Oxfordshire Folktales (25 page)

Read Oxfordshire Folktales Online

Authors: Kevan Manwaring

![]()

T

HE

K

ING

UNDER

THE

H

ILL

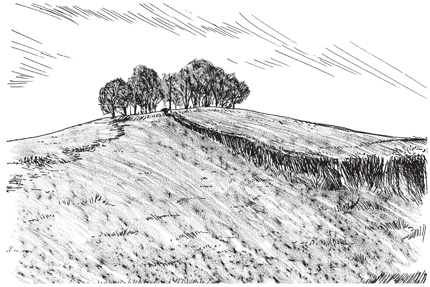

Scutchamer Knob has always been an uncanny place – a moot for ghosts, a place of old sorcery. Hidden within a small copse next to the ancient Ridgeway, running by the parish of East Hendred, it stands: an earthen mound, a burial mound – some say of the Saxon King, Cwichelm. Long has it been believed that the King under the Hill lives there still, waiting to rise up once more…

Despite his ‘lordship-in-residence’ – as locals would refer to the Barrow King, doffing their cap to the Knob (‘because you never know’) – a market would take place there once a year. It was a crossing way which was handy for many a traveller along the high roads. This was a chance to share news and views; barter and trade; woo and box; purchase charms and shoe horses; and pass on the luck. Some, though, like to keep the luck to themselves.

That lot over at East Ilsley weren’t happy about that market at the Knob. Since they were granted their charter in 1620 for their own fair, they’ve acted all high and mighty and petitioned to have the Barrow Fair put down. And that was that. The hill fell silent.

But still some met there by moonlight – for a different kind of market: a market of magic. There, by flickering campfires, the old tales would be brought out and polished up with a bit of breath and shirt-cuff. The old way-tellers, as gnarled as blackthorn cudgels, would spin you a yarn for a quart of ale, or a thumb of baccy.

They would talk of the King under the Hill. How he once strode the land, tall and proud in his shining arm-torcs, buckles and scabbards – one of the Kings of Wessex. How he fought off those Raiders of the North many a time. Here, right here, on this very spot, he stood his ground. There was a prophecy that if the enemy ever made it up the hill, they would never take a ship from England again. And so, when the Danes struggled uphill to camp here in 1006, Cwichelm and his men killed them – every one – stone dead. The good green grass ran red, red, red with blood. Cwichelm wiped his sword with the hem of his cloak and smiled a grim smile; more carrion for the Crow-father.

In his life he had slain many men. In 614, at the Battle of Beandun, did he not slay two thousand and forty-six of the Strangers-beyond-the-Dyke – fighting side-by-side with his fellow King of Wessex, Cynegils? Together they fought King Penda at Cirencester. Those were the glory days. Nothing could stop them when their swords were drawn as one.

Other times were less than glorious, like when he attempted the assassination of King Edwin of Deira. The cut-throat’s way was the coward’s victory. His conscience did not feel clean until he was washed in Christ’s water at Dorchester – in

AD

636 – the same year he died.

To this hill of victory he was brought and to his kin and men a barrow raised.

Here, beneath this very mound, the Barrow King remains until his might is needed again. While he sleeps the grass grows on his back; trees guard his bed – Cwichelmslaewe it was called, in the old tongue. Time wears down words as they are rolled about in the mouths of men, like well-thumbed coins, and over the years it became known as Scutchamer Knob.

The tellers would fall silent then, ending with a toast to the King under the Hill for luck. It’s wise to keep the dead happy. They like to hear tales of themselves. They are good listeners.

![]()

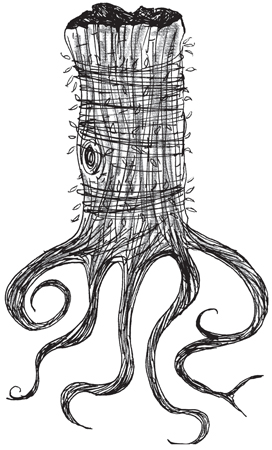

Scutchamer Knob was excavated in 1842 in a rather brutal fashion, hence its current crescent moon shape. The dig discovered the moot-stake – an oaken stump bound with willow twigs. Cwichelm existed and gets several mentions in

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles

. He was a king of the Gewisse – a people in the upper Thames area who later created the kingdom of Wessex. The market at the barrow did used to take place, and the local belief was Cwichelm was buried there. He joins an exalted company of chthonic kings, including, of course, King Arthur. It was a meeting place and a place of magic and still has a strange atmosphere to this day. From these scraps I have stitched together this tale.

O

LD

S

CRAT

IN

O

XFORDSHIRE

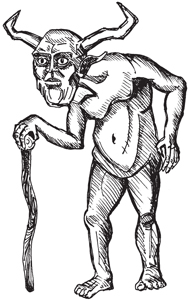

The Devil, or Old Scrat as he’s known around these parts, liked to visit Oxfordshire as much as any county in the land. For some reason, he took a special shine to North Leigh. It was a well-known fact in the area that Hill Farm was haunted by the Lord of the Flies himself – as well as having more than its fair share of ghosts – despite having a priest’s hole in it (although perhaps the priests themselves perpetuated the legend to keep unwanted visitors away). One man who lived there became suddenly rich and it was commonly believed he had found the ‘ghosts’ treasure’. Another local, Jack Adams, claimed to have seen Old Scrat himself by Hill Farm, describing him as ‘all spotted and speckled’, so the saying arose locally: ‘all spotted and speckled like Jack Adam’s Devil’.

Old Scrat was fond of appearing to North Leigh Sabbath-breakers. If anyone went a-nutting on a Sunday, he went with them, helping them by pulling down the branches within easy reach. At the water-pump, the old wives would mutter: ‘Nutting is always a chancy past-time and those young girls do indulge in it to the hazard of their maidenhood!’

One day, some men caught a badger and put him in a sack, but on the way home it disappeared, leaving a strong smell of brimstone – so even old Brock was accused of being Old Nick.

Once, some boys were playing Sunday cricket on the common when a stranger appeared and offered to join in – he was an excellent player, but at the end of the game, he vanished in a puff of smoke.

In the churchyard there’s a tomb with a hole in it on the north side of the church – the Devil’s side (most churches have a Devil’s gate on that side, look next time and you’ll spot one). Anyone foolish enough to run around it twelve times and look through the hole – well, what do you think they will see? Old Scrat peeping back at them, of course!

Sometimes, he appears to you when you don’t want him to. Once, a man was walking from North Leigh to Barnard Gate, when the Devil came to him in the shape of a fiery serpent – wrapping itself around him and trapping him for hours. When he was finally able to escape he ran back to North Leigh to get help. He returned with a group of men to the very spot he had been pinned down: ‘Here it was, right here!’ but the serpent had long disappeared. He’s a slippery customer, Old Scrat!

A similar thing happened to a couple of fellows in Swinbrook. Drinking buddies, they were walking back from The Swan Inn, up along the lonely back lane that crosses Ninety Cut Hill. It was a bright moonlit night, the stars were out and their spirits were high. They were having a good old chat, when for some reason they both fell silent at the same time and came to a dead stop. Before them was something jet black and about the height of a piano. Then it changed into a column about the height and shape of a man, a man made of smoke. Frozen in terror, they watched as it moved in a zigzag motion before them, first this way, then that, like a frightened dog – though the men were the ones whimpering. It seemed to want to get by. One of the men pulled out a torch and flashed it at the thing, but there was nothing there, only withered undergrowth by the roadside. Laughing nervously, the men carried on. Later, they discussed it, safe and snug inside, and agreed they had seen the same thing. One reckoned it was a ghost but the wiser of the two knew who it was alright: Old Scrat, that’s who!

But Old Scrat gets some bad press – sometimes he wants to help. Take for example the three churches of Adderbury, Bloxham and King’s Sutton, famed for their elegant spires – the tallest parish churches in the county. They were built by three masons who were brothers; Old Scrat turned up to give them a hand as a labourer. The brothers kept him busy, running back and forth. He got tired, and one day he fell down with a load of mortar and so made Crouch Hill. An old saying goes:

Bloxham for length,

Adderbury for strength,

and King’s Sutton for beauty.

Nobody thanks Old Scrat for them. There’s no sympathy for the Devil in Oxfordshire.

![]()