Oswald and the CIA: The Documented Truth About the Unknown Relationship Between the U.S. Government and the Alleged Killer of JFK (66 page)

Authors: John Newman

That question needs to be answered. We know that when the Protective Research Section of the Secret Service put together their list of dangerous persons in the Dallas-Fort Worth area, Oswald's name was not on it.' We need a fuller discussion of why it was not, but such a discussion seems pointless without first putting all the facts on the table. The potential magnitude of the problem and the possible corrective measures that may be indicated are too important to put off until the next century.

The foregoing is only a first look at the internal record of Oswald since the government began releasing files in accordance with the JFK Assassination Records Act. Of the many riddles we have attempted to solve in this book, the Dealey Plaza puzzle is not among them. The author lacks the requisite skills in ballistics, forensic pathology, photo and imagery interpretation, and criminal psychology, to name but a few. We need fewer studies that claim to have all the answers and more that focus on specific areas and are built on firm robust evidentiary foundations. The fact that the public has made several inaccurate guesses does not mean that their suspicions about the Warren Commission conclusions are not justified.

What Does This Do for the Case?

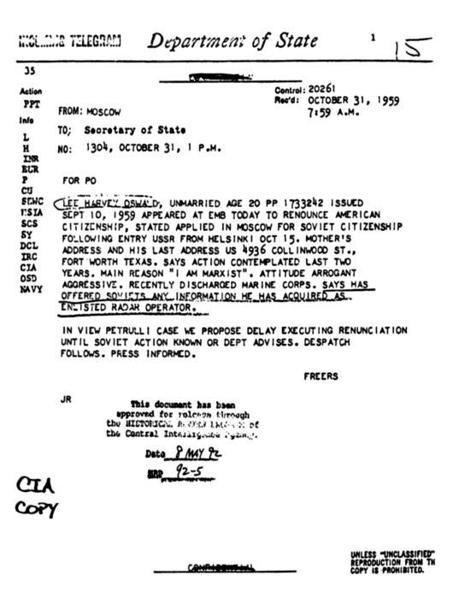

The CIA was far more interested in Oswald than they have ever admitted to publicly. At some time before the Kennedy assassination, the Cuban affairs offices at the CIA developed a keen operational interest in him. Oswald's visit to Mexico City may have had some connection to the CIA or FBI. It appears that the Mexico City station wrapped its own operation around Oswald's consular visits there. Whether or not Oswald understood what was going on is less clear than the probability that something operational was happening in conjunction with his visit.

While we are unclear on the precise reasons for the CIA's pre-assassination withholding of information on Oswald, we have yet to find documentary evidence for an institutional plot in the CIA to murder the president. The facts do not compel such a conclusion. If there had been such a plot, many of the documents we are reading-such as the CIA cables to Mexico City, the FBI, State, and Navy-would never have been created. However, the facts may well fit into other scenarios, such as the "renegade faction" hypothesis. Oswald appearsfrom the perspective of a potential conspirator with access-to have been a tempting target for involvement because of the sensitivity of his files. It is prudent to remember when speculating about where the argument goes from here that the government and the Review Board have yet to deliver what the Records Act promised: full disclosure.

On the other hand, we can finally say with some authority that the CIA was spawning a web of deception about Oswald weeks before the president's murder, a fact that may have directly contributed to the outcome in Dallas. Is it possible that when Oswald turned up with a rifle on the president's motorcade route, the CIA found itself living in an unthinkable nightmare of its own making?

What Price Secrecy?

It is a shame that protecting sources and methods may have contributed to the president's murder. Each day these secrets are kept from the public only does more harm. Cover stories, deceptions, and penetrations are the kinds of secrets the CIA and FBI will fight hardest to protect. Yet they are clearly the kinds of secrets whose release would signal that the promise of full disclosure has been kept.

We are reading documents that were inappropriately denied to the House of Representative investigation in 1978. Congress created the CIA, and congressional oversight is not possible without access. It is especially wrong for the CIA to withhold information when it is being investigated by Congress.

The issues raised by the past conduct of our intelligence organizations must be discussed openly. Practical, effective solutions must be found. Tangible measures must be devised and implemented that will build reasonable constraints into the system and the public's confidence with them. For example, no federal agency should ever be allowed to obstruct the course of justice in order to protect a source. This issue should not be politicized. It does not belong to the right or the left. It is one of the fundamental ethical issues of the late twentieth century. Do we have any practical means of enforcing compliance with this principle? In fact we do, and it need not cost the taxpayer a penny. We need only to add one question to the polygraph exam.*

If we can rationalize using these devices in order to protect intelligence, we can use them to protect the interests of the people.

The story in these pages is a story about how a redefector from the Soviet Union became increasingly embroiled with targets of the CIA and FBI, about how he was used in New Orleans and in Mexico City, and about how, after the Kennedy assassination, history was altered to obscure these links with the president's accused murderer. It raises fundamental constitutional issues. What legal term should we use to describe the action of a government agency when it lies to a presidentially appointed investigation? Obstruction of justice? Can institutions be held accountable if the people who work for them lie to a formal congressional investigation? Is this "perjury" or "misleading Congress"? These may sound like questions for lawyers, but they are also issues for citizens. What do we do when we discover lies by a government agency thirty or forty years after the act?

The secrecy in which intelligence agencies conduct their operations has the unfavorable effect of insulating abuses from detection. So much time elapses before the facts are declassified that there is little interest left in reforming the aspects of the system that led to the abuse. As early as 1976 Henry Commager observed:

The fact is that the primary function of governmental secrecy in our time has not been to protect the nation against external enemies, but to deny the American people information essential to the functioning of democracy, to the Congress information essential to the functioning of the legislative branch, and-at timesto the president himself information which he should have to conduct his office.'

A different criterion for secrecy-from the perspective of the people's need to function effectively at the ballot box-is needed. That might suggest, for example, that the basic period of classification be reduced to four or eight years, to coincide with the presidential rhythm of the national security apparatus.

Many of the political and social issues that have emerged from the history of the Kennedy assassination as a conspiracy "case" will find their resolution in years to come, when less will be at stake and American academe can discuss them safely. In the short term, there are compelling realities that must be faced. The moment the JFK Records Act was passed, we passed the point of no return. Not releasing the government's files now does more harm than good.

As diverse a people are we Americans are, we are unified by the democratic concepts we share: that ultimate power belongs with the people, and that the government cannot govern without the consent of the governed. For thirty years we have watched aghast as one lie begot another and as one half-baked solution gave way to the next, and our confidence in our institutions slowly dissipated. At the heart of this situation is a relatively new development in American history: the emergence of enormously powerful national intelli gence agencies. As Commager so eloquently observed twenty years ago:

The emergence of intelligence over the past quarter-century as an almost independent branch of the executive, largely immune from either political limitations or legal controls, poses constitutional questions graver than any since the Civil War and Reconstruction. The challenges of that era threatened the integrity and survival of the Union; the challenges of the present crisis threaten the integrity of the Constitution."

The unsavory truth confronting American citizens, just as it confronts the citizens of Russia and China, is this: Unbridled power cannot reform itself. The reform of the intelligence system is something the people, not the intelligence agencies, must control.

Because the Kennedy assassination is but one instance of hiding the truth, the passage of the JFK Records Act and how honestly it works have implications for the government's records in all cases where its acts are questionable in the eyes of the people. The stakes are high, and include nothing less than the credibility of our institutions today. The present generation has the responsibility to hold the government accountable.

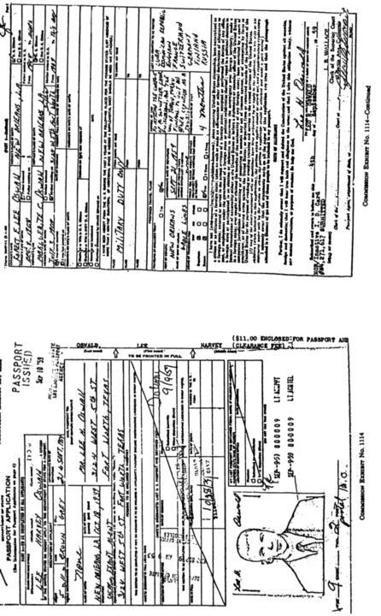

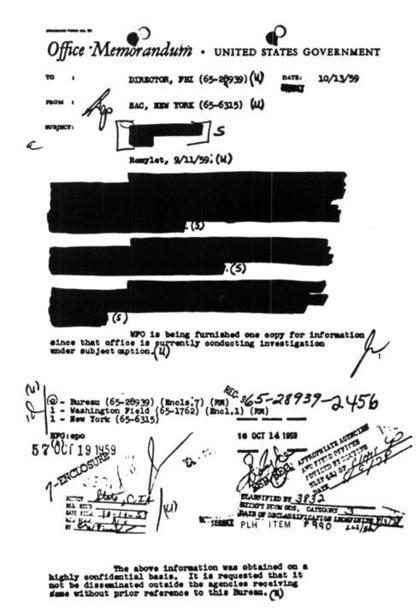

Documents

This work is based primarily on documents released since 1992. Some of the documents referred to in the approximately 1,500 footnotes have been included here for convenience. Most are new. Those that are not new are less redacted versions of what was previously in the public record. All are available in the National Archives.

The documents published in this annex are generally arranged in chronological order. Some, however, have been grouped according to a particular subject. There are five such subject categories: American defectors, HT/LINGUAL materials, Fair Play for Cuba Committee handbills and associated literature, CIA Routing and Record sheets, and documents associated with Oswald's September-October 1963 trip to Mexico City.

For more information on documents, photographs, and documentary working aids, write to John Newman, P.O. Box 592, Odenton, Maryland, 21113.