Authors: Kim van Alkemade

Orphan #8 (44 page)

Fannie and Victor at the Hebrew Orphan Asylum

. Photograph from author’s collection.

I asked if I might meet him in New York for an interview and he was delighted at the prospect. Together we toured Jacob Schiff Playground, the public park on Amsterdam Avenue where the massive orphanage once stood. Much of my fictional depiction of life in the Orphaned Hebrews Home was inspired by Hy’s words and memories. Thanks to him, I was able to imagine Rachel’s life in the orphanage, from clubs and dances to loneliness and bullying.

My research suggests that my grandfather Victor flourished at the Hebrew Orphan Asylum. By the time he was a high school senior, he was a salaried captain—a position just below counselor—as well as vice-president of the Boys’ Council, a member of the Masquerade Committee, secretary of the Blue Serpent Society, and a member of the varsity basketball team. He was “the hustling young business manager” for

The Rising Bell

, the orphanage’s monthly magazine. Upon his graduation from DeWitt Clinton School, Vic was praised for his “stick-to-it-iveness” and “pleasant personality.” A “brilliant future in the outside world” was predicted for this “ever-efficient boy of the Home.” Though he rarely spoke of his childhood in the orphanage, he did express his gratitude for the institution in which he lived from age 6 to 17.

But I knew there was another side to Victor’s childhood memories. In 1987, my dad had gone missing; for two months,

we’d had no inkling of his whereabouts. When Victor said, “I want to talk to you about your father,” I was expecting the same optimistic platitudes I’d been hearing for weeks: that everything would turn out fine, how brave I was, how strong. I couldn’t have been more mistaken. “Your father left you. You just forget about him from now on.” I knew Victor’s attitude was misplaced—if we were sure of anything, it was that my dad hadn’t run away to start a new life somewhere else—but my grandfather had gotten my attention. “My father left us, too, when me and my brothers, your uncles Seymour and Charles, were just little boys.” I understood now. Victor was offering me advice, one orphan to another, on how a child gets through life without a father: just forget about him.

“We got a letter from my father once, did you know that?” This was news to me. I’d always assumed my great-grandfather had

vanished, whereabouts unknown. Until I started researching my family history, I didn’t even know his name. “When your Grandma Fannie worked at the Reception House in the orphanage, we used to visit her on Sundays, me and my brothers. One time, she read us this letter she’d gotten from California, that our father was sick and would we send money for his treatment. She asked us boys what should she do. We told her not to send him a dime. A few months later she got another letter saying that he died, and would we send money for a headstone. Me and my brothers, we said no. He left us, like your dad left you. We didn’t owe him a thing, and neither do you. Remember that.”

The dining room in the Orphaned Hebrews Home, where the Purim Dance was held, was inspired by this photograph of Thanksgiving dinner at the Hebrew Orphan Asylum

. Courtesy of The New York Academy of Medicine Library.

What amazed me more than the revelation of the letters was Victor’s anger. It radiated off him, like heat rising over asphalt. Seventy years had elapsed and still he was mad at his father for making him an orphan. In April, the melting snows would expose my father’s body, revealing that I was the daughter of a suicide, the outcome I’d suspected all along. Surely, that was different from

the way Harry Berger had left his family? But however they left us, Victor and I were both children abandoned by their fathers.

This picture shows patients suffering from tuberculosis being treated with heliotherapy at the Jewish Consumptives’ Relief Society, my inspiration for the Hospital for Consumptive Hebrews

. Courtesy of the Beck Archives, Special Collections, CJS and University Libraries, University of Denver.

Instead of following my grandfather’s advice to forget, however, I became intensely curious to know more. I began researching my family history, learning all I could about Harry Berger, the man who left his wife, forcing her to commit their sons to the Hebrew Orphan Asylum. Eventually, that research led to the discoveries that inspired me to write

Orphan #8

.

Conditions among Animals

The question that remained was about the woman who had conducted the X-ray treatments that left the children bald. Dr. Mildred Solomon is a completely imaginary character, unlike her counterpart in the novel, Dr. Hess. He was inspired by the real Dr. Alfred Fabian Hess, who was an attending physician at the Hebrew Infant Asylum during the years in which my novel is set, and where he conducted research into childhood nutritional diseases, including rickets and scurvy. His infant isolation ward

was lauded in a 1914 article in the

New York Times

, which stated that “the great advantage of the glass walls” was that “neither nurse nor doctor need pay many visits to the children under their care.”

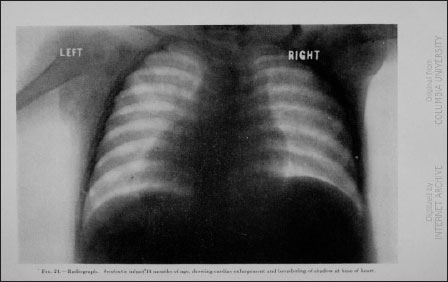

An X-ray of a 14-month-old baby with scurvy and an enlarged heart, from

Scurvy: Past and Present

by Dr. Alfred Hess (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1920)

.

In the novel, my character’s dialogue is inspired by the real Dr. Hess’s own writing; in fact, the long passage Rachel reads in the medical library is a direct quote. And yes, he was married to the daughter of Isidor and Ida Strauss, who went down on the Titanic.

The real Dr. Hess was often assisted by Miss Mildred Fish, coauthor on some of his nutrition studies and my inspiration, along with Dr. Elsie Fox, for Dr. Solomon. My research took me to the New York Academy of Medicine, where I began to understand my character of Mildred Solomon more fully—the struggles she would have gone through, the pressures she was under, the goals to which she aspired. Dr. Solomon’s confrontation with Rachel gives the elderly woman a chance to defend her life’s work and her actions.

In the early twentieth century, the medical field was becoming

more scientific, and research became increasingly privileged. Amazing discoveries seemed to justify whatever methods were necessary to achieve the miraculous vaccinations and treatments that conquered disease and relegated conditions, such as rickets and scurvy, to the pages of American history. Today, the ethics of many such experiments have been condemned: the testing of the polio vaccine on children in an orphanage; the study of untreated syphilis in prisoners; the sterilization of people who are impoverished or intellectually disabled. Sadly, disenfranchised people have often been “material” for medical experimentation.

A ward at the Hebrew Infant Asylum, circa 1908

. Courtesy of The New York Academy of Medicine Library.

It seems impossible now, however, to look back on experiments like those conducted by Dr. Fox and Dr. Hess and not see them through the distorting lens of the Holocaust. When telling people what

Orphan #8

is about, I have learned that saying the words “Jewish children” and “medical experiments” in the same sentence is almost guaranteed to elicit a remark about Nazis. It seemed inevitable that Rachel herself, looking back on her childhood, would draw the same comparison, and only fair to allow Dr. Solomon to defend herself from these charges.

A Wall They Cannot See

Joan Nestle, cofounder of the Lesbian Herstory Archives, came to Milwaukee to give a lecture while I was in graduate school there. She read to us from a letter given to the archives by a woman who had endured the humiliation and fear of a police raid on a lesbian club in the 1950s. When I imagined Rachel and Naomi’s relationship, at first I thought no further than their romantic reunion at the carousel. But as I developed the novel, I realized how important it was to explore the ways in which the characters would have responded to the repressive era in which they lived. As a lesbian writing at the time explained, “Between you and other women friends is a wall which they cannot see, but which is terribly apparent to you. The inability to present an honest face to those you know eventually develops a certain deviousness which is injurious to whatever basic character you may possess. Always pretending to be something you are not, moral laws lose their significance.”

In the 1950s, psychiatry in America purported that

homosexuality was a psychological disorder that could be cured through analysis and therapy. The prevailing scientific view, as expressed by Dr. Frank Caprio in

Female Homosexuality: A Psychodynamic Study of Lesbianism

(New York: Citadel Press, 1954), was that homosexuality resulted from “a deep-seated and unresolved neurosis.” Caprio explained, “Many lesbians claim that they are happy and experience no conflict about their homosexuality, simply because they have accepted the fact that they are lesbians and will continue to live a lesbian type of existence. But this is only a surface or pseudohappiness. Basically, they are lonely and unhappy and are afraid to admit it, deluding themselves into believing that they are free of all mental conflicts and are well adjusted to their homosexuality.”