Outposts (37 page)

But the liberality of the Cayman laws has led, it is thought, to some abuse. The islands are generally thought of as the prime resting-place for some of the world’s hottest money—drug money, Mafia money, pornography money. It is rarely provable—the island laws make it a crime even to inquire about a certain bank account. But the island authorities seem to think it is happening, and have looked, without success, at ways of helping the very worried American police agencies who come to trace notorious criminals here, only to find the trail suddenly running cold, as though the fox had dived into the river, and had swum away to safety.

I stayed with an elderly couple in a grand house outside George Town; they were British and had come to retire on Cayman because of the sunshine, and the absolute certainty they felt that, of all places in the world, this would not become tainted by Socialism. They showed me their bank statement one day—a Barclays’ International statement, sent from the branch in George Town. It was of only minor interest until, quite by surprise, another statement fell from behind it. The Barclays’ computer had folded the statement for the next customer—next in alphabetical order, that is—into the same envelope. The customer was a small firm that hired cranes in a town in Yorkshire; it had more than four hundred and fifty thousand pounds on deposit, and I couldn’t help but wonder why. I thought I might telephone when I got home, and pretend I was a detective, and ask why they felt it necessary to keep so much cash in a Caribbean tax haven. But charity, and prudence, prevailed, and I left them alone.

The nervousness of the banking community showed itself after the Falklands War, and the Cayman Islands were briefly worried. There was talk, easily audible in New York and Miami and Houston,

that the British might well want to dispose of their remaining colonies, to make sure no such costly embarrassment happened again. It was all rumour, of course—the reworking of a few editorials in the more radical quarters of the British press. But it set the bankers wondering—were the Cayman Islands secure? Should the money go to Switzerland once more, or to Liechtenstein, or Andorra?

The Governor of the islands, an astute Englishman named Peter Lloyd, a man with a long record of Imperial service—Fiji, Hong Kong, Bermuda, Kenya—recognised the danger signs. A royal visit should do the trick, it was agreed; and so the Queen, on her way to Mexico and the American West Coast, was briefly diverted to Grand Cayman in February 1983. It was expensive—two hundred dollars a minute, someone calculated. Her Majesty was given a Rolls-Royce that had once belonged to Mr Dubcek of Czechoslovakia; she unveiled a plaque for a new road, she saw an exhibition of local crafts (which, it must be said, are limited, and tend to involve turtle shells, conches, and raffia work), she made one seven-minute speech, spoke to some elderly islanders, performed one walkabout and lunched and dined with the island grandees. Government House was not reckoned either grand or secure enough for the Monarch; instead she slept at the headquarters of a company called Transnational Risk Management Limited, which everyone agreed had more the ring of today’s Cayman Islands about it, anyway.

Brief and costly though the tour had been, it underlined Britain’s determination to keep the colony British, come what may. The bankers expressed their relief and their gratitude, and growth resumed, as though the Falklands War had never happened. The islanders had already expressed their own thanks—a fund-raising campaign under the title ‘Mother needs your help’ was organised by the Caymanians to help the bereaved and the injured from the South Atlantic, and the Caymanians contributed to the tune of twenty-eight pounds each, indicative both of their generosity, and their wealth.

However, the Caymans are not particularly endearing islands. There is no scenery (except underwater, where the diving is said to be

among the best in the world); there is a relentless quality to the money-making on which the islands seem so firmly based—seminars on tax-avoidance in every hotel, beach lectures on insurance, advertisements for Swiss banks and tax-shelters and financial advice centres. There is little left which is obviously West Indian about the place: it seems like an outpost of Florida, rather than of the British Empire, with a tawdriness, a mixture of the seedy and the greedy that was less attractive than the shabbiness or the decay of the other islands.

But that is a churlish judgement. The lives of the Caymanians are undoubtedly much more comfortable than those of their brother-islanders up in Tortola, or across in Montserrat. Why should I deny them a life that gives them such riches? What was it that bothered me about the place?

Perhaps, I thought to myself in the airport taxi, it was because one associates British Imperial relics, and associates them rather fondly, with sadness and decay, with the sagging verandah and the peeling paint, the wandering donkeys and the lolling drunks, and with a generally amiable sense of indolence and carelessness. It was not very laudable, maybe—but it was rather, well, pleasant, and cosy. Perhaps because of all of that, the discovery of a colony with 200 telexes and a telephone for every couple and seminars on investment opportunity, and moreover to discover it in a place like the West Indies where efficiency and technology and wealth have never been at a premium—perhaps it was all too much of a shock to the system. I was not, I must admit, at all sorry to leave. The plane took me to Miami, and it was full of men in business suits, and they seemed to be carrying small computer terminals, and read the

Wall Street Journal

. This, surely, had not been an outpost of our Empire? Where was the charm? Where was the Britishness of it all? They hadn’t even seemed terribly keen on cricket.

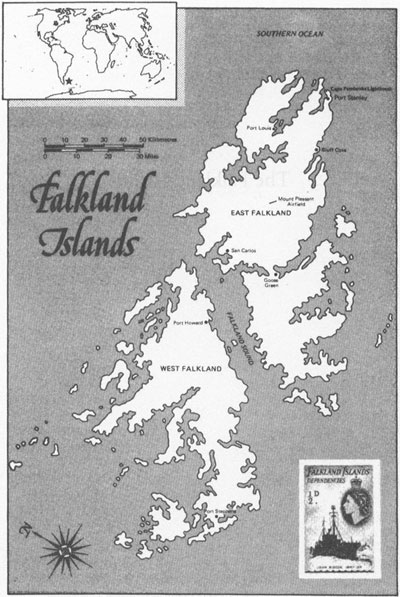

The Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands

It was the first Friday in April—early spring in England, but a crisp clear autumn morning in Port Stanley, the capital of the Crown colony of the Falkland Islands. I was lying wedged under a bed, the Colonial Governor’s chauffeur had one of his feet in my left ear, a terrified cat was cowering under a pile of pink candlewick, and the sound of gunfire was everywhere. Britain’s very last Imperial war—although I didn’t know it at the time—was beginning, and I seemed to be in the very middle of it.

I had arrived three days earlier. This was the first colony I had visited for years, and I had fallen hopelessly in love with the place. Everything, so far as I was concerned, was exactly right. It was a place of islands, and I loved islands. It was cold, and I loved cold places. A fresh, damp wind blew constantly from the west. There was the smell of peat in the air. The grey and purple moors and the white-capped sea-lochs looked as though they had been plucked from the remoter regions of Argyllshire, or Ardnamurchan. The men, slow and deliberate of speech, pipe-smoking, church-going, all dressed in old tweed, oilskins and studded boots, made a modest living as seafarers and farmers; they knew about such things as Admiralty charts and weather and horses and birds and wild animals. They had the old and solid virtues of an earlier age—they were of the same stock as the ghillies and postmen and lobster fishers and shepherds of a seaside town in Northern Scotland, contented with their lonely living, wanting for little, happy to have been passed by and forgotten by the world outside.

And yet on this crisp Friday morning the whole unwanted outside world, with all its awfulness and wasted energies, was preparing to descend upon the Falkland Islands and their people. An Imperial

outpost that had languished for two centuries in the comfort of well-deserved obscurity was about to erupt on to every newspaper and every television screen in every country in the world. A week from this day it would be on the front cover, in full colour, of the major American news magazines, would be the subject of a thousand televised discussions, a matter for urgent diplomacy and for the meetings of presidents, prime ministers, generals, admirals and intelligence chiefs in capital cities on every continent. This morning, at the very moment I had decided it would be sensible to lie on this strange bedroom floor, almost no one in the world was even aware of the existence of these islands, or of this tiny windswept capital town.

And even as I mentioned this irony to the friend who sheltered beside me, a tragedy that was to alter the fortunes of the islands and the islanders for all time was under way, and we were hiding from it among the feet, the frightened cat and the rattle of bullets, among the dust balls and yellowing newspapers under a standard British government-issue bed.

I had come to the Falkland Islands from Simla, the old Imperial summer capital of India. Just a few days before I had been strolling through the grand viceregal lodge, up among the roses and the deodars, with the fine white ridge of the Himalayas in the distance. Then I heard the BBC World Service tell about some curious goings-on in the South Atlantic, with scrap metal merchants from Argentina trying to dismantle an old whaling station on the Falklands dependency of South Georgia, and the British Government being mightily exercised about it. I decided to go home. In the bus that took me from the hills to the plains I read what little there was in the Indian papers about the remote turmoil. It seemed that many of the old southern ocean whalers—and, indeed, the owners of the South Georgia whaling factory—were Scotsmen; and having just come from a building in India that had all the appearance of a magnificent Sutherland shooting lodge I was able to expatiate to the Bengali lawyer in the next seat on the theme the Scots as Empire-Builders, which at least matched his sermon on the Patriotism of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose for length and tedium, after which we both fell into exhausted silences.

The Britain I got home to was more amused than interested in what seemed to be happening on South Georgia. I knew a little about the place, because I had once contemplated applying for a job with the British Antarctic Survey, and had seen pictures of the old granite cross, the memorial to Shackleton, who had died there of a heart attack in 1922. The capital, if such it could be called, was Grytviken, and a small party of BAS men worked there, with their leader nominated as magistrate and representative of the Falkland Islands’ Governor. What appeared to have happened on this occasion was that a small party of Argentinians had landed at Leith, twenty miles up the coast, and were busily dismantling the rusting hulk of the whaling station. The problem, so far as the Foreign Office was concerned, was that the scrap dealers had ignored instructions to check their way through British immigration and customs; a Royal Navy patrol vessel had been dispatched to scare them off, the Argentine Navy had in consequence landed marines and sent in two frigates, ostensibly to support their civilian scrapmen, and both governments were angrily sending Notes to one another demanding discipline, respect for sovereignty, and withdrawal of respective threats.

And so, six days after coming home from India, I was aboard another plane, heading south to write about this ridiculous little argument and, as it was to turn out, an unimagined and unimaginable war. It was a Sunday night, we were droning across the Atlantic between Madrid and Buenos Aires, and I was attempting a crash course on Falkland Islands’ history.

Few seemed to have cared very much for the islands. To the first navigators they must have been terrifying: huge rock-bound monsters, looming out of the freezing fog and giant waves, bombarded by furious winds that screamed out of Drake Passage and howled unceasingly from around Cape Horn. The seas are almost always rough, the air is filled with flying spray, visibility is invariably poor, and navigators and steersmen on passing vessels always had too many tasks to perform at once to enjoy their leisure of island-spotting—the consequence being, uniquely in British Imperial history, that we have no real idea who first came across the Falkland

Islands. The surviving records are confusing—was Hawkins’ Maidenland, discovered by Richard Hawkins in 1594, the north shore of East Falkland? Did Magellan’s expedition discover them, or are those insignificant patches on Antonio Ribero’s maps of 1527 and 1529 records of the Spaniards’ having found them at the start of the sixteenth century? The maps certainly give them a variety of names—the Seebalds, the Sansons, the Malouines, the Malvinas; and only when Captain John Strong was blown into the island waters by a mighty westerly gale in January 1690, and landed and killed geese and ducks, did they assume the name by which the British still call them today: Strong named them Falkland’s Land, in honour of the Navy Treasurer, Viscount Falkland (a man whose career did not flourish, and who ended up committed to the Tower); seventy-six years later John McBride, who established the first British settlement, officially named the entire group the Falkland Islands.

The jumbo jet thundered quietly on. From the flight deck we heard a hushed voice mention that we were a few miles south of Tenerife, in the Canaries. Dinner was over and the stewards moved silently through the aircraft, dimming the lights for a Spanish-dubbed version of

The French Lieutenant’s Woman

to be shown to those few passengers still awake. My reading lamp illuminated the pile of papers I had gathered up before I left London, and I read on.

There were innumerable references to the firm Argentine belief that she had sovereign rights to the Falklands (and persisted in calling them Las Islas Malvinas, after the French from St Malo who had established the first formal settlement, in 1764, and who had claimed them in the name of Louis XV). Of course I was in no position to judge the strength of the various claims: but I remember being impressed by the vigour and constancy with which Argentina asserted her title to the islands, and wondering if there was much more than obstinacy in the tone that successive British Governments had adopted towards the idea of any real negotiations over the islands’ future. I was struck too by the suggestion that every Argentine schoolchild from the age of four knew in the minutest detail the history of the Malvinas, and had an unswerving belief in his country’s entitlement to the islands; I cannot recall ever having

heard anything about them at school at all, other than as a name in the stamp album. (The penny black-and-carmine issue of 1938, with the black-necked swan, and the halfpenny black-and-green with the picture of two sets of whale jaws, were my particular favourites; I promised myself I would look them out when I got back home in a week or two.) Like most Britons I neither knew much about the islands, nor cared greatly about their fate, nor who owned title to them.

Few of the early settlers seemed to have liked the islands. ‘A countryside lifeless for want of inhabitants…everywhere a weird and melancholy uniformity’ was the verdict of Antoine de Bougainville, the leader of the settler band from St Malo. Dr Johnson established the colony’s reputation in 1771, noting that it had been ‘thrown aside from human use, stormy in winter, barren in summer, an island which not even the southern savages had dignified with habitation’. ‘I tarry in this miserable desert,’ wrote the first priest of the Spanish community, Father Sebastian Villaneuva, ‘suffering everything for the love of God.’ And again, one of the first Britons to live on East Falkland Island, an army lieutenant, recalled some years later that the colony was ‘the most detestable place I was ever at in all my life’. ‘A remote settlement at the fag end of the world,’ said one Governor in 1886; ‘the hills are rounded, bleak, bare and brownish,’ wrote Prince Albert Victor, who had sailed in aboard HMS

Bacchante

. The hills, he added, ‘were like Newmarket Heath’.

Charles Darwin went to the Falklands aboard the

Beagle

in 1833, the same year that the Union flag was first raised by a visiting naval vessel. He knew that the existing Argentine garrison had been ordered to leave, and was scornfully dismissive of the Admiralty’s action. He delivered a judgement as haunting as it was economical: ‘Here we, dog in manger fashion, seize an island and leave to protect it a Union Jack.’ Ten years later the islands were formally colonised—an Act of Parliament in London, twenty-eight-year-old Mr Richard Moody came south on the brig

Hebe

to be the first Governor, a Colonial Secretary and Colonial Treasurer were appointed and the dismal new possession was inserted into the Colonial Office List, sandwiched between British Honduras and Gambia (although by

the beginning of this century Cyprus and Fiji had become its closest alphabetical neighbours). Port Stanley was chosen as the capital, thirty pensioners were sent down from Chelsea Barracks, and thirty-five Royal Marines and their families followed shortly afterwards. Governor Moody’s first Imperial decision was to curb the colonials’ keen liking for strong drink. Spirits, he declared, ‘produce the most maddening effects and disorderly excesses’, and he slapped a pound a gallon on liquor brought in to the islands from home.

I must have slept fitfully for a while, for it was morning when I next looked out of the windows, and we were coming in to land at Rio. The Brazilian newspapers were full of news about the Malvinas, and there were pictures on the front pages of the warships

Drummond

and

Granville

, the two Argentine destroyers (despite their names) that were even now cruising around the fjords of South Georgia. Both ships had been built in Barrow-in-Furness, and sold to the Argentine Navy—a measure, it was said, of the enduring amity between Britain and Argentina. Back in London politicians and diplomats set great store by this long-established friendship: here, to the extent I could translate the Portuguese headlines, it seemed to count for rather less. There was definitely the smell of trouble.

A day later and I was in deepest Patagonia. This was very different from the steamy warmth of the River Plate. Here it was very much a high latitude autumn. The wind howled down from the Andes, and whipped up the dust in cold, gritty flurries. I was in Comodoro Rivadavia, a town which I had long thought to be blessed with one of the prettiest names in the Americas. I had tried to get there two years before to write about a simmering dispute between Chile and Argentina over the ownership of a group of small islands off the coast of Tierra del Fuego; but the Pope stepped in to moderate, and the dispute collapsed, and there was no reason to go. Now I was here, and the place was a terrible disappointment. It was littered with the accumulated debris of the oil drilling business—rusty iron girders, enormous pulley blocks, barrels, abandoned lorries, stores dumps behind barbed-wire fences. The buildings were modern, and ugly, and the people walked bent over into the cold gales that blew along the alleys. (It was the second time that I had come to

expect too much from a lovely city name: years before I had spun wondrous fantasies about a place called Tucumcari in New Mexico; but when I got there it was just an oily little truckstop on Route Sixty-six, best avoided. I felt much the same way about Comodoro Rivadavia.)

Flying to the Falkland Islands has never been easy. In 1952 a seaplane made a remarkable journey all the way from Southampton to Port Stanley, by way of Madeira, the Cape Verde Islands, Recife and Montevideo. She took seven days, turned round a few days later and flew home. Then in 1971 a lighthouse keeper—the Cape Pembroke Light on East Falkland was one of the few remaining outposts of the Imperial Lighthouse Service—fell ill, an amphibious aircraft of the Argentine Navy flew in to evacuate him, and then agreed to fly to and from Port Stanley twice a month with passengers and mail. A year later the state-run Argentine civil airline took over the task, and ran a weekly service to the islands. It was an excellent arrangement for both sides: the Falkland Islanders had an air service, and the Argentines could keep an eye on the colony. Moreover, with a small office in Port Stanley, manned by a serving naval officer (to which the colonial authorities seemed to express no objection), the Argentine military had a foothold—one that was to prove useful just a few days after I arrived.