Outposts (42 page)

To the west, shining gold in the afternoon sun, lay San Carlos Water, and Falkland Sound. Three months ago there would have been nothing there but the water and the birds—perhaps the little island packet, or a yacht, or a child in a rowing boat off for a day’s fishing. This afternoon six warships steamed at anchor, their guns ranged high, their radars swinging round and round on perpetual

watch. But no Admiral Sturdee here, with battleships and cruisers bent on some mighty task; these were mere sentry ships, stationed to ensure that for the time being there was some truth in the old Imperial axiom about Holding what we Have.

‘Come on—no time for gazing!’ shouted the man from the Ministry of Defence. The helicopter rotors were up and running, and it was time to whirl away and leave the islanders to their own devices. Their lives had been shattered, and changed for ever—and all for the preservation of a sad corner of Empire which, by rights and logic and all the arguments of history should, by some device or other, be permitted and encouraged to fade away. Arguments were later to be advanced about the need for keeping the Cape Horn passage in safe hands, for the day when Panama fell to the other side. But most of the world, perhaps less sophisticated and more cynical than it should be, saw this as quite simply the pointless preservation of Imperial pride. And yet the preservation could only last a few more years, or a few more decades; when finally it was allowed to die, how senseless this tragedy would all appear, how wasted all the lives.

And then I was aboard the plane again, and the islands were falling away below, and had become a small green patch in the great grey ocean, with a British flag still flying, the guardian of the useless.

Pitcairn and other Territories

Pitcairn and other Territories

After three long years, and tens of thousands of miles, the Progress was almost over.

At the very start, when I first hauled out all the almanacs and atlases and diplomatic lists and gazetteers I counted rather more than 200 islands of any significant size that still belonged to the Crown—and thousands more, if you bothered to count every last skerry and reef where England’s writ still ran and England’s sovereign ruled. But I had done what I had wanted to do: I had managed to get myself to every colony that still had a British Imperial representative, and still had a population—everywhere, in other words, that was likely still to have the feel of Empire to it.

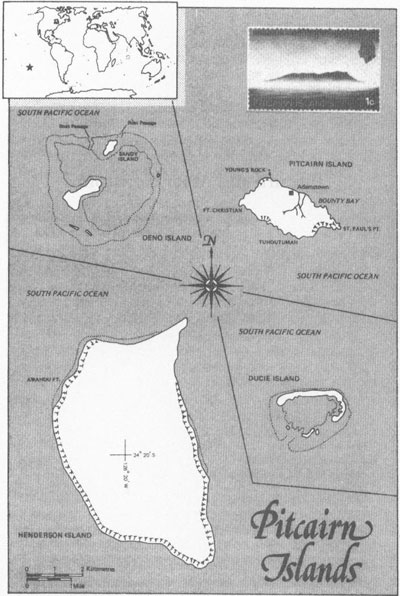

But I had had to make some hard decisions. One of the most difficult concerned whether or not I should go to Britain’s sole remaining possession in the Pacific Ocean, the group of four tiny and barely inhabited rocks made notorious two centuries ago as the refuge of the

Bounty

mutineers—the Pitcairn Islands.

Three of the four islands of the colony have no population at all; the fourth, Pitcairn itself, has but forty-four islanders, and the number is declining slowly but steadily. There is no resident representative of the British Crown. (The Governor is also the British High Commissioner in Wellington, and he tries to make a brief visit every two years. The Island Administrator doesn’t live on Pitcairn either, but in Auckland, 3,000 miles west.)

There is precious little communication between the Pitcairners and the motherland. Adamstown, the tiny capital named after one of the mutineers (and peopled by more than a dozen islanders whose surname is Christian, and can trace their roots back to Fletcher, the architect of the whole affair), does not rank high on Whitehall’s

diplomatic priorities. Hardly any British money is spent on the place: if the Pitcairners need anything urgently they have to talk to Auckland by morse code, though they have been helped in recent years by a market gardener near London, who listens out for the islanders on his ham radio set. If they want anything particular he will buy it out of his own pocket and see that it is loaded on to the twice yearly supply ships. There is no island doctor; when Betty Christian fell victim to a particularly pressing gynaecological problem the island pastor (a Seventh Day Adventist, to which church all the islanders belong) had to operate. He had never carried out surgery in his life before, and the instrument needed for the operation was not in stock among the rusty scalpels and plasters in the Adamstown dispensary. So they hand-forged the necessary item, and the pastor was led through the operation, step by step, by a surgeon speaking by radio from California, 8,000 miles away. At moments like this Pitcairners have good reason to think they and their tiny island are being shunned by the policy-makers and the bureaucrats in London.

The two supply ships usually call at Pitcairn while on their way somewhere else. Most of their skippers are reluctant to stop at all, and when they heave to off the lonely cliffs to take off stores they are invariably impatient to get under way again. A visitor who chooses this means of arriving is lucky if he gets ten hours on the island unless, by accident or design, he misses the boat, in which case he stays for the next six months. When I came to plan the journey the ten-hour option seemed worthless, the six months excessive. I decided, with some sadness, that I would not go at all.

I went instead to the village of Frog Level, Virginia. The connection between the tiny Pacific Crown colony and a rundown community in the Appalachian Mountains—not one that is immediately obvious, it has to be admitted—was provided by one of the local residents. He was named Smiley Ratliffe, and he lived in an extraordinarily vulgar mansion with fences, guntowers and a collection of five Rolls-Royces, each equipped with spittoons to accommodate his soggy plugs of Work Horse tobacco.

Mr Ratliffe, who knew nothing of the mutiny story and confessed to not having read a book since he was a GI in 1945, was a lonely

and unhappy millionaire. He had made his fortune from running coal mines in the hills of Virginia and Tennessee and Kentucky, and he had developed a profound, almost pathological loathing for the insidious evils of Communism, Freudian analysis, big government, narcotics and Elvis Presley. For most of the 1970s he had spent his days flying and cruising around the world in search of a deserted and idyllic island where he could be guaranteed total freedom from all taint of the Red Menace, and all the other evils that disturbed his tranquil routines. In 1981, towards the end of another long and fruitless quest, when he was heading sadly homewards from Tahiti, he stopped by to see the good folks of Adamstown, liked them mightily and proceeded, as he tells the tale, to one of the three other islands that make up the Pitcairn group.

It was called Henderson Island, was four miles long, two miles wide, was surrounded by vertical cliffs forty feet high and was almost perfectly flat. Most mariners would not give the place a second thought. Pitcairners occasionally stopped by to pick up wood to carve, but thought little of their neighbour. Like Ducie and Oeno, the others of the forgotten Imperial quartet, Henderson was just another coral island, with nothing to commend it, and no particular quality aside from its isolation. A man had been put ashore there with a chimpanzee some years before, but had gone mad inside three weeks, and had to be taken off by a passing ship.

But Smiley Ratliffe very much liked what he saw. He had no doubts from the moment he first spotted her, that this was to be his island home. He had a sudden dream, a veritable vision. He saw his now-beloved Henderson Island nurtured and brought to civilisation by the best efforts of the fine folk of Frog Level. He saw an airstrip, a mansion, lovely ladies dancing under the Pacific stars, endless supplies of Work Horse tobacco, no taxes, no psychologists and, best of all, no Communists. And so, fired with evangelic fervour as befits a man who has discovered paradise, Smiley Ratliffe returned home to America, and with all the uncomplicated enthusiasm that is peculiar to the rural American millionaire sat down and wrote a letter: he wanted to buy Henderson Island, price (more or less) no object.

The Foreign Office gave a polite cough, and said that, no, actually, Crown colonies were not actually for sale, and certainly not to aliens. But Smiley was not that easily put off. He had heard the Pitcairn Islanders grumble about how London spent so very little on them—so he played a shrewd hand. He told the Foreign Office he would give the Pitcairners a million dollars if he could just lease Henderson—999 years should do the trick, he said—and, moreover, he would throw in a ferry boat and would build an airstrip on Henderson so that the group of islands could have certain access to the world outside.

And this time—for such are the ways of today’s Imperialist mind—the Foreign Office stopped short, and began to think very seriously about Mr Ratliffe and his money. Every Empire builder, it seems, has his price.

For a while—and particularly during those rainy summer days when I would go and see him at his desk in Frog Level—old Smiley was able to dream. He drew up the most elaborate plans—men would be shipped into Henderson by landing craft, and would have the airfield built in six months; then there would be dairy herds and a piggery and Smiley’s gun collection and his thousands of cowboy videotapes, and his new mansion built and his girlfriends brought over…two years, maybe, and paradise would be ready for him. Lord Belstead, the Foreign Office man who was considering the case, had told Parliament itself, no less, that the Government was seriously considering the matter. Optimism reigned at Frog Level, and Smiley would drive his Silver Wraiths down the country lanes at a furious pace, scattering the chickens, singing southern songs and giving a war-whoop of victory as he sensed the imminent realisation of his life-long ambition.

But it was not to be. The World Wildlife Fund reminded the world that Henderson Island was a repository for great natural treasure. It wrote a report for the Foreign Office. ‘The Island remains largely in its virginal state. It supports ten endemic taxa of flowering plants, four endemic land-birds (including the Henderson Rail, known to ornithologists as the Black Guardian of the Island), various endemic invertebrates, a colony of fifteen species of breeding

seabirds and extensive and virtually unexplored fringing coral reefs.’ There was a special breed of snail, a fruit-eating pigeon and a parrot that sipped nectar. Mr Ratliffe chewed tobacco, and could not under any circumstances be allowed to settle on Henderson, the Fund declared. Moreover, the island should be protected from settlement by any member of the human species, and left entirely for the world of animals and birds. Her Majesty’s Government, the Fund concluded, ‘has a profound moral obligation to take immediate steps to protect Henderson Island…’

Mr Ratliffe received his letter a few days later. So sorry to have indicated there might be cause for optimism, really cannot permit settlement, unique natural heritage, taxa here, taxa there, nice of you to offer such generous terms, great pain to have to decline kindness, no need to enter into correspondence on the matter, infinite regret, yours respectfully. And down in Frog Level that night there was much chewing and hawking, and sounds of disgust rattled around the Appalachian hills as Smiley Ratliffe unburdened himself of yet more invective, and prepared to begin his search once again, for a place where there were no drugs, no psychiatrists, no rock stars, no Commies and, particularly, no officials of the British Foreign Office. They, in Mr Ratliffe’s view, were the worst of the lot of them. ‘Hell, they were gonna sell me the goddam lease. They didn’t give one tuppenny damn for the place. They jes’ saw it as a way of making a million bucks—until them critturs weighed in on the side of some pesky little ol’ snail, and some dingbat of a parrot, and the British realised they wouldn’t look so good to a bunch of parrot-lovers. Damn hypocrites, you British! Just damn hypocrites.’ And I left Frog Level forthwith, and have not spoken to Mr Ratliffe since.

On Pitcairn Island the news was received with sullen dismay. The islanders wanted the money, and the ferry, and thought an airfield on Henderson would be a good idea. Mrs Christian could have had a doctor flown in from Tahiti, they said. When we have a problem here someone could fly in, they said. Who cares about fruit-eating pigeons, and birds called Rails, they said.

The Foreign Office said it was moderately sympathetic. Glynn

Christian, a young man related to most of the island families, and who now lives in London demonstrating cooking for early morning BBC television viewers, planned to lead an expedition to go to Pitcairn in 1989 and study the animals and birds. It would leave behind its boats and its buildings for the bicentenary the following year of Fletcher Christian’s arrival; a royal visit would take place then as well, he hoped. Pitcairn would be put back on the map.

His idea was, essentially, to rescue the colony from extinction. He, and those few friends of Pitcairn to be found in Britain, are convinced the Foreign Office wishes the island to be depopulated totally—the last few islanders should go to New Zealand, or to Norfolk Island, and live a better life. If the trend of the last two decades continues, no one will be left on Pitcairn by the end of this century, and the rocky islands of this tiny and remote group will be left to the wind and the waves, the pigeons, the parrots and the snails.

But lately one additional argument is finding official favour: it concerns the strategic importance of the Pacific Ocean. The argument is simple. The sovereign sea area that surrounds the four islands of Pitcairn is vast. There are said to be dark forces—the very forces Mr Ratliffe so despises—who would dearly like to fill any Imperial vacuum that might be created in what President Reagan called ‘the Ocean of the twenty-first century’. The depopulation of Pitcairn might create such a vacuum: the argument for trying to retain at least token inhabitation, a small band of colonists set down in the silver sea, is more powerful than can be influenced by mere considerations about ecology, or sentiment, or the bicentenary of an event that official Britain would prefer, in any case, to forget.

The decision not to visit Pitcairn was difficult. I felt no particular regret, however, at keeping away from both South Georgia and the British Antarctic Territory: neither has a population, neither has a resident administrator (though the chief official of the Antarctic Survey acts as magistrate and British Government representative should any problems arise—such as the illegal landing of the Argentine scrap men at Leith harbour in March 1982). The scenery,

of course, appears to be stunning; but such architecture as the Empire has left is the gimcrack wreckage of scientific stations and whaling factories, and only the memorial cross to Shackleton on a snowy hillside above Grytviken appears to have a trace of the Imperial feel about it.

When I began the journey, and mentioned to friends that I was wandering around the world looking at the remaining British colonies, most would look puzzled. ‘Do we have any left, then?’ they would ask. Not a few, though, would assume a more sophisticated attitude. ‘Places like the Isle of Man, the Channel Islands, that sort of thing?’ And in the early days I grimaced inwardly, and gritted my teeth, and said that no, these were not colonies, not part of the Empire, not abroad, you see…

Technically, though, they were right to suggest these most British of Isles for inclusion. (And it is perfectly correct to call the Channel Islands British Isles. The word ‘Britain’ refers to two places—that wedge-shaped island comprising England, Wales and Scotland on the one hand; that duck’s-bill of a peninsula known as Brittany on the other. The latter was always known as ‘Little’ Britain, the former ‘Great’ Britain. The Channel Islands, belonging to both, may have the sound of Gaul about them, but are British through and through.)

Both they, and the Isle of Man, are true dependencies of the Crown. They are not a part of the United Kingdom. They have their own laws, parliaments, taxes and customs. They have a British governor, the representative of the sovereign to whom they own their allegiance and their loyalty. They are willing colonies, their citizenry colonials, in every sense the same as those in Bermuda, on Grand Turk, or up on the Peak in old Hong Kong.