Read Paul Revere's Ride Online

Authors: David Hackett Fischer

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #United States, #Historical, #Revolutionary Period (1775-1800), #Art, #Painting, #Techniques

Paul Revere's Ride (34 page)

Some thought that the first shot came from Major Pitcairn himself. One swore that he “heard the British commander cry,

‘Fire!’ and fired his own pistol and the other officers soon fired.” Pitcairn, an honorable man, absolutely denied that he did any such thing, and insisted that he told his troops

not

to fire. His brother officers strongly supported him. Lieutenant Sutherland wrote, “I heard Major Pitcairn’s voice call out, ‘Soldiers, don’t fire, keep your ranks, and surround them.’”

35

Other Americans believed that the first shot came from another British officer. Thomas Fessenden testified that as Pitcairn rode to the front, a second officer “about two rods behind him, fired a pistol.” The minister Jonas Clarke also thought that “the second of these officers fired a pistol towards the militia as they were dispersing.” It might have been the excitable Major Mitchell, or possibly Lieutenant Sutherland, an aggressive young volunteer who was armed with a pistol and mounted on a fractious horse that he could not control.

36

What probably happened was this: several shots were fired close together—one by a mounted British officer, and another by an American spectator. Men on both sides were sure that they heard more than one weapon go off; men on each side were watching only their opponents. If there were several shots at about the same time then all spoke the truth as they saw it, but few were able to see the entire field.

37

It is possible that one of these first shots was fired deliberately, either from an emotion of the moment, or a cold-blooded intention to create a incident. More likely, there was an accident. Firearms seemed to have a mind of their own in the 18th century. Only a few years earlier, such an accident had happened at a military review of the 71st Foot in Edinburgh, “some of the men’s pieces going off as they were presented.” Many weapons at Lexington, both British and American, were worn and defective. An accident might well have occurred on either side. If so, it was an accident that had been waiting to happen.

38

We shall never know who fired first at Lexington, or why. But everyone on the Common saw what happened next. The British infantry heard the shots, and began to fire without orders. Their officers could not control them. Lieut. John Barker of the 4th Foot testified that “our men without any orders rushed in upon them, fired, and put ‘em to flight.” Major Pitcairn reported that “without any order or regularity, the light infantry began a scattered fire.”

The British firing made at first a slow irregular popping sound, which expanded into a sharp crackle. Then suddenly there

was a terrible ripping noise like the tearing of a sheet, as the British soldiers fired their first volley. That cruel sound was followed by what Paul Revere described as a “continual roar of musketry” along the British line.

Things were moving very quickly, but to the New England men who received this fire only a few yards away, events seemed to be happening in slow motion. Lexington militiaman Elijah Sanderson saw the Regulars shoot at him, but he was amazed that nobody seemed to fall, and thought that the Redcoats were firing blanks. Then one British soldier turned and fired toward a man behind a wall. “I saw the wall smoke with the bullets hitting it, Sanderson recalled, “I then knew they were firing balls.”

John Munroe also believed that the Regulars were firing only powder, and said so to his kinsman Ebenezer Munroe who stood beside him. But on the second fire Ebenezer said that “they had fired something more than powder, for he had received a wound in his arm.” He added, “I’ll give them the guts of my gun,” and fired back.

39

The two lines, British and American, were very close—about sixty or seventy yards apart, John Robbins remembered. Others thought them even closer. Sanderson was amazed that the Regulars “did not take sight,” but “loaded again as soon as possible.” The British infantry were doing automatically what they had been taught. There was no command for “take aim” in the British manual of arms in 1775, only “present.” The men were firing, reloading, presenting, and firing again with the incredible speed that made the British infantryman and his Brown Bess so formidable on a field of battle. One of the officers wrote that the firing “was continued by our troops as long as any of the Provincials were to be seen.”

40

With the crash of musketry, one of the British officers, Lieutenant Sutherland, lost control of his captured horse. The frightened animal bolted forward, straight through the New England militia to the far end of the Green. Sutherland managed to turn his terrified horse and galloped back again, as the militia and spectators scurried out of his way. Two New England men, Benjamin Tidd of Lexington and Joseph Abbott of Lincoln, were also looking on from horseback. After the volley from the Regulars they testified, “Our horses immediately started, and we rode off,” not of their own volition.

The spectators fled for their lives. Timothy Smith of Lexington testified that after the Regulars fired, “I immediately ran,

and a volley was discharged at me, which put me in imminent danger. Thomas Fessenden, watching from near the meetinghouse, said, “I ran off as fast as I could.”

41

Heavy lead musket balls flew in all directions, making a low whizzing noise which sounded to some like a swarm of bees. Paul Revere, still struggling with John Hancock’s trunk, found himself directly in the line of fire, about “half a gunshot” from the British troops. He later remembered that the balls were “flying thick around him.” Revere and Lowell stayed bravely with the trunk as the British rounds passed close above their heads. They carried their precious burden into the woods beyond the Common, and remained there for about fifteen minutes.

42

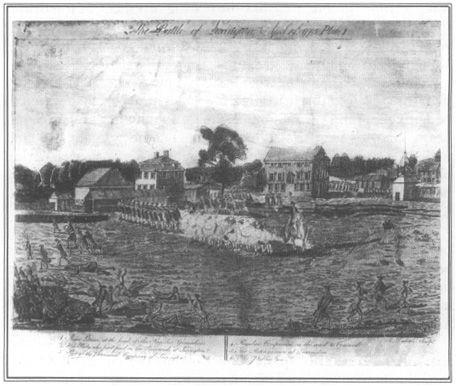

Ralph Earl’s sketch of the fight at Lexington Green was made shortly after the battle, on the basis of interviews with eyewitnesses. It is an important piece of evidence, very accurate in its location of British and American units, and in its rendering the Common itself. (New York Public Library)

The Common was shrouded in dense clouds of dirty white smoke. One militiaman remembered, “All was smoke when the Foot fired.” Another recalled that “the smoke prevented our seeing anything but the heads of some of their horses.” The British

infantry fired several ragged volleys, then charged forward without orders through the smoke, lunging with their long bayonets at anyone they found in their way.

43

A few American militia managed to get off a shot or two. The youngsters ran, but several of the older men were determined to fight back. Many remembered seeing Captain John Parker’s kinsman Jonas Parker “standing in the ranks, with his balls and flints in his hat, on the ground between his feet, and heard him declare, he would never run. He was shot down at the second fire… I saw him struggling on the ground, attempting to load his gun… As he lay on the ground, they run him through with the bayonet.”

44

John Munroe also fired back. “After I had fired the first time, I retreated about ten rods, and then loaded my gun a second time, with two balls… the strength of the charge took off about a foot of my gun barrel.” Ebenezer Munroe stood and fought too. He wrote later, “The balls flew so thick, I thought there was no chance for escape, and that I might as well fire my gun as stand still and do nothing.” He remembered trying to take aim, but the smoke kept him from seeing the Regulars, and he did not hear Captain Parker’s orders to disperse.

45

Most of the American militiamen did not return fire. Their minister Jonas Clarke wrote that “far from firing first upon the King’s troops; upon the most careful enquiry, it appears that but very few of our people fired at all.”

46

The British infantry suffered only one man wounded, Private Johnson of the 10th Foot, shot in the thigh. Major Pitcairn’s horse was hit in two places, and Pitcairn himself was later seen nursing a bloody finger in Concord.

47

On the other side, the toll was heavy. Two militiamen (only two) fell dead on the line where they had mustered—Jonas Parker and Robert Munroe. The rest were killed while trying to disperse, as they had been ordered. Jonathan Harrington was mortally wounded only a few yards from his home on the west side of the Common. His wife and son watched in horror as he fell in front of the house, and struggled to get up again, his life’s blood coursing from a gaping chest wound. Jonathan Harrington rose to his knees and stretched out his hands to his family. Then he fell to the ground and crawled painfully toward his home, inch after inch, across the rough ground of the common. He died on his own doorstep.

Samuel Hadley and John Brown were also shot while running from the Common. Hadley’s body was found near the edge of a nearby swamp. Asahel Porter, the Woburn man who had been

taken prisoner, tried to run and was killed a few rods beyond the Common.

48

Four Lexington militiamen were in the meetinghouse, which was also the town’s powder magazine. They came out just as the shooting started. One of them, Caleb Harrington, was killed as he tried to flee. Another, Joseph Comee, was wounded in the arm as he ran for cover. A third, Joshua Simonds, ducked back into the meetinghouse with British soldiers in pursuit. He raced to the upper loft where the munitions were kept, sank to the floor, and thrust his loaded musket into a powder barrel, determined to explode the entire magazine if the Regulars entered. British soldiers moved toward the building; several began to enter it. Joshua Simonds heard their footsteps on the stair, and prepared to blow up the powder.

49

At that moment Colonel Francis Smith suddenly arrived on the field, with the main body of his force. Smith was horrified by the scene that greeted him. The bodies of wounded and dead militiamen were scattered about the bloody ground. The British infantry, famous for their discipline in battle, were running wildly out of control. Their officers appeared helpless to restrain them. Small groups of Regulars were firing in different directions. Some were advancing on private houses. Others were moving toward the Buckman Tavern. A few were inside the meetinghouse, and preparing to assault the upper story where Joshua Simonds awaited them, with his musket plunged into a powder barrel and his finger on the trigger.

Tavernkeeper William Munroe was Lexington’s orderly sergeant, who told Paul Revere not to make so much noise, as people were trying to sleep. Afterward he helped Adams and Hancock find a place of safety, and returned in time to muster with Captain Parker on Lexington Common. This portrait was painted by Ethan Allen Greenwood in 1813, when Munroe was seventy-one. (Lexington Historical Society)

Unlike his green junior officers, Colonel Smith knew from long experience exactly what to do. He rode straight into the center of the scene, met Lieutenant Sutherland, and asked, “Do you know where a drummer is?” A drummer was quickly found, and ordered to beat to arms. The throb of the drum began to reverberate across the Common. The Regulars had been trained in countless drills to respond automatically to its commands. The British infantry heard the drum’s call, steady and insistent even above the rattle of musketry. Reluctantly, the men ceased firing and turned toward their angry commander.

50

Smith ordered them to form up. Some of the men responded sullenly. Others did not respond at all. One officer remembered “We then formed on the Common but the men were so wild they could hear no orders.” Another wrote, “We then formed on the Common, but with some difficulty.” Slowly the companies came together, and sergeants prodded the men into ranks.

51