Oxfordshire Folktales (27 page)

Read Oxfordshire Folktales Online

Authors: Kevan Manwaring

With an expressionless face she showed them every room. The Captain carefully watched for a reaction, a clue – but her mask gave nothing away.

They hunted for the rarest of game, a ‘Royal stag’ – the fleeing King himself – or so they thought.

Finally, they came to the Cavalier Room and searched it thoroughly. Mrs Jones feigned nonchalance as the Captain scrutinised her.

Arthur kept silent behind the screen, terrified of making a noise and being discovered.

Finally, they finished. ‘Nothing, sir.’

The Captain gritted his teeth.

‘Would your men be wanting a bed for the night?’ the Lady of the Manor asked, the ghost of a smile on her lips.

‘Yes,’ barked the Captain. ‘We’ll take this room. Send up some supper.’

‘As you wish, Captain. I hope you’ll find the accommodation to your liking.’

Mrs Jones fixed their refreshment herself, mixing laudanum with their wine. She had a servant bring it up on a tray.

The soldiers were thirsty after their day of battle and hard-ride. They knocked the wine back, their boorish laughter echoing through the house. For a while, it was unbearably noisy. Then it fell strangely quiet.

Mrs Jones ventured upstairs to the Cavalier Room. The door was ajar and from within she could hear loud snoring. Sprawled across the room were the whole company – fast asleep.

‘Sweet dreams, Captain,’ smiled Mrs Jones.

She gave the all clear and one of the tapestries twitched. Timidly, her son appeared. She placed a finger to her lips, and then signalled for him to follow. Tiptoeing between the sleeping soldiers, Arthur Jones slipped away before his mother led him, business-like, to the stables.

‘Take one of the horses and ride as far away as it will carry you.’

‘But, what about you…?’

‘Don’t worry about me. I can handle them. Go!’

Arthur reluctantly mounted the fastest looking horse and blew his mother a kiss, before digging in his heels. With a whinny, the horse burst from the stable and galloped into the night.

In the morning, the soldiers awoke, groggily, to discover one of their horses mysteriously absent, and their ‘Royal’ prey vanished like the dew.

The Captain roared at her.

‘The horse, where is it?’

Mrs Jones feigned innocence. ‘Perhaps you misplaced it, like your wits.’

‘Lady, you overstep your mark!’

‘Why sir, if you cannot handle yor wine, whose fault is that but your own?’

The Captain clenched his fist. ‘You will pay for harbouring a wanted criminal!’

‘Lower yourself to threaten a woman if you must – such is the greatness of your cause – but may I remind you that all the while your Royal stag is getting away…’

The Captain glared at her. ‘Men, saddle up. We ride.’

‘Farewell, Captain. I would like to say what a pleasure it’s been having you as my guest…’

Furious, they galloped off.

They never caught Arthur, and the Lady of the Manor survived the Civil War with her splendid demesne intact. And so, Chastleton House still stands to this day, in all its glory – a deceptively peaceful corner of England.

![]()

Chastleton House was sold to the Jones’ by a certain Robert Catesby. It would appear he used the sale of the property to help fund the notorious Gunpowder Plot. So, its fortunes have been balanced between Parliament and Crown. Somehow it has survived the vicissitudes of history, and these days’ looks like the very bastion of English respectability and peaceful, well-heeled status quo, sitting comfortably in its leafy vale. Yet the walls remember the time the Lady of the Manor hid a ‘Royal stag’ and defied the Puritan Lord Protector, Cromwell.

T

HE

A

NGEL

OF

THE

T

HAMES

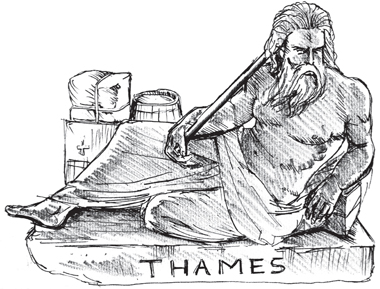

Old Father Thames they call me; a strong brown god – how wrong the poets were; how right. Look at me snaking sluggishly through London, like a bloated anaconda – one that had swallowed a city, and it would be easy to agree. Silently, I carry the sins of the citizens; receive them all like a brown-robed priest taking confession, offering forgiveness and sometimes sprinkling them with blessings – showing them a glimpse of grace.

In recent years, there have been several sightings of me: a TV presenter, on camera, caught a glimpse; a group of Korean students posing for a photograph; day-trippers; dog-walkers; down-and-outs; and the high and mighty. All are ignored or mocked with laughter. They say they are seeing what they want to see. They have seen the dodgy footage on You-Tube, on questionable websites, and convinced themselves that that flash of light caught in the corner of the eye, that faint smudge in the background of a holiday snap, that blink-and-you-miss-it blur on the shaky camcorder shot, is an angel. It is easy to see why sceptical folk scorn such digital delusions. An urban myth, the folklorist might call me: a psychologist’s field day.

They do not hear my screams. They do not hear a river crying. My beautiful smooth body filled with your toxic waste, your sewage, your oil. What once flowed clear – innocent as Spring – from its source, turned dark with the silt of humanity, so that I fulfil my name, ‘dark flow’. Once, in Victorian times, I became so polluted that the Houses of Parliament were closed down: the Great Stink, it was named. Ironic, since it is usually from Westminster – the fording place – that such noisome odours emerged.

I was dying.

But nature can be kind, and several severe winters killed off the diseases that ravaged me. I froze and they held Frost Fairs on me – stalls and side-shows offering every kind of gewgaw and mountebank, great marquees filled with Nine-day Wonders, sled-rides and spit-roasts, imagine! Children, playing in my garden. My heart melted and I forgave them.

I am old; I have seen too much to hold on to anything for long. It is all water under the bridge.

Forgive me. I am prone to meander. Occasionally, in my super-annuated twilight, the estuary of my existence, I have been known to bitter outbursts.

But once I was young and sprightly.

Let me take you back to my beginning, to my source.

In a peaceful meadow in Gloucestershire I begin, quietly and modestly. Like a shy maiden I can only be glimpsed fleetingly. My waters rise at certain times of the year. Thames Head they call it. There’s a stone there – like a gravestone in reverse, marking my birth. Once there was a grand statue there of Old Father Thames but this has been moved downriver, which feels more fitting, to St John’s Lock, near Lechlade, the highest point to which I am navigable. Beyond that, I remain a chaste maiden. No barges penetrate my leafy secrets. I am deflowered by commerce soon enough, but for a while I remain a virgin river – nay, a mere stream, like a strip of a girl, all knees and pigtails, awkward in her own body – before I become a womanly river. Appropriate, despite what I later become known as, for above where my cousin the River Thame joins me, a mere forty miles old (in Dorchester, Oxfordshire) I was known for centuries by gazetteers and cartographers as the Isis – a suitable name for an English Nile perhaps – an ancient name for the oldest stretch of me. Until half a million years ago this was my original course; then I flowed north-east to flow out into the sea at Ipswich. Well, when I say sea I mean the North Sea Basin. Then, I joined others to form the Channel River, among them the Rhine. But ice and flood made me change my ways. The great flood came, and the North Sea cut me off from my continental family tree.

And never the twain shall meet again.

Although dwarfed by my Egyptian sister and other siblings around the world, I am still the longest river in England (not quite Britain – that honour goes to big sis, Sabrina) and similarly prone to flooding. Indeed, some speculate the name the Celts gave me, Tamesas, means just this; the Darkly Flowing One. Was I once a Celtic goddess? They venerated water and believed rivers and springs were inhabited by spirits. Well, put Thame and Isis together and you have Thamesis, or eventually, Thames. And yet ‘Tamesis’ is a Greek girl’s name – for a goddess of the river.

I was rather fond of the Celts; they loved to offer me gifts: swords, knives, shields, coins, as well as their shining words. They gave me their prayers and blessings, wishes and curses. They fought to defend me – tattooed warriors; the thought of them gives me a thrill! Just saying their names brings a shiver to my spine: the Catuvellauni, the Atrebates, the Dobunni…

Then those tin men came, wanting to conquer it all. And many others followed: Vikings; Saxons; Normans. Fighting bloody battles by my banks; building castles to control me. All were conquered in the end by the land – settling down, raising crops and families. In the soft rain and mists of this island, their fierce blood cooled and they learned to love more than hate; to value life more than death.

Then came the trade – eel-trapping; willow-cutting; milling; fishing – and with it the traffic. Timber and wool, foodstuffs and livestock were carried on barges down from Oxford, as well as stone from the Cotswolds to rebuild St Paul’s after the Great Fire. Life got busy on the river – I became one of the busiest waterways in the world, one of the busiest ports, the hub of an Empire. I was the main artery of English life – ‘liquid history’ I have been called: history happened in, on and around me. English law was forged on one of my islands – Runnymede, where King John and the barons signed the Magna Carta in 1215. At Oxford the dreaming spires were raised and great minds were nurtured. Along my banks palaces fit for royalty were fashioned at Hampton Court, Kew, Richmond-on-Thames, Whitehall and Greenwich. The elite were weaned at Windsor and Eton. I carried kings and queens to their coronations at Westminster and executions at the Tower. Swans glided up and down me. Poets rhapsodised. Novelists took my dark water and turned it into ink; composers, into symphonies; artists, into light. All communed with my spirit, just as those Celts had done.

As, occasionally, the unsuspecting sightseer does.

The dancing patterns on the water are mesmerising, but beware! My beauty can be deadly, it can madden, and it can lead men to do insane things. It can lure them to their doom. And if I am not placated, if I am exploited, I can take a deadly toll. Many have been taken in my chill embrace. ‘Thames runs chill twixt mead and hill,’ it is said. How true.

On September 3rd 1878, I claimed my deadliest price, when the crowded pleasure boat

Princess Alice

collided with Bywell Castle, killing over 640 souls. In 1989, fifty-one party-goers drowned when the

Marchioness

was struck by a dredger. They were celebrating the birthday of a merchant banker; city-types; Thatcher’s children. Boom and bust, and down their ship of fools went.

Some say I have a cold heart. But by the time I have reached the capital I have been polluted, controlled, exploited and chartered. So, corrupted by the evil kings of this world, they hold me up as their own dark mirror and see an ancient patriarch. So perhaps you can forgive me if I turn bitter. Yet I have a bottomless heart. I embrace all who come to me – in the womb of death. Mother Thames. Your angel of mercy.

Come to me.

![]()

I based this story upon the recent sightings of the ‘Angel of the Thames’, an article by Robert Goodman, and my own research into the lore of the river. However sceptical one might be about such sightings, it is too tantalising for a storyteller to pass up. Although its source is in Gloucestershire and its estuary in Outer London, it is a prominent feature of Oxfordshire and I found it intriguing that it was often referred to as the Isis above Winchester-upon-Thames. It might seem far-fetched to conceive of a river ‘changing sex’, but since the British Celts saw the guardian spirits of the water as female (as in Sabrina of the Severn; and Sul of Aquae Sulis), it seems likely that ‘Tamesis’ was as well. Also, it has been noted that pollution in rivers can cause fish to change sex – it is perhaps using poetic license to extend this to the actual rivers themselves, but why not? Stranger things happen at sea.