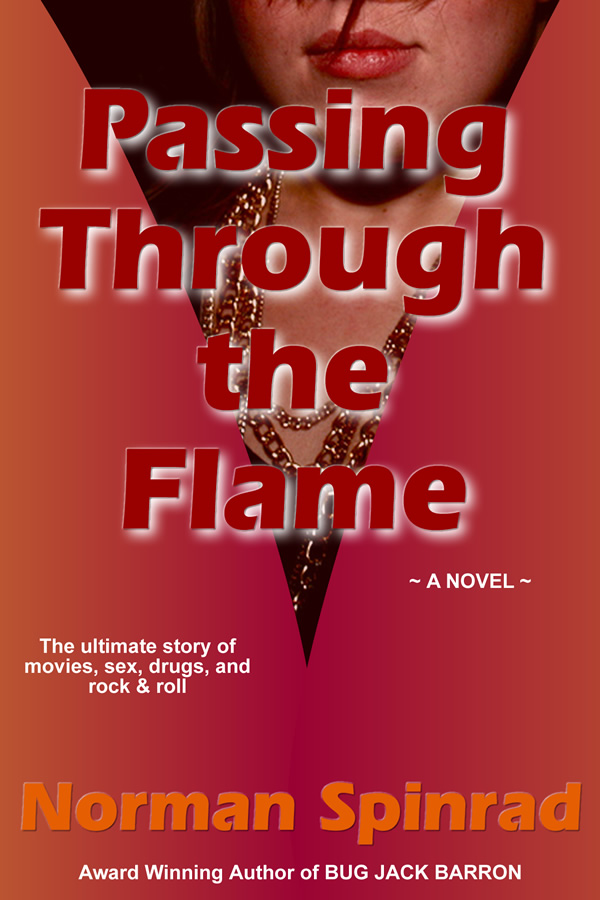

Passing Through the Flame

by

NORMAN SPINRAD

Published by

ReAnimus Press

Other books by Norman Spinrad:

Experiment Perilous: The 'Bug Jack Barron' Papers

The Last Hurrah of the Golden Horde

Staying Alive - A Writer's Guide

© 2012, 1975 by Norman Spinrad. All rights reserved.

http://ReAnimus.com/authors/normanspinrad

Licence Notes

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each person. If you're reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

AM I really hoping I can sell this piece of myself for thirty pieces of TV commercial silver? Paul Conrad wondered as he sat alone in the darkness watching the second reel of

Down Under the Ground

on his faded old movie screen.

A man in a brown leather jacket steps into a New York subway car. A murkiness of the film itself obscures his features, but it can’t hide his terror as he looks quickly up the car at an old woman in a frayed blue pea coat and yellow kerchief, entering through the next set of doors clutching a paper shopping bag filled with old newspapers.

Their eyes meet, and she appears on the screen from his point of view: a looming figure of menace towering above the blank and indrawn faces of the seated passengers, her face hidden by shadow.

Yeah, that low angle close-up makes it work, even underexposed, Paul thought. But the next shot, a close-up reaction shot of the man in the leather jacket, is so muddy as to be meaningless. Maybe I’m just running this to prove to myself that the technical quality isn’t there, that I can’t sell a piece of the only print to Harry Wilcox even if I want to, that two hundred dollars’ worth of temptation is no temptation at all.

The doors slide shut, and the train lurches into motion as the man in the leather jacket turns, almost stumbles, begins walking rapidly through the subway car against the forward motion of the train, straight into the eye of the camera. The camera begins to back through the car in front of him so that he seems to be forever rushing straight out of the screen as double lines of seated passengers, flickering fluorescent overhead lights, and colored advertising cards stream behind him like a comet’s tail.

Paul could hear the old projector grinding behind him, he could see the stain in the upper-right-hand corner of the screen and the Southern California sunshine edging the window shade, yet he found his own film overcoming all that, taking him back two years and three thousand miles to that other Paul who had made

Down Under the Ground

on a shoestring entirely within the New York subway system. Taking him beyond even that nostalgia and into the reality of the film itself....

The old woman in the pea coat follows the fleeing man, lurching ponderously in the swaying train like some inexorable natural force. She seems to blend into the ambience of the subway car as she waddles irresistibly toward the backing camera, stalking the man in the leather jacket. Old men in dark coats hang from the rows of handles above the seats like sides of meat. An unshaven man in a leather earlap cap wipes his nose with the back of his hand. Rubbish litters the blue-gray floor. An ashy black junkie nods on the long, green plastic bench seat. The old woman in the pea coat clutching her shopping bag seems a distillation of all this as she wallows up out of the miasma on the screen.

The man in the leather jacket reaches the end of the car, yanks open the heavy end door, staggers in the little space between the rolling cars, yanks the next door open, and dashes into the next car, almost running now, elbowing standing passengers aside.

The old woman follows—slowly, a bloated subaquatic behemoth swimming effortlessly through its natural element.

The running man jostles a young girl, who screams something at him as he pushes his way frantically through the crowded car into the next one.

The old woman in the frayed pea coat follows, patiently, through this car, then another, and another, and another.

The running man opens one more heavy door, and now he is in a nearly empty car. The light seems dim, gray, faded. A bearded old bum is sleeping on one of the bench seats, a bottle of port clutched to his breast. Across from him, a blind man with a tin cup sits with his Doberman guide dog. A fierce-looking black man in a white kaftan and turban drums beringed fingers loudly on the plastic surface of the seat beside him.

It is the last car in the train. Beyond the final door is only a black void spotted with streaming red, blue, and yellow lights. The floor of the car is strewn with old newspapers.

The man in the leather jacket pauses, looks around frantically, a trapped animal. Behind him the old woman enters the car, brandishing her bag of old newspapers like a club....

The train lurches, brakes squeal on iron, and we come to a grinding, rocking halt inside bustling Grand Central Station—platforms bursting with crowds and light and noise. The doors of the subway car slide open, and hordes of jostling, grunting people cram themselves inside as the man in the brown leather jacket fights his way out onto the subway platform, where he disappears into the human maelstrom—

White light filled the screen and the tag end of the film went snap! snap! snap! in the projector. Paul sat blinking for a moment, then turned off the projector, plunging the room into semidarkness.

Hopeless, he thought. Doesn’t even have the technical quality for TV commercial footage. I’d forgotten how really lousy the closeups were, and on a TV screen, the lack of proper contrast would turn even the long shots into mud. Fifteen thousand dollars and three weeks of my life, and I can’t even salvage two hundred bucks cannibalizing it for commercial footage.

The world’s best unreleasable film! Ninety-eight minutes of great footage shot in three crazy weeks on the cheapest color stock I could find with no time or money to develop daily rushes and find out I was blowing it. If I’d only been able to see rushes, I’d have seen that I simply couldn’t shoot color in the subways with the stock and equipment I could afford. I could’ve switched to black-and-white before it was too late, I could’ve.... Ah shit! Who would’ve distributed a black-and-white first feature anyway?

Paul went to the window, opened the shade, and bright Los Angeles sunlight flooded the little room. Outside, a Volkswagen bus embellished with crude psychedelic flowers drove slowly down the quiet Hollywood side street, past the rows of overgrown old apartment courts and the new pastel concrete motellike monstrosities that sprouted among them like overnight plastic toadstools. A line of dusty palm trees marched down the street.

This is California now, not New York two years ago, Paul thought.

Down Under the Ground

is a dead issue. I should never have tortured myself by looking at that footage again. He smiled ruefully, for he still couldn’t help admitting to himself that he was glad there was no temptation to cut up the only existing print of the film for a lousy two-hundred-dollar sale to a TV commercial producer. It could never be released, but the film was real, it was part of who he had been, which was part of who he was. It was art, goddamn it. His art.

To destroy the film, he felt, would be to deny the best part of himself and turn himself into just one more has-been or never-was Hollywood dreamer, grinding his life away on sleazy porn films, waiting for the Big Break that never came. Cannibalizing

Down Under the Ground

for two hundred dollars would be a kind of suicide, an admission of final defeat.

Paul opened the window, stuck his head out, and took a deep breath of smog. He suddenly felt a little light-headed, as if he were emerging from some Germanic funk.

What the hell, he thought, you never would’ve let yourself cut the thing up in the first place. Screw Harry Wilcox and his two hundred dollars! What’s two hundred dollars? Seven days’ work as a pornie cameraman.

Or this month’s rent and utilities. Which I’d better have by next Friday.

“We need some more footage, Velva. Want some K-Y?”

“I’m still wet, Larry, but will you move that damn spot? I can’t concentrate on balling when I’m going blind.”

Velva Leecock propped herself up on one elbow and took the towel from her makeup girl—who was also the script girl, who also went out for coffee and mainly was the regular ball of Larry Farber, the director. She wiped the sweat from her face, then toweled off her breasts. On color film, her pink nipples tended to lose definition against her creamy white skin unless they were firm and erect, and her costar just didn’t turn her on. A girl had to use every trick she knew in these low-budget skin flics; there was nobody around who really knew or cared about makeup and lighting. A tired old loser like Larry Farber could make Raquel Welch look like a sow. And it was important that every inch of film you appeared on show your body and face to best advantage, even if you were just balling some greaser on a water bed for the rent money. You never knew who might see you in what; the big break could come from anywhere.

Velva tossed away the towel and lay back on the water bed, her arms flung back and wide to lift her breasts, her long blond hair fanned across the red velvet pillow. She knew how sexy she looked, and she let the feel of her own body, the memory of her own naked mirror image, turn her on.

“Okay, lights...” Farber grunted tiredly.

A blinding white glare sent pins of pain through her eyeballs as that same damn spot came on, full in her face.

“Goddamnittohell, I told you to move that thing!” she screamed, sitting bolt upright and shielding her face with her forearm.

“Where the hell do you think you are, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer?” Farber bellowed. “We’re shooting a fuck film, not

Gone with the Wind

, and I need this angle. Maybe you’d care to direct too, as long as you’ve taken over the lighting.”

The cameraman, Paul she thought his name was, said, “Look, Larry, I could move back a little and off to the left, use a narrower lens, and then you could offset that spot enough so it wasn’t right in her eyes. Here, just let me....”

He loped over to the water bed and adjusted the light. He smiled briefly at her—wavy brown hair, smooth young face, hard gray eyes. “Okay, now lie back, see if that’s okay.”

She repositioned herself as before, looked up into the light. It was still hot, and there was still glare, but the thing wasn’t blinding her; it was the sort of thing a pro should be expected to cope with.

“Thanks,” she said, giving him a tiny smile.

“De nada,”

he said, returning to the camera and unscrewing the lens.

Larry Farber seemed annoyed that his cameraman had stepped in to fix things, but since he

had

fixed things, and since the shooting

was

way behind, and since Farber was a lame fourth-rater who had been making dull porn for ten years and would never do anything better, and knew it, he kept his mouth shut and let the young cameraman do his thing.

This Paul really does seem to know how to do his thing, Velva thought, I wonder how I’d feel doing his thing, she thought, giggling silently inside.

The cameraman finished changing lenses and gave Farber the high sign. “Okay,” Farber said with a sad little grimace, “Velva, you just move around and look hot. Conrad, I want about ninety seconds or so of this to use for cutaways. Don’t waste film. The budget is nonexistent, and we’re already over.”

“Listen, in New York, I shot dozens of shorts practically one for one,” Paul Conrad said.

“Wonderful, he’s a cost accountant too!” Farber groaned to empty air.

“I’m just telling you I know my job and then some, Larry,” Conrad said with a confidence in his voice that tickled something inside Velva. “I just want you to relax and feel comfortable.” The last, a definite zinger, obviously was meant to make Farber feel anything but comfortable. Paul Conrad, Velva thought, was better than Farber, and he knew it, and he wanted everyone else to know it. Velva decided he was a winner. He didn’t belong with all these porn creeps and old losers. He was on the way up. She felt the juices flowing.

“Now that we’ve all had our little ego trips, could we get these lousy ninety seconds of film?” Farber said. “Velva, move your ass! Conrad, exercise your precious talent!”

Velva began gyrating her lower torso, rotating her body from the rib cage down, billowing the loose surface of the water bed in rhythmic waves under her hips and lower back. She stared straight into the glass eye of the camera as she made love to the empty air, picturing Paul Conrad’s eye on the other side of the viewfinder, playing to that eye; the eye of both the eventual viewer of the film and of the only man in the studio whom she cared to turn on.