Read Paul Revere's Ride Online

Authors: David Hackett Fischer

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #United States, #Historical, #Revolutionary Period (1775-1800), #Art, #Painting, #Techniques

Paul Revere's Ride (30 page)

The great fear was great because it was so general and all-encompassing. It became a broad undifferentiated emotion, feeding on anxieties that had nothing to do with the immediate cause. In the town of Framingham, ten miles southwest of Concord, a local inhabitant remembered that “soon after the men were gone, a strange panic seized the women and children living in the Edgell and Belknap district. Someone started the story that ‘the negroes were coming to massacre them all!’” An historian of that town remembered that “nobody stopped to ask where the hostile negroes were coming from; for all our own colored people were patriots. It was probably a lingering memory of the earlier Indian alarms, which took this indefinite shape, aided by a feeling of terror awakened by their defenceless condition, and the uncertainty of the issue of the pending fight.”

15

Here was another parallel between this American great fear

and the

grande peur

in France in 1789. The same range of apprehensions appeared in different forms: French peasants worried about “brigands,” while Americans feared the rising of their slaves.

In both countries, strangers became suspect. The women of Framingham prepared to defend themselves against they knew not what. One townsman remembered that “the wife of Capt. Edgell and other matrons brought the axes and pitchforks and clubs into the house, and securely bolted the doors, and passed the day and night in anxious suspense.” Many accounts stress the effect of “anxious suspense” on the nerves of noncombatants. A large part of the great fear arose from uncertainty.

16

But others were clear enough about what should be done. A case in point was the town of Pepperell, twenty miles northwest of Concord. When the men of Pepperell marched away the women came together and held their own town meeting. They organized themselves into a military company, and elected as their captain Prudence Cummings Wright, wife of a leading townsman, and mother of seven children. “Prue” Wright, as she was called, was a deeply religious woman who had joined the Congregational church in 1770. Her family was divided in politics. Her brothers were active Tories, but she and her husband were staunch Whigs. They christened their infant son Liberty Wright.

Young Liberty Wright died in March 1775, and their daughter Mary had been buried only nine months earlier—a loss so heavy that Prudence Wright left her own household for a time and went home to her parents in New Hampshire. But by April 19, 1775, she was back again, and the women of Pepperell elected her to lead them. She appointed Mrs. Job Shattuck as her lieutenant, and organized the women into a company called “Mrs. David Wright’s Guard,” They dressed themselves in their husbands’ clothing, armed themselves with guns and pitchforks, and began to patrol the roads into the town.

These women of Pepperell kept patrolling even after dark. They were guarding a bridge that night, when a rider suddenly approached. The women stopped him at gunpoint and forced him to dismount. He proved to be a Tory named Captain Leonard Whiting. They searched him, found incriminating papers, marched him under guard to Solomon Rodger’s tavern in the town center and kept him a prisoner that night. The next morning he was sent to Groton, and his papers were dispatched to the Committee of Safety for study. The Pepperell town meeting later

reimbursed Mrs. Wright and the women of her company for their service. With a hint of condescension, the men voted “that Leonard Whiting’s guard (so called) be paid seven pounds seventeen shillings and six pence by order of the Treasurer.” But on the night of April 19, there was nothing of that attitude in Captain Leonard Whiting, when Prue Wright stopped him at gunpoint and threatened to kill him if he did not obey.

17

Tories were arrested in many New England towns. At Scituate on the South Shore of Massachusetts, Paul Litchfield noted in his diary that “very early in the morning of April 20, the town “received news of the engagement between the king’s troops and the Americans at Concord the day before, upon which our men were ordered to appear in arms immediately.” Litchfield was sent to guard the coast, in fear of British attack from the sea, a feeling that was shared in many coastal communities. His company “about eight o’clock took two Tories as they were returning from Marsh-field, who were kept under guard that night.” The next day they arrested four Tories more, and confined them in the meetinghouse.

The great fear continued for many days throughout New England. “Terrible news from Lexington, … rumor on rumor,” John Tudor entered into his diary, “men and horses driving past, up and down the roads. … People were in great perplexity; women in distress for their husbands and friends who had marched. … All confusion, numbers of carts, etc. carrying off goods etc. as the rumour was that if the soldiers came out again they would burn, kill and destroy all as they marched.”

18

On the North Shore of Massachusetts, there was a special panic called the “Ipswich fright.” A report spread through Essex County that British soldiers had come ashore in the Ipswich River and were murdering the population of that town. The rumor traveled at lightning speed up and down the coast. It was written that “all the horses and vehicles in the town were put in requisition: men, women, and children hurried as for life toward the north. Large numbers crossed the Merrimack, and spent the night in deserted houses of Salisbury, whose inhabitants, stricken by the strange terror, had fled into New Hampshire.”

19

The panic infected Salem, where John Jenks recorded in his diary on April 21,1775, “A report was propagated that Troops was landed in Ipswich.” Jenks heard the next day that “the report was false, no troops came there.” But he and his fellow townsmen decided

to take no chances. On the 23rd of April he wrote, “moved my goods up to my Uncle Preston in Danvers. A great number of teams was employed to carry provisions out of the town.”

20

In Newbury, a messenger appeared at an emergency town meeting, crying, “Turn out, for God’s sake, or you will all be killed. The Regulars are marching on us; they are in Ipswich now, cutting and slashing all before them.”

21

In the interior town of Haverhill, the Reverend Hezekiah Smith, pastor of the Baptist Church wrote in his diary, “a most gloomy time. … Repeated false alarms, and terrifying apprehensions.” He held a day of fasting and prayer in his meetinghouse, as did many other ministers throughout New England.

22

The same emotions spread to the interior of Massachusetts. They were felt at Sudbury, twenty miles inland, where Experience Wight Richardson kept a diary that was running record of her anxiety. She feared not for herself but for others: for her only son Josiah Richardson who went off to “fite” and for other men and families in her town. In particular, she feared for the people of Boston. “We are afraid that Boston people a great many will starve to death,” she wrote. “O Lord! Appear for them I pray thee. O King Jesus help us I pray thee.”

23

The great fear reached as far as the town of Sutton, forty miles from the coast, and persisted there for many days. After April 19, the town’s minister David Hall wrote, “That night there was several alarms. I was up most of the night and prayed with our minute companies a little before day.” He comforted his congregation for many days. “A dark and melancholy week we had,” he noted in his diary.

24

The great fear also spread to Loyalists in Boston and even to the Regulars themselves. Admiral Samuel Graves later remembered that a wave of hysteria swept through the British troops, who were suddenly conscious that they were in “the neighbourhood of so enraged an host of people, breathing revenge for their slaughtered countrymen, and vowing to storm Boston, seize upon and demolish Castle William, fortify Point Alderton, burn all the men of war, and cut off every Tory.” Graves recalled that “each of these reports through the fears of some and wickedness of others was industriously circulated, during the first week or two after the battle of Lexington, and some of them gained credit … such rumors spread abroad, could not but excite on our part the utmost attention.”

25

Among the American leaders, the great fear gave them yet

another task. At the same time that they worked to raise the alarm in Massachusetts, they also labored to quiet the anxieties of the people. The network of couriers continued to function for many days, keeping the towns informed about the course of events, but without laying their fears to rest. It was typical of this Calvinist culture that people interpreted this time of suffering as a divine judgment on their own depravity. For many Sundays afterward, the ministers of Massachusetts preached from the first verse of Lamentations: “The joy of our heart is ceased; our dance is turned into mourning. The crown is fallen from our head; woe unto us, that we have sinned.”

26

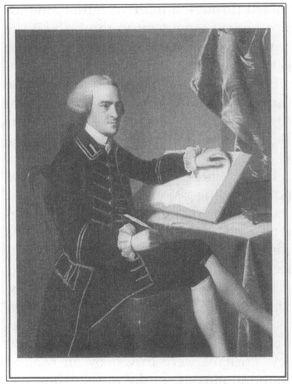

Of John Hancock, Sam Adams, a Salmon, and a Trunk

Of John Hancock, Sam Adams, a Salmon, and a Trunk

It is supposed their object there was to seize on Messrs. Hancock and Adams, two of our deputies to the General Congress. They were alarmed just in time to escape.

—Letter from a Gentleman of Rank in New England, April 25, 1775

W

HILE THE COUNTRYSIDE

began to stir, the man who had set these events in motion hobbled back toward Lexington, painfully encumbered by his silver spurs and heavy riding boots. It was about 3 o’clock in the morning when Paul Revere regained his freedom. The night had turned cold and raw and darker than before—the damp Stygian darkness that so often comes before a New England dawn.

As Paul Revere passed the low swamps that lay west of Lexington Green, he would have felt the dampness in his weary bones. He made slow progress in his high-topped boots on the muddy road, but his mind was racing far ahead. He wondered what Samuel Adams and John Hancock had done since he left them. Had they ended their interminable debate? Were they still debating? Did they act wisely on their warning?

Knowing Hancock and Adams, Paul Revere decided that he had better be sure. Before he reached the center of the town, he turned off the road, plunged into a muddy swamp, and waded across the wetlands to Lexington’s burying ground. In the darkness, he picked his way across the broken slates and canted stones that marked the last resting place of the town’s founders.

As Paul Revere stumbled through a maze of burial mounds and sunken holes, perhaps he had a moment to think about the men and women whose mortal remains lay beneath him in the ground. Inconceivable as it may seem to their degenerate descendants, the Whig leaders of revolutionary America often had these periods of reflection. They took a long view of their temporal condition, in a way that Americans rarely do today. “Think of your forefathers!” John Quincy Adams urged his contemporaries, “Think of your posterity!”

Paul Revere and his fellow Whigs believed themselves to be the heirs of New England’s founding vision, and the stewards of John Winthrop’s City on a Hill. The moral example of their forebears haunted and inspired them. When Sam Adams signed his revolutionary writings with the pen-name “Puritan,” and Paul Revere created his political engravings on godly themes, they expressed their strong sense of spiritual kinship with their ancestors.

For these men, the revolutionary movement was itself a new Puritanism—not precisely the same as the old, but similar in its long memories and large purposes. Like the old Puritans who had preceded them, these new Puritans were driven by an exalted sense of mission and high moral purpose in the world. They also believed that they were doing God’s work in the world, and that no earthly force could overcome them. In the language of the first Puritans, they were both believers and seekers—absolutely certain of the rightness of their cause, and always searching restlessly for ways to serve it better. In that endless quest, the memory of distant ancestors who lay sleeping in the grave was a source of guidance and inspiration to them.

At the same time, they also thought of their posterity. These men were deeply conscious of their own mortality—more than we are apt to be today. They looked ahead to the time when they too would be lying beneath the broken slates of New England’s burying grounds, and asked themselves if their acts would be worthy of generations yet unborn. Perhaps some of these thoughts (which have so little meaning to Americans today) may have occurred to Paul Revere, as he felt his way through the broken stones of Lexington’s burying ground during the dark hours before the dawn of April 19, 1775.

At last Paul Revere emerged from the burying ground and turned north to the Bedford Road. He walked a few hundred yards to the Clarke parsonage, hoping to find that the men he had come from Boston to warn were safely away. As he entered the door, Paul Revere was horrified to find that Sam Adams and John Hancock were precisely where he had met them three hours ago— still debating among themselves.