Outposts (33 page)

The linear distance between Road Town and The Valley—British colonial capitals have the most wretchedly prosaic names!—is almost exactly 100 miles. It took me six hours, via aircraft, car and speedboat. First, I flew from Beef Island to the island of St Kitts, the first West Indian island to be colonised by Britain with, confusingly,

a capital with the very non-British name of Basseterre. After a cup of coffee at Basseterre airport matters became more confusing still. The plane, which was so small it looked more suitable for entomology than for aviation, turned back northwards to the extraordinary island of Saint Martin—extraordinary because the island’s southern half, where the plane landed, is still run by the Dutch under the name Sint Maarten, and the northern half is run by the French. Technically it is French, an

arrondissement

of Guadeloupe. It sends deputies to Paris, has a prefect, and its

citoyens

are as French as if they were born in Marseille.

I landed at Queen Juliana airport, was checked by a dour Dutchman who stamped my passport, took a taxi via a dusty little hamlet called Koolbaai—in fine rolling countryside; it reminded me of Cape Province, and the hills near Stellenbosch—and was driven up to the frontier. I would like to have seen a red-and-white pole, members of the

Staatspolizei

on this side, kepi-wearing

gendarmerie

on the other, but there was only a boundary stone and a couple of flags that I had great difficulty telling apart (both having the same colours, the one being horizontal, the other vertical). There was no one to look at my passport, but when, eventually, I was taken to the

quai

at the French capital of Marigot—after a quick snack, some shrimp, half a baguette, and a glass or two of chilled Sancerre—and found the boat to Anguilla, I was duly inspected, my bags checked and a stamp affixed, all with great Gallic flourish. The boat, driven by a pair of excitable youths who appeared to have had the odd glass or two of Sancerre as well, took off northwards at about sixty knots. We rose out of the water, and seemed to fly. The service, I learned later, was by hydrofoil.

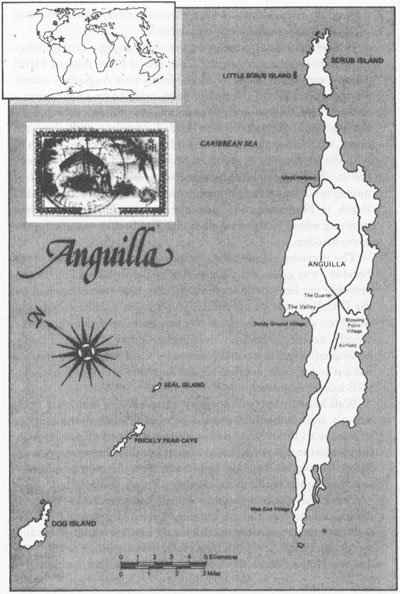

Anguilla lay low and white on the water, like a submerged whale. It is a long, narrow island with no hills, except for a 158-foot peak on the eastern tip, named Navigation Hill because of its use as a sea mark, and a 200-footer in the middle. The island’s axis lies parallel to the ever-wafting trade winds, which is said to be the reason there are no forests, and little rain: the winds just divide and waft on, leaving nothing (whereas on Tortola they are forced up, form clouds, and burst out with rainstorms). From afar Anguilla looked

strangely empty and lifeless. Sand beaches glittered brilliant white, with a line of low palms beyond. A tiny blue yawl bobbed at anchor by the pier. A Land Rover arrived, scrunching over the coral pebbles. The immigration inspector, wearing the crown of office, welcomed me ashore. ‘Not too many people come by sea and stay,’ he said. ‘Nice to have you here. Rare thing.’

Anguilla is Britain’s newest inhabited colony—new in the sense that, while it has been British territory, and in the cadet branch of far grander West Indian possessions for many years, it has only lately been a colony in its own right. (The very last piece of real estate that was subsumed into the Empire was actually the island of Rockall, out in mid-Atlantic, in 1955. London felt it vital to annexe the lonely chunk of guano-crusted rock because, just perhaps, it might have oil nearby; so it ordered out the Royal Navy, and matelots clambered up the slippery cliffs and fixed a brass plate to its granite summit. An expedition went there a few years later, and found the plate had been unscrewed, and taken away. Britain still claims Rockall, though, brass plate or not.)

Anguilla—or ‘Malliouhana’ as the Caribs named it—was formally made into a Crown colony and given a constitution, and a fully-functioning governor, in December 1982: she thus became the last colony 399 years after Britain took her first, Newfoundland. The reason for the establishment of a new colony—bucking the trend of twentieth-century decolonisation in no uncertain manner—has much to do with Operation Sheepskin, and the events that led up to it.

Anguilla has always been a poor island. The soil is thin, the rainfall scarce, the possibilities for livestock or agriculture minimal. There was precious little that the Britons who settled there could exploit, and very little work that their slaves could do for them. Across in Barbados, or down in Montserrat there was sugar to cut, or limes to pick, or tobacco to cure. In Anguilla there was nothing, and the slave-owners took a decision that was to have far-reaching consequences. They gave their workers four days off each week—the Sabbath, as was customary, and three other weekdays to allow

them to cultivate their own patches of thin ground. When the Britons departed, for more fecund islands, and for their old home, the slaves that remained were more accustomed to working their own land, more familiar with the idea of freedom—even if it had only been of the four-day-a-week variety, it was more than their fellow slaves in the neighbour islands.

Thanks to this oddly gifted freedom, the ability to till land that was their own, and finally the hasty departure of the uninterested Britons, so the Anguillians, uniquely among the Leeward Islanders, evolved a rugged kind of independence. They proved awkward to rule, eager to mind their own business, and would brook no nonsense from any colonial master. In 1809 the Government told the Anguillians to build a prison at The Valley; yes, they replied, they would build one if and when they had anyone to put in it. And not before.

They had their own government, known as the Vestry, with four nominated members, and three elected. A dull little place, maybe, but it had rudimentary democracy earlier than most—another good reason for the islanders to feel determined, and a little aloof.

All raiders were repulsed. The French tried twice; the first time, in 1745, they were driven off at the battle of Crocus Bay by sheer mass of numbers, and number of island cannon. On the second occasion, fifty years later, the Anguillians showed gentlemanly restraint: the French powder was damp and, thinking they were out of the islanders’ sight, they spread it out on sheets to dry, right along the beach at Rendezvous Bay. The islanders planned to toss burning staves at the powder, and blow it up, but their leader said that would neither be fair, nor British, and so they melted down all their fishing weights, made new bullets and fired away at the French with those, and drove them off, too. A determined, indefatigable people.

The British failed to recognise this ‘passionate devotion to independence’ when they came to organise the colonial arrangements for the region. No thought was ever given to creating Anguilla as a separate presidency, able to run itself under the general invigilation of the Leewards’ Governor. No suggestion was made that Anguilla

be linked with Tortola, which was at least notionally in its line of sight. Instead, for some unfathomable reason, Anguilla was formally linked with—and run from—an island a hundred miles to the south, separated from it by four other groups of islands that were run by the Dutch and the French, and peopled by natives whom the Anguillians cordially loathed.

The British, for administrative convenience, chose St Kitts to be the titular head of the presidency—it was called St Kitts-Nevis-Anguilla, and under the new arrangement Anguilla was very much the junior partner. The medical officer now ran the island, and doubled up as the beak; one Anguillian was sent to St Kitts to represent the island on the council; there was never enough money to build proper roads or a decent airfield, and there never was a secondary school, although the other islands shared four.

All this was just bearable so long as the British remained in power. The essential fairness of the Colonial Office and of the British establishment in St Kitts meant that the Anguillians were at least reasonably well provided for. But in 1967, after lengthy negotiations in London, St Kitts-Nevis-Anguilla became an independent nation—day-to-day rule over Anguilla moved from the British to the detested men of St Kitts. The Kittitian who was in the unhappy position of being his Government’s official representative in The Valley on Independence Day decided to make as little fuss as possible: he got out of bed at four, raised the independence flag in his living room, saluted it while still in his pyjamas, and then crept back to bed.

One man in particular, the St Kitts’ Chief Minister, Robert Bradshaw, became the focus of Anguillian venom. Hardly surprising, perhaps: he had once publicly vowed to ‘turn Anguilla into a desert’. The islanders threw out his police force (there was not a single Anguillian policeman) and called in a motley crew of advisers—mostly Americans, and not always men of the most savoury reputations—to lead them to the state that Rhodesia had recently adopted: a Unilateral Declaration of Independence.

The Anguillian leader, Ronald Webster, and a remarkably colourful and patriarchal figure named Jeremiah Gumbs pleaded

their case to the world. Mr Gumbs appealed before the General Assembly of the United Nations. Over in St Kitts Mr Bradshaw, who drove around in a vintage Rolls-Royce, appealed to the British to whip the Anguillians into line, and to halt the unseemly rebellion.

A parade of British officials came and went—one of them being brusquely turfed out because the Anguillians thought he was rude. He felt he was in danger of being lynched, so he gave an emergency message to the local Barclays Bank manager, who smuggled it through the islanders’ lines in his shoe: the note was addressed to SNOWI—the Senior Naval Officer, West Indies, and asked for help.

In an act which half the world thought amusing, and which to the other half indicated that Britain was still an Imperial bully-boy, London decided to send in the troops. The second battalion of the Paras was alerted and sent to a holding base at Devizes. Forty policemen, members of the Metropolitan Force’s Special Patrol Group, were kitted out in tropical uniforms (though not all of them; their leader was reckoned too fat for any of the cotton drills to fit) and joined them.

Fog delayed the group at their airfield in Oxfordshire, and Fleet Street found out all about Operation Sheepskin. Reporters met the plane in Antigua—a foolish place to land, since the Antiguans liked what the Anguillians were doing; they expressed their irritation by tossing out their Prime Minister in the following year’s election, saying he had ‘connived’ with the British.

The troops and the policemen were put on the

Minerva

and the

Rothesay

, and left for the high seas. The reporters chose to invade at greater speed and in greater comfort: they flew across to Anguilla and waited. At 5.19 a.m. on the 19th March the first of the Red Devils landed. A series of blinding flashes greeted them as they reached the beach, and, as per their training, they threw themselves to the ground. They needn’t have worried. Fleet Street was merely photographing the landing, for posterity.

Ronald Webster had no idea there would be a landing by British troops. He was in the bath when they arrived, and first got to learn of the invasion from a reporter, who asked him what he thought of

it. Others were more prescient. An American lady confessed, with characteristic candour, that she had ‘spent the entire night in my brassiere to be ready for the invasion. I never did that before in my life.’

If there were an armed rebellion brewing in a remote British possession, they never found the arms. Four old Lee-Enfield rifles, not very well oiled, and securely locked up, seemed to represent the total armoury. (It was later suggested that the rebel leaders had buried the guns in the mountains of Saint Martin, but they have never been found.) A few people were arrested and taken off to the warships for a little talk. Some reporters said a shot had been fired at a plane they had chartered, but it was probably the perfervid imaginations of Fleet Street at work. In fact the little war must have been the most peaceful ever prosecuted, anywhere; and it made Britain look very foolish indeed. ‘The Bay of Piglets!’ jeered one American headline. ‘The Lion that Meowed!’

The Imperial power was made to look even more ham-handed a few years later, when Anguilla and her ‘rebel’ leadership were formally offered every last thing they had wanted. They were not forced to join up with St Kitts and Nevis. Kittitian policemen, and Englishmen who wanted Kittitian policemen, were not foisted upon the islanders. The island was given back its own parliament—larger than the Vestry, and with greater powers. And the British Government happily prised the island away from Mr Bradshaw’s clutches by making it a Crown colony (although, with the word ‘colony’ no longer thought proper, the actual technical term used was British dependent territory). The senior Briton dispatched to run the place was no longer to be called a medical officer, nor a resident, nor a senior British official, nor an administrator, nor a magistrate, nor a commissioner: from 1st April 1982, thirteen years and two weeks since the arrival of the two tiny warships off Crocus Bay, Anguilla could relax under the benign rule of Her Majesty’s representative, His Excellency the Governor, complete with white uniform, sword and a splendid hat, gold braid and feathers, all entwined. Nothing so grand had ever been seen.