Outposts (36 page)

So I walked up the hill, through the steel gates and the welcoming signs, and made for the bar. The ballroom next door opened out on to a terrace, which overlooked a still and silent sea. Inside the

ballroom a band from Antigua was playing reggae music. Its leader, in red-and-yellow blazer, was doing his best to lighten the atmosphere of the place, giving encouraging smiles and imploring some of his audience to come on to the floor and dance.

But no one wanted to dance that night. Nor any night, I suspected. There were about twenty people in the room. Each was slumped back in an armchair, peering wanly at the band through eyes that were heavy with sleep, or narcotic drugs. Behind most chairs was a steel rod from which was suspended a bag of saline solution, a plastic tube carrying the liquid to each bandaged arm. One or two tapped fingers, or toes, to the rhythm. There was a strong smell of garlic, and when one of the ‘guests’, a woman in her fifties, saw me wrinkle my nose, she beckoned, and whispered an apology.

‘I’m sorry about the smell. It’s the drug—the dimethyl stuff. It goes through you so fast, and leaves this garlic smell. I guess it’s bearable if you know the stuff is doing you good.’

And was it? She thought so, yes; she had put on three ounces in the first week she had been a resident, more than she had put on in the last month back home. She was no more than a bag of bones, her face was drawn and grey, her skin was translucent, yellowish, like parchment. She wasn’t fifty at all: she was thirty-two and she had had cancer for a year. The visit to Montserrat was costing her three thousand dollars a week, and she was sure it was doing her good. An elderly man—or was he young?—in the next chair nodded his head in vigorous agreement. ‘You tell ’em, Sal. You are getting better, sure you are.’

But Sal wasn’t getting better. She died two weeks later on her way home. She was an ounce heavier on departure than when she arrived; she had spent nine thousand dollars. Perhaps she had been given a measure of hope, and considered her money well spent. I couldn’t help but feel a sense of distaste, even anger; and most Montserratians loathe the clinic, and wonder how the Government ever allowed it to open for business. ‘The death house on the hill’ was how I heard it described down in Plymouth.

Six years ago the politicians in Plymouth were ruefully contemplating an indefinite future as a colony. ‘The Last English Colony?’ was the title of a pamphlet published in 1978, and there was a general acceptance that, as it said, ‘Montserrat will probably be a colony long after Britain has shed all her other responsibilities.’ But after the American invasion of Grenada the perspective shifted. The Montserrat Chief Minister became chairman of a local power bloc, the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States; he asked if he could send a token force of the Royal Montserrat Police to Grenada, and Britain said no, he couldn’t, since Britain was keeping strictly neutral and expected her colonies to do so as well.

That did it. Why, the Chief Minister asked, should Montserrat be subject to ‘the overruling and sometimes myopic colonial power’ any longer? Was it not embarrassing and degrading? Should not the islanders accept ‘the dignity of managing their own affairs’? He said he would be formally requesting independence from Britain; the Foreign Office, with the languid superciliousness for which it is renowned, simply replied that it was unaware of any request, but would study the matter in due course. And there the matter remains.

For the politicians doubtless the independence of Montserrat is of crucial import. For the islanders I suspect it is, and will be for some time, a matter of less immediate moment. They are as unhurried and untroubled a people as any in the West Indies, without much undue passion, without a burning sense of injustice or a pervasive feeling of subjection.

Perhaps it has much to do with their Gaelic spirit. As a local columnist once wrote, from old Sweeney’s sugar estate in the north to O’Garra’s deep down in the south, this truly is ‘our Ireland in the sun’. Every bit as content to be under the rule of Whitehall, or Plymouth, or even Dublin all over again.

There have been many government committees in Whitehall, and most of them have been deservedly forgotten. The people of the Cayman Islands, one of the wealthiest and most successful of British colonies, have good reason to remember, and indeed raise a glass to one of them—a committee which is generally regarded as having

been a total failure, and which only stayed in existence for six years.

The Colonial Policy Committee was set up in 1955, by Sir Anthony Eden. Its avowed purpose was to suggest to the Cabinet how best Britain might accomplish the running down of Empire, and how the country might treat those colonies that remained; it was the body Sir Winston Churchill had meant when, some years earlier, he had said that the Colonial Office would have so little work to do that one day ‘a good suite of rooms at Somerset House, with a large sitting room, a fine kitchen and a dining room’ would be most suitable for the direction of Empire.

The CPC—with the Colonial Secretary, the Commonwealth Secretary, the Foreign Secretary and the Minister of Defence meeting under the chairmanship of the Lord President of the Council was a flop. The Cabinet complained that it never got any direction from the Committee; the Committee complained that it was bogged down in sorting out day-to-day problems, and never had an opportunity to make exhaustive analyses of Imperial policy. It was abolished in June 1962, and nobody appeared to miss it.

But lacklustre though its overall performance may have been, the Committee enjoyed a spectacular success in what was almost the last decision it ever took. On 30th March 1962 it accepted the advice of the then Colonial Secretary, Reginald Maudling, and agreed that the Cayman Islands should be detached from the colony of Jamaica, which was then about to become independent, and become a new Crown colony, on their own.

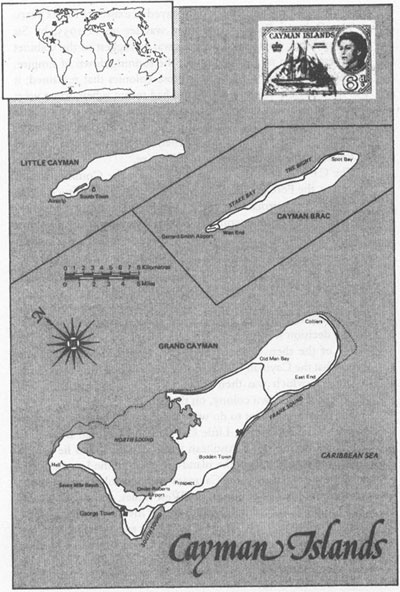

The reasons had a lot to do with geography. The three Cayman Islands—Grand Cayman, Little Cayman and Cayman Brac—are tucked below the Great Antillean island of Cuba, and lie several hundred miles away from the island-arc chain of the Leewards and the Windwards. Jamaica, the Caymans’ mother-colony, was in 1962 a member of the Federation of the West Indies, and the Caymans, having nothing in common with the other members of the Federation, wanted to pull out. There is an almost exact parallel between the Caymanian attitude to the Federation, and Anguilla’s hostility to St Kitts—in the case of Anguilla, Britain sent troops to try to stop the impending rebellion; in the case of the Cayman Islands the

Colonial Policy Committee agreed that no islander should be forced to join anything he didn’t want to. So the recommendation was made that the Caymans become a separate colony, with loyalty neither to Jamaica nor to the West Indian Federation (which in any case collapsed in an ugly shambles shortly afterwards), but only to the distant figure of the reigning British monarch. The full Cabinet agreed with the Committee, and so with cap-and-feathers, sword-and-spurs bought, Government House duly built and a suitable colonial servant duly appointed (at first styled ‘Administrator’, but a full-fledged Governor after 1971), the colony got shakily under way.

It has proved to be a quite extraordinary financial success—perhaps, in purely monetary terms, the most successful little country in the world. It is a success measured solely in numbers, maybe; the place has little charm, and even less culture; but in numbers—and that essentially means numbers of dollars—its triumph is unchallenged.

The islands are flat and, save for a modest hillock on Cayman Brac (‘brac’ is a Gaelic word for ‘bluff’, which on this islet is just 140 feet high), they are utterly featureless. Columbus spotted them in 1503, but decided not to bother landing, as they looked so uninspiring: he named them Las Tortugas, because of the enormous numbers of green turtles in the surrounding seas. They were renamed Las Caymanas because of the similar abundance of sea-crocodiles; but there are no crocodiles left today, and many islanders wish for the old name back, as the place still crawls with turtles.

The islanders—a mongrel mixture of races and nationalities, pirates and deserters, freebooters and buccaneers, a crew who knew no racial divisions then, and, almost alone in the West Indies, appear to harbour none today—built mahogany schooners, fished, and fattened turtles for export. But it was a poor living, and in the early years of this century hundreds left, to go to Jamaica, or even to Nicaragua, which lies temptingly close to the west. In 1948 there was just one bank on the island, and a collection of shanty towns and peasant farmers: the exchequer took in only thirty-six thousand pounds from the 7,000 inhabitants. They exported 2,000 turtles, at about three pounds a time; the total export income was twenty

thousand pounds, and the Administrator had control of a Reserve Fund of thirty-eight thousand pounds, and a Hurricane Fund of two thousand. The soil was too thin to farm; the islands swarmed with mosquitoes, with dengue fever and yellow fever occasionally breaking out as epidemics; there were brackish swamps, acres of scrub and casuarina, and a few thin cattle. The Cayman Islands were a long way from being the brightest star in the Imperial firmament.

But a genius was waiting in the wings. Vassel Godfrey Johnson, a slender, bespectacled Jamaican whose family came from Madras, was a civil servant in the Finance Department in Jamaica. He came to Cayman during the debate over whether or not the island dependency should join the Federation; and, when it was decided that they should in fact become a new colony, separate and self-standing, he hit upon the solution that has since made the Caymans one of the wealthiest places on earth.

He explained that he had a sudden idea: since the islands were too poor to pay taxes, and since they were in the enviable position of being a British Crown colony, with all the stability and protection such status conferred—why not offer freedom from taxes to anyone who wanted to invest money on the islands? Why not encourage businesses to come and place their headquarters on Grand Cayman, and shelter themselves from the burdens of taxation they might face elsewhere? Why not offer secrecy and discretion, and make the islands into a Little Switzerland-on-Sea?

Mr Johnson worked for months, studying legislation and banking regulations, persuading the Jamaican Government, and then the Cayman Administration and the supervisors at the Foreign Office, that all would be well. By the time full colonial status was achieved the legislation was in force. The mosquitoes had been wiped out, too—Vassel Johnson had decided that bankers would not come to Grand Cayman if they were going to be made the subject of a Torquemada’s feast as soon as they stepped off the plane—and the colony was ready to receive its first millions.

It all took a little time. Bankers were reluctant to divert their monies from Zurich; American investors were content to keep their funds in Nassau, 500 miles north, in the Bahamas. There was a

natural reluctance among this most cautious of communities to set down with funds in a new and untried country—British colony or not.

But then came the independence of the Bahamas, in 1974. The bankers were content with the Prime Minister whom the British left in charge; but within a year there were audible stirrings of Socialist opposition in Nassau, and the back streets were displaying posters calling for the nationalisation of the banks. Caution vanished; alarm took over; and banker after banker packed his suitcase and headed south, for Grand Cayman. Barclays Bank went first; and then a trickle, then a stream, and then a tidal wave. Banks from all over the world, from Winnipeg to Waziristan, set up shop in George Town.

The Yellow Pages in the Cayman telephone book lists six pages of banks, from the Arawak Trust (Cayman) Limited, to the Washington International Bank and Trust Company. Billions of dollars are invested in more than 440 banks registered in the Cayman Islands; and there are 300 insurance companies, dozens of world-class accountants, and more than 17,000 registered companies—one for every inhabitant. Outside the offices of most lawyers in town are long noticeboards listing the names of each and every company registered with the firm: pretty secretaries can be seen every day adding new plates to the list as fresh companies send in their government registration fee (of eight hundred and fifty dollars, minimum) and commence operations under the benign and liberal style of Caymanian protection.

Now, from a sleepy mess of mangrove swamps and seagrape trees, the Cayman Islands have undergone an amazing and breathtakingly rapid evolution. There are now more telex machines per head of population than anywhere else on earth; there were, in 1980, more than 8,000 telephones on the islands—one for every two people, and almost as many per person as in Britain. Satellite dishes have spawned like mushrooms all over the islands—when I met Vassel Johnson we did, indeed, sit under a seagrape tree beside the ocean, and there was driftwood on the beach and the sea shimmered in the late afternoon sun; but beside his house was a great white dish

pointed up at Satcom Three, and he could receive fifty-three channels of television, twenty-four hours a day. He had a Mercedes and a motor cruiser, and there was a badminton court next to his bungalow. The standard of living he enjoyed was not, by island standards, particularly remarkable: but there was no poverty on Cayman either, and none of the shabbiness I had encountered on Grand Turk, or on Anguilla, or Montserrat.