Read Paul Revere's Ride Online

Authors: David Hackett Fischer

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #United States, #Historical, #Revolutionary Period (1775-1800), #Art, #Painting, #Techniques

Paul Revere's Ride (37 page)

The senior British officer at the bridge was Captain Walter Laurie. With him were three light infantry companies from the

4th, 10th and his own 43rd Foot, about 115 men in all.

34

Laurie watched the New Englanders advance, and ordered his three companies to form for “street firing” behind the bridge. This was a typically complex 18th-century maneuver, designed to dominate a small space with overwhelming firepower. In one version, each company was ordered to form in narrow ranks, one rank behind the other. The men were trained to “lock” their formation—the front rank kneeling, the second rank shifting half a step to one side, and the third rank moving in the opposite direction, so that three ranks could present their muskets and fire simultaneously. After firing, the front ranks filed quickly to the rear and formed up again. They reloaded while the next ranks stepped forward and fired in their turn. The object was to present continuous volleys of musketry in a constricted area.

35

“The White Cockade” was a lively Jacobite tune that enjoyed wide popularity in 1775. It was played by Acton’s fifer Luther Blanchard and drummer Francis Barker on the field at Concord’s North Bridge. This rustic version was set down a few years later by a Yankee musician. It is in the collections of the New Haven Colony Historical Society.

The Americans beyond the west bank of the river were in a different formation. They came forward in double file, holding their muskets at the trail in their left hands. The line of their long formation curved down the hill to the southwest, then turned eastward and followed a causeway that ran eastward beside the river to the bridge.

36

As the New England militia approached, the British soldiers on the other side of the river struggled to form up in their street-firing formation behind the bridge. They were caught in a tangle of confusion. Two companies had hurried back across the bridge and collided with a third. All became intermingled in a milling crowd. In the rear, Lieutenant Sutherland of the 38th ordered the light infantry of the 43rd to move out as flankers onto a field to the south of the road. But he was not their commander, and only three men obeyed him.

37

Suddenly a shot rang out. Captain Laurie saw with horror that one of his own Regulars had fired without orders. Then two other British soldiers fired before he could stop them, and the front rank of the British troops discharged a ragged volley with the same indiscipline that they had shown at Lexington.

38

The inexperienced British infantry fired high, as green troops tend to do. Most of their volley passed harmlessly over the heads of the militia. Thaddeus Blood remembered that “their balls whistled well.”

39

But several shots hit home. Acton’s quiet Captain Isaac Davis was killed instantly by a ball that pierced his heart; the arterial blood spurted from his wound, and drenched the men beside him. Private Abner Hosmer of the same company fell dead, shot through the head. Fifer Luther Blanchard was wounded, and three others were hit. A man from Lincoln received a strange narrow cut from a grazing shot, and wondered aloud if the British were “firing jack knives.” Nearly all of the wounds were to the head and upper body.

40

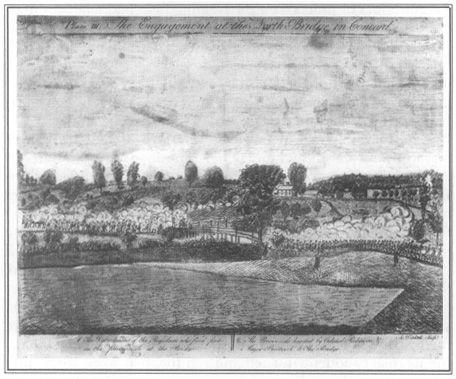

Ralph Earl’s sketch of the engagement at Concord Bridge was crude in its drawing but careful of its facts. Earl worked from interviews of survivors, and he represented accurately the positions of British and American troops at the first fire. His drawing also gives a good sense of the open terrain in 1775. The house in the distance (turned slightly on its axis) belonged to Major John Buttrick, who led the American advance on his own land. The field in the foreground was next to William Emerson’s Old Manse. (New York Public Library)

Still the Americans came on steadily, with a discipline that astonished their enemies. They were now very close, fifty yards from the bridge, well within the killing range of 18th-century muskets.

41

As men began to fall around him, Major Buttrick of Concord turned and cried, “Fire, fellow soldiers, for God’s sake fire!” The men themselves took up the command. Private Blood remembered that “the cry of fire, fire was made from front to rear. The fire was almost simultaneous with the cry.”

42

The New England muskets rang out with deadly accuracy.

Recent hours of practice on the training field had made a difference. The Americans aimed carefully and fired low. Many appear to have drawn a bead on the British officers, whose brilliant scarlet uniforms stood out among the faded coats of their men. Two months later at Bunker Hill the best American marksmen were ordered “to fire at none but the reddest coats.” Something similar happened at Concord. Of eight British officers at the North Bridge, four were hit in the first American fire. At least three privates were killed, and altogether nine men were wounded.

43

The Regulars found themselves caught in a trap. The New England minutemen and militia were deployed in two long files curving down the hill and along the causeway. Many men in that formation had a clear shot. The British soldiers were packed in a deep churning mass; only the front ranks could fire. The loss of officers compounded the confusion. As the firing continued, dense clouds of white smoke rose on both sides of the river.

44

The New England men peered through the fog of battle, and saw a strange shudder pass through the smoke-shrouded ranks of the British soldiers. Then, to the amazement of American militia, the Regulars suddenly turned and ran for their lives. It was rare spectacle in military history. A picked force of British infantry, famed for its indomitable courage on many a field of battle, was broken by a band of American militia. British Ensign Lister wrote candidly, “The weight of their fire was such that we was obliged to give way, then run with the greatest precipitance.”

45

The British light infantry fled pell-mell back toward Concord center, defying their officers and abandoning their wounded, who were left to drag themselves painfully away. The American militia watched, less in exhilaration than in what seems to have been a kind of shock, as the Regulars disappeared in the distance, followed by wounded men “hobbling and a’running and looking back to see if we was after them.”

The New England formation was also disrupted by its own success. It had no idea what to do with its victory. This was the moment when one soldier, Thaddeus Blood, remembered that “after the fire every one appeared to be his own commander.”

46

Some advanced; others retreated. Order and discipline disintegrated. A few of the Yankee militia had seen enough of soldiering, and departed for the day. The wife of Captain Nathan Barrett saw one of these men walking away from the bridge. She “called to him and enquired of him where he was a going. He says I am a going home. I am very sick. She says to him, you must not take your gun

with you. Yes, he says, I shall. No, stop, I must have it. But no, so off he went upon the run, and she after him, but he got away and she gave up the chase.”

47

The American dead were taken to the house of Major Buttrick near the muster field, where Captain Isaac Davis was laid out in the parlor. Colonel Barrett sent the wounded to his own home, to be looked after by his wife. As that lady was dressing a flesh wound she said, “Poor man, and a little more and you would have been in eternity.” He answered sharply, “Yes, damn it, and a little more and the ball would not have touched me.” When the bandage was complete, he returned to his company.

48

As the British soldiers fled toward the village, a solitary American entered the road near the bridge, carrying a hatchet in his hand. He came upon a severely wounded Regular on the ground before him. The American raised his hatchet and brought it down on the head of the helpless soldier, crushing his skull and exposing his brains, but not killing him.

49

Meanwhile in Concord center, Colonel Smith had been overseeing the search of the houses by his Regulars when a message arrived from Captain Laurie at the North Bridge, asking urgently for reinforcements. Suddenly Smith heard the crash of heavy firing. His experienced ear told him that this was no mere skirmish. He mustered two companies of grenadiers and led them himself toward the sound of the guns. On the road to the bridge, they met the broken remnants of the light infantry, retreating in disorder. Smith, marching at the head of the grenadiers, knew that four of his companies were still beyond the bridge at Colonel Barrett’s house. The British commander was concerned to hold open their line of retreat.

The New England officers began to recover control of their scattered men—no small achievement with green militia after a battle. Colonel Barrett took a chance and divided his force. He held the older men of the militia and the alarm lists on the west side of the river, and sent them to their muster field. Buttrick’s minutemen crossed the North Bridge, advanced a short distance toward Concord center, and took up a strong defensive position on a hill behind a stone wall. One of the men with Buttrick, Concord minuteman Amos Barrett, wrote later in his Yankee dialect, “We then saw the hull body acoming out of town we then was orded to lay behind a wall that run over a hill and when they got ny anuff mager buttrick said he would give the word fire but they did not come quite so near as he expected before tha halted. The

commanding officers ordered the hull battalion to halt and officers to the frunt march and the officers then marched to the front thair we lay behind the wall about 200 of us with our guns cocked exspecting every minnit to have the word fire. Our orders was if we fired to fire 2 or 3 times and then retreat.”

50

The grenadiers saw the minutemen behind their wall on high ground, and halted while still out of range 200 yards away. The British officers came to the front, and studied the American force with a new respect. Amos Barrett wrote later, “If we had fird I be leave we could kild all most every officseer thair was in the front, but we had no orders to fire and their want a gun fird.”

51

Colonel Smith observed the strength of the American position, and the steadiness of the quiet men who held it. He wisely ordered the Grenadiers to fall back. “They stayed about 10 minutes and then marched back,” Blood remembered.

52

While the two forces confronted one another, a strangely surrealist scene ensued. A madman wandered unmolested through the center of the action. He was Elias Brown of Concord, a “crazy man” his minister called him. He had long been allowed to move freely in the town, doing odd jobs for his neighbors. That day he had been happily pouring hard cider for men on both sides. His Concord cider had fermented all winter and was twenty proof by April; Elias Brown did a brisk business that day. When the fighting began at the North Bridge he went among his New England townsmen and said that he “wondered what they killed them [the Regulars] for. They were the prettiest men he had ever seen and kept him drawing cider all the time.” For a moment this “crazy man” may have been the sanest person in town.

53

At last the four British companies came hurrying back from Colonel Barrett’s mill on the far side of the North Bridge. When they saw what had happened, they began to run toward the bridge, in fear of being cut off. Their route took them directly under the muskets of Barrett’s militia west of the river, and Buttrick’s minutemen on the east side. To the surprise of the British officers, the New England men held their fire, still reluctant in this twilight zone between peace and war to attack the King’s troops without cause. The British infantry were suddenly very careful not to provoke these dangerous and unpredictable men.

The four companies of light infantry crossed over the North Bridge and turned toward Concord. In the road they came upon the dying Regular who had been brained with an American hatchet, and appeared to have been scalped as well. Instantly the word spread among the Regulars that the Americans were murdering prisoners and torturing the wounded. The story flew from mouth to mouth, growing as it traveled. By the time it reached Ensign Lister he was told that “four men of the Fourth company [had been] killed and afterwards scalped, their eyes gouged, their noses and ears cut off.”

54