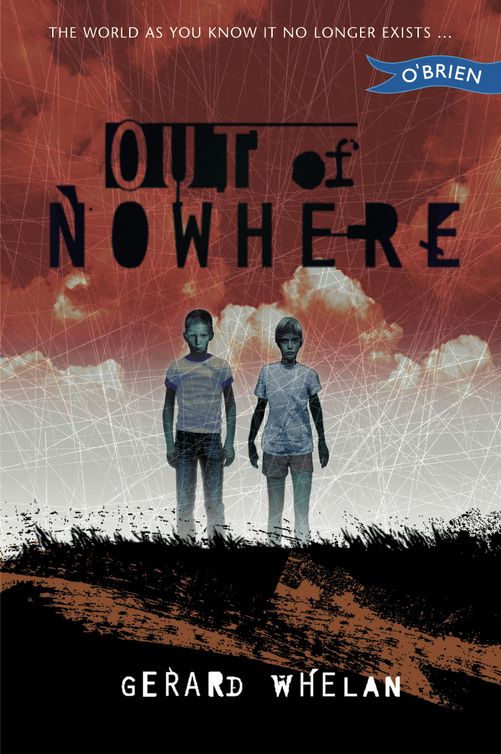

Out of Nowhere

Authors: Gerard Whelan

OUT OF NOWHERE

Nominated for the Bisto Book of the Year Award 2000

‘An excellent book … I found myself intrigued by and drawn into the fascinating world that Whelan weaves around his characters. The frenetic pace keeps us constantly turning the pages.’

Sunday Business Post

‘The sort of story to make your hair stand on end. It keeps its biggest surprise to the end – as all good thrillers do!’

Southside People

‘This is an absorbing action-adventure story, but it’s also a study of what it is to be human and how difficult it is to disentangle oneself from violence. It’s far more imaginative and better written than most and its essential seriousness is undercut with humour. A damned good read, no matter what age you are.’

Siobhán Parkinson, IT magazine

‘It makes the

X-Files

look cosy.’

RTE Guide

‘In this taut thriller, Whelan has created an imaginatively eerie new world.’

Irish Times

‘Not for the faint hearted! This thriller, with its twists and turns is certainly one that kids will love to fear!’

Parent & Teacher magazine

‘Prepare to accept the fact that the world as you know it no longer exists …’

Irish Independent

Dedicated with respect, admiration

& above all affection

To one of England’s more durable exports,

The one and only Ms Carolyn Swift

Ta very much to the original readers:

Eoin Colfer, Liz Morris, Frank Murphy,

Larry O’Loughlin and Claire Ranson.

Final work on this book was done in New York. It wouldn’t have been possible without David Smith of Manhattan, who gave me access to his computer, e-mail and phone.

First there was nothing at all. Then a blurred glimpse of robed figures standing over him and a cold feeling of fear. And then again nothing, neither threat nor rest nor dream.

When Stephen came to he was lying on a hard bed. He opened his eyes and found himself looking up at a low ceiling made of plain dark wood. It wasn’t a ceiling he recognised, he was certain of that.

He raised his head and looked around. The room he was in looked like a film-set. The walls were of bare stone. Dark curtains were pulled across the window. Such light as leaked through was dim and, beyond the fact that it was daylight, he couldn’t guess the time.

Apart from the bed that he lay on, there wasn’t much furniture in the room: a large square table, two wooden chairs, a huge cupboard and a small bedside locker. On the table was a large three-branched candlestick with three fat unlit candles standing in it. A large rectangular mirror hung on the wall by the window. The heavy wooden door, the only exit he could see, was closed.

Stephen raised himself on one elbow and looked around slowly. He was sure he’d never seen this place before. It was then, as he tried to remember where he might have expected

to wake up, that he became afraid. Because he couldn’t remember. He couldn’t recall going to bed, and he couldn’t recall who he was. Apart from the fact that his name was Stephen, he couldn’t remember anything about himself at all.

He lay still, thinking hard. He tried to remember a single other fact about himself, and failed. He was a mystery to himself. Had he been in some kind of accident? But this didn’t look like a hospital room. It hardly looked like a room from this century at all.

He was distracted by the sound of a man’s voice shouting. The voice shouted again and again. It sounded both pained and angry, but the words were in a language Stephen didn’t recognise. There were other voices too now – lower, calmer, soothing. The man stopped shouting, then the other voices stopped too.

Stephen got out of bed, curious, and moved towards the window – the shouting had come from right outside. He saw that he was dressed only in underwear, and looked around for something else to cover himself with. There was a dark robe draped across the foot of the bed. He put it on. As he tied the cord around his waist, the door opened a little. A head peered in. The boy couldn’t see the face in the dim light, just a silhouette.

‘Ah,’ said a thin, accented voice. ‘You are awake, young man.’

‘Yes,’ Stephen said, not knowing what else to say.

The head nodded. ‘Good. I’ll tell the abbot.’

The head withdrew, and the door closed. The boy stood staring at it. The abbot? Was this place an abbey? Then,

remembering what he’d meant to do, he crossed to the window and pulled back the curtain. Bright light burst in, almost frightening him. He was looking down from an upstairs window. Opposite the window he saw cloisters, a stone wall pierced by arched windows, and an open doorway with shadow beyond. Below him lay a courtyard filled with light. In the middle of the area he could see stood an old-fashioned covered well. There were no people in sight.

From the corner of his eye Stephen caught a glimpse of movement within the room. He turned quickly and faced himself in the mirror. He stared at a stranger. Dark hair, pale face, a slight form. Worried eyes. Thirteen years old? Fourteen? He had no idea.

He was afraid.

There was a knock at the door and two men came in. Both wore long dark robes. One was talking as they came in, and Stephen recognised the voice of his recent visitor. He was a thin, slight, balding old man with a shrewd face that looked lived-in. But it was his companion who held Stephen’s attention.

This man seemed to glide into the room. He was very tall and very thin. His hair, partly covered by a skullcap, was salt-and-pepper grey and cropped tight. His head was large, his face long and angular. His lips were thin. He had deep-set, watchful brown eyes; at the moment they were watching Stephen, frankly, carefully.

The man glided to the table and stood there without speaking. The other man stopped walking too, but kept talking.

‘… we’re doing our best,’ he was saying, ‘but there simply aren’t enough of us. We can’t watch all of them all of the time. Philip only turned his back for a moment. He’s very annoyed with himself.’

The tall man raised one hand. The shorter man stopped speaking abruptly, as if he’d been switched off. The tall man – monk, rather, for they were obviously monks – didn’t take his eyes off Stephen as he spoke to his companion. His English was perfect, but to Stephen his accent sounded foreign.

‘Philip is always annoyed with himself,’ he said quietly. ‘Tell him to calm down. He won’t listen, but tell him anyway.’

The small monk nodded and left. The other stood looking at Stephen. Stephen remembered what the first monk had said when he found him awake. This, then, must be the abbot. Stephen had a hundred questions he wanted to ask, but he didn’t know where to begin. The abbot’s brown eyes seemed to bore into his, to look right past them and inside his head.

At last the abbot spoke.

‘You’re sane,’ he said. It wasn’t a question. He sounded relieved.

The boy stared at him.

‘Am I?’ he asked.

The abbot looked concerned.

‘Are you in pain?’

‘No. But I’m scared. What happened to me?’

The monk made a fluid gesture with his long hand, indicating a chair.

‘Please,’ he said, ‘sit down.’

Stephen realised that his knees were trembling. He felt weak. He sat. The abbot sat opposite him.

‘I’ll tell you what I can,’ the monk said. ‘But first I must ask you one question: can you remember anything at all about what happened to you?’

‘No. I was hoping you could tell me. My name is Stephen, I know that. But I don’t know a single other thing about myself. I don’t know who I am.’

He heard a ghost of panic in his final sentence. But the abbot breathed what sounded like a sigh of relief.

‘Thank heaven,’ he said.

Stephen couldn’t believe his ears. His fear and frustration turned to anger.

‘I’ve lost my memory,’ he said, ‘and all you can say is “Thank heaven”?’

‘I beg your pardon,’ the monk said. ‘I forget my manners. It’s just that I’m so used to talking about this now. We speak of little else. And so few of our guests are as lucky as you.’

His words made no sense to Stephen. ‘What happened to me?’ he demanded.

‘I don’t know,’ the abbot replied.

‘But you still call me lucky?’

The monk rested his chin in one hand. He pursed his lips and cast his brown eyes downwards. Without their penetrating gaze, his face looked different. It was still strong, but you could see a strained tiredness there too.

‘I’m trying to put myself in your position,’ he said slowly. ‘So as to know how best to explain it to you. We know so little ourselves, really.’

Stephen wanted to scream at him to stop dawdling. But then the brown eyes flicked upwards again and held his in a steady gaze. They weren’t the kind of eyes you screamed at.

‘You’re not the only person we’re caring for,’ the monk said. ‘There are five others – so far. The first strayed in on Sunday night. A poor lone unfortunate, we thought, a dazed accident victim, perhaps – though there’s very little traffic hereabouts, even in the tourist season. He arrived in the middle of the night. We were all long asleep, but he made so much noise he woke us. It was too late that night to do anything about it, so we sedated him and put him to bed, meaning to contact the police on Monday morning to explain the situation. Well, he was certainly a poor unfortunate: but he wasn’t alone. We found you wandering near the abbey on Tuesday, also dazed and disoriented. You were the third person we found. Today is Thursday, and we have six.’

Stephen was stunned.

‘In four days?’ he asked. ‘You’ve found six people with amnesia in four days?’

‘I wish we had. Including yourself, we’ve found only two amnesiacs.’

‘And the others?’

‘Ah,’ said the abbot. ‘The others.’ He was silent.

‘You still haven’t contacted the police?’ Stephen burst out. ‘Or a hospital?’

‘That’s the problem, do you see,’ the abbot said. ‘There don’t seem to be any police or hospitals.’

‘What?’ Stephen gasped.

‘Something …’ the monk began, hesitantly, ‘… something

has happened.’

‘What do you mean?’

The monk sighed again. ‘I don’t know,’ he said. ‘That’s the simple truth. But I suspect it must be something very terrible. Apart from those of you who’ve wandered in, we can’t contact anyone. We can’t even find anyone. Any houses we’ve searched are empty. So is the closest village. We can’t contact anyone on the telephone. All the animals are still there – but not a single human being.’

Stephen couldn’t take this in. It sounded foolish. ‘Radio?’ he said. ‘Television?’

The abbot shook his head. ‘We have both,’ he said. ‘On Sunday night everything was as usual, but since Monday morning there’s been nothing on any channel, local, national or foreign. And even to try them we have to use our own small generator because there’s no electricity either.’

Stephen was stunned. An awful thought came to him. He had a terrible vision of mushroom clouds.

‘A war?’ he croaked.

But the abbot shook his head. ‘We’d have seen something,’ he said. ‘And so far as I know, there are no weapons which can destroy humans and leave animals alive. Not yet, anyway, though I’m sure someone’s working on it. No. All we know is that on Sunday everything was normal, but by Monday morning everything had changed. Something – whatever it was – happened during the night.’

A sudden thought struck the boy. ‘What about the other four people who don’t have amnesia? Don’t they remember anything?’

The monk sighed again. It was a lonely sound. ‘Oh, yes,’ he said, with immense sadness. ‘They remember things all right. Two of them remember the end of the world. One even remembers creating it. They remember monsters and spaceships and vampires. One recalls living in fairyland. Another one says nothing at all – except sometimes he howls.’

He shook his head sadly. ‘The reason I was pleased that you’d lost your memory,’ he said, ‘can be explained by the very first words I said to you when I came in. Do you remember what they were?’

Stephen didn’t have to think. ‘Yes. You said: “You’re sane”.’

‘Indeed. You’re sane. So is our other amnesia victim. But those of our guests who seem to have memories, they, alas, are not sane. None of them. They are all hopelessly mad.’