Outposts (34 page)

‘Coffins for Sale—No Credit.’ The sign was the first I noticed as

my car bumped its way slowly up from the quayside, and to The Valley. It was, indeed, another shabby island, its capital another shabby town. Not forlorn, though, in the way that Cockburn Town had been forlorn; this looked like a place that had been overlooked for a long while, but was just being discovered, and was on the edge of better times.

‘Bank of Nova Scotia’ was the second sign I saw, and notices for banks and insurance companies turned out to be more numerous than any others. Small armies of workers were sawing and hammering away at rows of shops, twenty shops to a row, two rows to a complex. But on looking more closely the shops turned out to be little banks—some of them very odd banks, and from countries a very long way from Anguilla. But the building of them evidently gave the Anguillians work, and the Chief Minister—the same Ronald Webster who was sitting in his bath when the Red Devils burst in—promised me that many more would be invited over the coming years. (Mr Webster was defeated in an election soon afterwards, but the policy of turning Anguilla into a tax-haven was still being pursued with great energy.)

Hotels, too, were springing up. Anguilla’s coastline—seventy miles of it, almost untouched—had just been discovered by American entrepreneurs (and by a Sicilian, who had been flung out of Saint Martin and who was hoping to salt away his millions in a beach under the protection of the British Crown; he was asked to go elsewhere) and by a growing number of wealthy tourists. I fell in with a curious crowd one afternoon: he was a Greek-American, from Boston, and he said he was one of the leading potato brokers on the East Coast. He would keep me in close touch with happenings in the world of American potatoes for months thereafter, going so far as to send me a laudatory book about the Idaho variety, called

Aristocrat in Burlap

. We sat on a pure white beach, under an umbrella, and spent a good hour watching a pelican as it flew lazily over the endless blue rollers. It was a wonderful, faintly terrifying sight as the bird did its trick. It would be flying along, quite calmly, rising and falling in the thermals. Suddenly without warning, it would crumple up, all bones and wings and disordered brown feathers, just as if it

had been shot. Down, down it fell, into the sea. At first we thought it had died, but after ten seconds or so it would emerge from the sea with a splash and a shower of spray, like a watery Phoenix, and would fly off in happy triumph, with a blue-and-gold fish clamped in its beak. It repeated its act time and time again, and each time the Greek potato king would laugh till the tears came; and we looked further along the beach and other pelicans—Eastern Browns, the book said—were doing the same thing, raining down into the sea and flying off with their flapping harvest of fish. We wondered who was enjoying the more perfect idyll—we two, or the birds.

I had a friend on the island, a man who had been the Attorney-General on St Helena and who had married a Saint of exquisite and serene beauty, and had then decided to leave and look for work on another colonial possession. They had given him the job of ‘A-G’ on Anguilla, and he was having a rare old time—no murders on the island perhaps (the only prisoner in The Valley had been sent there for using bad language) but an exquisite dilemma over a drugs case in which he was deeply involved.

Off the eastern tip of Anguilla lies Scrub Island—a couple of miles long, with two low hills, a tiny lake and a rough grass airfield. The latter had no obvious legitimate use, since no one lives on Scrub Island, and hardly anyone goes there (the

Baedeker

lamely reports Scrub Island as having ‘much fissured coral rocks’ and little else). But the airfield did have an important use for the classic non-legitimate business that has become a mainstay of Caribbean commerce—the trans-shipment of cocaine. A plane would fly out from Florida, empty; another would fly in from Bogota, full; there would be a hurried mid-night transfer, whereupon the two aircraft would return to their respective lairs, and plan to meet again later. Scrub Island, Anguilla, became, in the early 1980s, one of the great unsung drug markets of the Western world.

Until one evening in November 1983. The American drug enforcement agencies got wind of a big transfer plan, and called Anguilla, and spoke to my friend who had just arrived from Jamestown. He alerted the Royal Anguilla Constabulary, advised them to draw guns from the armoury, sailed them out to Scrub

Island and hid them behind the clumps of loblolly pine and seagrape that grew beside the airstrip.

A man arrived in a launch, and set about lighting small fires to mark the strip. Then the aircraft arrived, as expected—one from the west, one from the south. Two men climbed from the Colombian craft, one from the American machine, everyone shook hands, and the policemen could see bags being humped from one hold to another. They drew their service revolvers, switched on their arclights—and made the most spectacular arrest Anguilla had ever seen. Four big-time drug smugglers, and a haul of a quarter of a tonne of cocaine—the largest and most valuable capture ever made in the Caribbean. It was worth one thousand million dollars.

The sheer scale of the haul posed one immediate problem. The Governor, a pleasant and very quiet Scotsman who had been brought to Anguilla from a lowly post in the British Embassy in Venezuela, was deeply alarmed. What, he wondered, if the Mafia tried to get it back? A billion dollars’ worth of drugs would make it worth some gangsters’ while to take almost any steps imaginable. They might land in force, at night, armed with heavy weapons. He might be captured, the Chief Minister might be assassinated, the colony might revert to the suzerainty of some Lower East Side

capo

. It was too horrible to contemplate. He wondered whether to ask for a frigate to stand off the coast, but then decided the evidence would be much safer under the care of the Americans, and had it all shipped off to Florida, and breathed a sigh of great relief when it had gone.

The four prisoners, on the other hand, represented a very considerable windfall. All were released, on half a million dollars’ bail. They were told to come back for trial three months later, and when I met my friend he was praying hard that they would decide to skip bail—he would take great pleasure in leading their prosecution, of course, but he and the colony would very much like the money as forfeit. And in any case—what if they were found guilty? Where could they be kept? What if their Mafia chums tried to free them? And the drugs would have to be brought back as evidence, too.

In the event they never did show up. The Government of

Anguilla made a clear profit of half a million United States dollars, and was able to tell the British Government, which wearily and reluctantly hands out grants to poor islands like Anguilla each year, that on this occasion at least it would need less of a grant than normal. It might even be able to afford a new school, or an extension for the hospital, out of the proceeds. It is, my friend remarked, an ill wind…

In one classically Imperial sense, Anguilla is a colony of some importance. Because of where she is, the colony controls—or, put another way, Britain controls—a vital sea lane. And this has come about because of a clever piece of sleight-of-hand which Whitehall played when St Kitts became independent, and Anguilla refused.

Thirty-five miles north-west of Anguilla is a tiny islet, two miles long, shaped like a Mexican hat, and called Sombrero Rock. It has a large deposit of phosphate, and because of that has been visited by quarrymen from time to time, and a few tonnes have occasionally been shipped away. The true importance of Sombrero is that it lies directly athwart one of the busiest deep channels between the Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, and it has a lighthouse. The Admiralty bible,

Ocean Passages for the World

, lists Sombrero among the world’s great reference points (and gives specific routes from Sombrero to, among others, Bishop Rock, the Cabot Strait, Lisbon, Ponta Delgada and the Strait of Gibraltar).

The light on Sombrero—157 feet high, visible from twenty-two miles, and exhibiting a white flash every five seconds through the night—has always been British. It used to be run by the Imperial Lighthouse Service; it was one of the final three in use when the Service was abolished (the others were Cape Pembroke on East Falkland, and Dondra Head in Ceylon).

But Sombrero belonged to the presidency of St Kitts-Nevis-Anguilla, and, so logic dictated, should have moved to the newly independent St Kitts in 1967, since it had no population, other than a British lighthouse keeper. But—and here was the cunning move—London decided that Sombrero should remain British, and remain attached to Anguilla. For this one reason Britain was well pleased

with the Anguillian rebellion—it enabled her to keep control of a lighthouse, and a sea lane, that would otherwise have fallen under the less predictable rule of a newly independent state.

The Board of Trade took over the light, turned it into an automatic station, and brought the keeper home. And then in 1984 Trinity House, which looks after all British home waters’ lights, as well as Europa Point off the southern tip of Gibraltar, assumed control over Sombrero, too. Thanks to the existence of Anguilla and her minuscule limestone possession to the northwest it was still true, technically, and on a very small scale, that Britannia ruled the waves, or at least a small portion of them. No ship could pass conveniently between Europe’s great ports and the Panama Canal without coming under the unseeing scrutiny of a lighthouse that belonged, firmly and for the foreseeable future, to Britain.

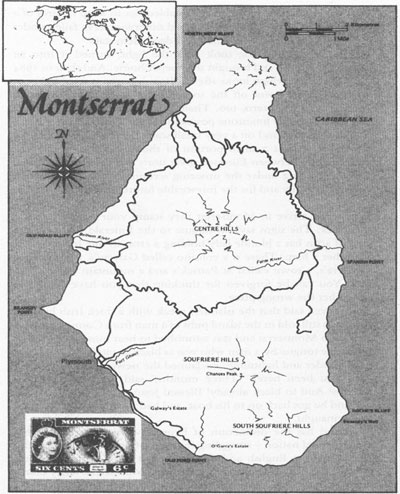

When you arrive in Montserrat they stamp your passport with a shamrock. The signs say, ‘Welcome to the Emerald Isle’, and the coat of arms has a blonde lady holding a cross in one hand, and in the other a harp. There is a volcano called Galway’s, a farm called O’Garra’s, a town called St Patrick’s and a mountain called Cork Hill. You can be forgiven for thinking that you have landed in altogether the wrong place.

It is even said that the islanders speak with a thick Irish brogue. A story is still told in the island pubs of a man from Connaught who arrived in Montserrat and was astonished to hear himself greeted in his native tongue by a man who was as black as pitch.

‘Thunder and lightning!’ exclaimed the newcomer. ‘How long have you been here?’ ‘Three months,’ said the native. ‘Three months! And so black already! Blessed Jesus—I’ll not stay among ye!’ and he got back on to his boat, and had it sail all the way home to Connaught.

Ireland has the distinction of being known as a redoubtably anti-Imperial nation—struggling for most of her history against the rapacity of the English and the Scots. But early in the sixteenth century the Irish did colonise the island of Montserrat. They didn’t discover it—Columbus did that, in 1493, and named it after a

Catalonian monastery, because he thought the rugged hills and the needle-sharp peaks looked similar to the mountains beyond Barcelona. (The monastery of Santa Maria de Monserrate was where Ignatius Loyola saw the vision that prompted him to form the Jesuit movement—the island’s name thus seemed an ideal refuge for Catholicism.) But the Spaniards made no attempt to annexe the little island, and it was left to Irishmen, in 1633, to take the place over.

They did so precisely because the name suggested refuge from the intolerance of Protestantism. There were Irishmen in Sir Thomas Warmer’s newly growing colony on St Kitts—but Sir Thomas was a bluff Suffolk squire, not particularly eager to mingle with wild Irishmen, and he made life difficult for them. A party left by boat, and were blown by the trade winds to an island in which they saw ‘land high, ground mountainous, and full of woods, with no inhabitants; and yet there were the footprints of some naked men’. The countryside was fertile, the weather pleasant, and, best of all, the place even looked like Ireland. So they named their landfall Kinsale Strand, and set about making the island into a new Irish home.

For a while it became a sanctuary. Irishmen arrived from Virginia, where the Protestants were busily establishing an ascendancy in that new colony; and they came from Ireland, too, once Cromwell had started to busy himself there. By 1648 Montserrat had ‘1000 white families’—all of them Irish. There was an Irish Governor named Mr Brisket, and the islanders were eating Irish stew, which they called—and still call—goatwater. Montserrat goats are said to have flesh tasting like the best of Galway mutton. (‘Mountain chicken’, another local dish, is actually breadcrumbed frog.)

But charming though the idea of an Irish Caribbean colony might have been—think of the mournful ballads that might have been sung under a summer’s moon to the lilting music of the harp and the steel drum, or the sad sagas of the O’Flahertys’ sugar mill, the tales of Irish tobacco and Irish rum, the hurricane shelters at the shinty matches—it had not the wit to last. The Irish tried cunning, and it failed. They formed an uneasy alliance with the French,

hoping that they might together drive the English out of St Kitts. But the English kept hold of St Kitts, and drove the French—who by this time had taken over Montserrat completely, having merely made use of the Irishmen—out of the area totally. Three years later, in 1667, the French were back, but then the Peace of Breda was signed, and England was given the island in perpetuity.