Read Pearl Harbor Christmas Online

Authors: Stanley Weintraub

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #United States, #20th Century

Pearl Harbor Christmas (10 page)

CHRISTMAS EVE IN THE PHILIPPINES, to the southeast and an hour before Tokyo time, came more than half a day earlier than in the United States, across the International Date Line. The nearly unopposed Japanese landing at Lamon Bay, southeast of Manila, that morning had left the capital defenseless from every direction. Based on MacArthur’s communiqués, largely fiction, the

New York Times

headlined, “OUR TANKS AND ARTILLERY POUND INVADERS.” Landing at Lingayen Gulf and quickly moving south, General Homma set up his headquarters north of San Fernando, above Manila Bay. Not far below, defenders were protecting the Calumpit Bridges, over which they funneled retreating troops, and failed to prevent refugees from fleeing, into the Bataan Peninsula, a two hundred–square mile thumb of hills and jungle thrusting south into Manila Bay. Much of Luzon’s stored food supplies for defending troops were now beyond reach. Major General Jonathan Wainwright put soldiers on two-thirds rations. His forces were already backing into Bataan where, according to MacArthur’s Plan Orange 3, they were to hold on for six months until relief would come from the American mainland. But by every measure Orange had become instantly obsolete on the first day of the war. His radioed proposal that such fleet units from Hawaii as were left should risk an attack on the Japanese Home Islands in order to draw enemy strength away from the Southwest Pacific was considered fantasy by Washington, as was his proposal that the only two big carriers in the Pacific could fly aircraft to the Philippines.

That afternoon MacArthur’s deputy, Brigadier General Richard Sutherland, summoned key officers to headquarters in Intramuros to inform them that they would be leaving Manila for Corregidor at dusk. MacArthur took a last glance at his flag-bedecked office and asked Sergeant Paul Rogers to “cut off” the red banner with the four white stars of a full general which flew from the limousine he would have to abandon. Rogers untied the thongs from the post and rolled up the flag. MacArthur thanked him, tucked it under his arm, and crossed palm-lined Dewey (now Roxas) Boulevard to the Manila Hotel.

Each staff member would be permitted field equipment and one suitcase or bedroll. Jean MacArthur again unwrapped her presents and filled her suitcase (labeled New Grand Hotel, Yokohama) and that of her son and his

amah,

Ah Cheu, with clothes, canned food, her jewelry, some family pictures, her husband’s medals wrapped in a towel monogrammed Manila Hotel, and his gold Philippines army field marshal’s baton. Sid Huff carried Arthur’s new tricycle, and Ah Cheu his stuffed rabbit, Old Friend. Before departing Intramuros, MacArthur had sent for Japanese Consul-General Nihro Katsumi, then in mild detention, to ask him to confirm to the Japanese command that defenseless Manila was to be declared an Open City.

“Ready to go to Corregidor, Arthur?” Jean MacArthur asked the bewildered boy. He nodded and took Ah Cheu’s hand as she opened the door to the wail of air-raid sirens. The MacArthurs, with Huff, left for the Cavite docks in the general’s black Packard. The extensive military history library, and everything else in the flat, would be at the pleasure of General Homma.

At 7:00 P.M. the interisland steamer

Don Esteban

weighed anchor for Corregidor with the MacArthur party aboard. After dark it was still a warm eighty degrees, and some of those who had gone below crowded onto the forward deck for the breezes stirred by the passage. In the quiet of evening, with enemy aircraft gone and the glow of the fires on the Cavite docks receding, a few, unwilling to miss Christmas altogether, began singing “Silent Night”—and others joined in with further carols until they felt too depressed to continue. (Biographer William Manchester wrote, rather, that no one joined a lone caroler.) There was nothing to encourage evacuees to believe that Corregidor and Bataan could hold out until rescue. The huge, squat mortars which were the Rock’s most formidable defensive weapons were embossed “Bethlehem Steel. 1898.”

Philippines President Manuel Quezon, a tubercular with a hacking cough, had left Manila earlier, unrecognized in an American army uniform and steel helmet. Parting with his loyal executive secretary Jorge Vargas, Quezon instructed him to wait in Manila for the Japanese and secure the best deal for the city he could. “You have my absolute confidence, and I am sure you will not fail me.” On orders, Vargas was to cooperate with the occupation short only of taking an oath of allegiance to the Japanese Empire.

“Mr. President,” said Vargas, “no matter what happens, you can count on me, whether in Malakanyang [Palace] if the Japanese allow me to remain, or in my house in Kawilihan.”

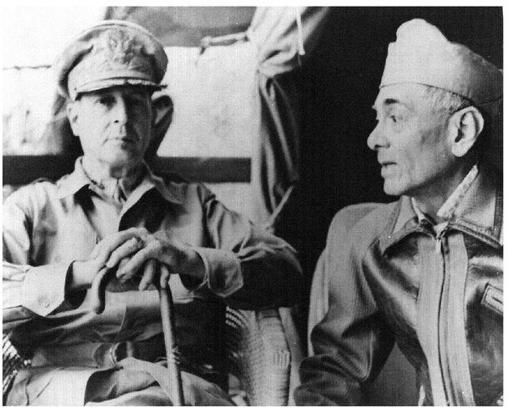

General Douglas MacArthur and ailing President Manuel Quezon, who had been evacuated from Manila.

Courtesy MacArthur Memorial Library & Archives

Two launches took Quezon’s party to the

Mayon,

almost a mile out in the bay, now delayed in departure because the ship’s chief engineer had gone back into Manila to pack his clothes. Impatient and worried about new raids on the harbor, Quezon ordered the

Mayon

’s crew to sail with or without the absent engineer. Vincente Madrigal, the shipowner, ordered the third engineer to fire the engines, and the ship soon lifted anchor. By dusk Quezon was at the Corregidor pier saluted by a Filipino guard of honor. But the guard of honor had a more urgent purpose. Quezon had not needed much urging from MacArthur to order truckloads of crated gold and silver bullion from the Philippines treasury rushed under heavy guard to dockside for storage in a Corregidor tunnel.

Outside military and government offices in the city, bonfires of papers from abandoned files were still burning. On the waterfront at Cavite, oil storage tanks, put to the torch, spewed heavy black smoke into the night. What was left of the navy, but for three gunboats, six PT boats, and Admiral Hart’s submarines, set off after dark for Java. A few patched-up P-40 fighters had been flown to Corregidor’s postage-stamp Kindley Field. On departure MacArthur handed Carlos Romulo, his Philippine assistant for press relations, a sealed envelope—the Open City declaration for Manila.

Blacked-out Corregidor was only thirty miles from the mainland at Cavite, but before the

Don Esteban

reached the island’s North Dock, little Arthur announced that he was tired and wanted to go home. Home, however, would be Corregidor, where Major General George Moore, the commandant, greeted the MacArthurs and escorted them toward cots in a tunnel. MacArthur announced that he would not live in a dank tunnel. “Where are

your

quarters?” he asked. At Topside, said Moore. (There was also Middleside and Bottomside, identifying the heights of the Rock.) “We’ll move in there tomorrow morning,” said his superior. But the house is exposed to air attacks, Moore warned. “That’s fine,” said MacArthur. “Just the thing.” Neither the house nor the arrangement would last very long.

No churchgoer in any denomination, although he often quoted Scripture in his speeches and proclamations, MacArthur did not attend midnight Christmas Mass. Open to Filipinos as well as Americans, it was celebrated by Catholic service chaplains in the Malinta Tunnel, which penetrated the Rock.

“I RECEIVED WORD THIS MORNING,” Stimson wrote, wondering when if ever the Prime Minister slept, “that Churchill was anxious for a talk with me on the subject of the Philippines, so I spent the first part of the morning preparing for that besides attending to my other administrative work. I then went over to the White House with [Brigadier] General Eisenhower of the War Plans Division to back me up in case I was asked questions that I couldn’t answer.” Churchill had already improvised the map room near his bedroom, where the three talked about the Philippines. The morning papers had reported that the Japanese had landed a “strong force” by forty troopships south of Manila and were already closing in on the capital from Lingayen Gulf to the north. The Lamon Bay force, landing at the narrow neck of central Luzon, numbered only eight thousand, far inferior except in desire from MacArthur’s US and Filipino troops who, the general had reported dramatically, were standing off the enemy “against great odds.” In actuality they were withdrawing, north and south, toward Bataan. Supplies that might have been prudently stockpiled earlier on “the Rock” were abandoned, including those dockside at Cavite. Tokyo Radio described the ongoing retreat into Bataan as “a cat entering a sack.”

ROMINTEN, a heath in East Prussia that was a favorite hunting ground for

Reichsmarschall

Hermann Göring, was close to Hitler’s headquarters and as close to the Russian front as Göring was likely to venture. His air commander on the Eastern Front, Colonel-General Wolfram von Richthofen, came to ask permission to have

Luftwaffe

troops unneeded in the winter weather made available for infantry duty. “They must fight, win, or die where they stand,” Göring insisted, accusing him of “whining.” Nevertheless he went with Richthofen from “Robinson,” the curiously christened air force forward headquarters nearby, to

Wolfsschanze

to let the general make the same case to Hitler. “The

Reichsmarschall

and I were very persuasive,” von Richthofen noted in his diary. “

Führer

swears loudly about the army commanders responsible for much of this mess.” Warily, Göring visited Hitler only once more during the winter, on December 27. Otherwise he remained at his vast Prussian estate, “Carinhall,” bursting with art treasures looted from Holland, France, and other occupied countries. “For days now the

Reichsmarschall

has vanished,” General Hoffmann von Waldau, the deputy air chief, wrote from “Robinson” on Christmas Eve. “

He

gets to spend Christmas at home. It’s important to set an example in little things. We are going to have to get used to harder times.” Yet Waldau himself would venture no farther forward than East Prussia.

ABOARD THE

Regnbue,

with the convoy still roughly in formation, chatter abounded about Christmas Eve dinner for the crew, its scheduled time changing as they moved westward across the time zones. “Rumors,” A. J. Liebling wrote, “were spread by one of the British machine gunners, who had talked to the third engineer, who had it straight from a messboy, that there would be turkey. While the convoy moved along at its steady ten knots, nobody aboard the

Regnbue

talked of anything but the coming dinner.” On the great night the captain’s table in the saloon was laid for a dozen places—officers, the radioman, a gunner, and Liebling. To mark the occasion, as there were no alarms about subs or planes and the sea was still calm, the officers wore neckties. Engineer Larsen raised a glass of gin and pronounced “Skoal!” Then came a thick soup with canned shrimp and crabmeat, after it fish pudding. The turkey was brought in ceremoniously by the steward “with the pride of a Soviet explorer presenting a hunk of frozen mammoth excavated from a glacier.”