton 1967.

22

This is pointed out by W. James in her unpublished B.Litt. thesis,

Animal Representations and their Social Significance, with Special Reference to Reptiles and Carnivores among Peoples of Eastern Africa

, Oxford, 1964: 215.

23

Even clearer instances of the sometimes peripheral nature of aetiological conclusions is provided by Limba stories where, even in the ‘same’ plot, an explanation sometimes appears, sometimes not.

24

e.g. in Acholi and Lango tales where the story is ostensibly about, say, the hare, or ‘a certain man’, and set in the past, but is in fact designed to ridicule someone who is present (Okot 1963: 394–5).

25

A point brought out in Evans-Pritchard’s account of the Zande trickster (Evans-Pritchard 1967: 28–30).