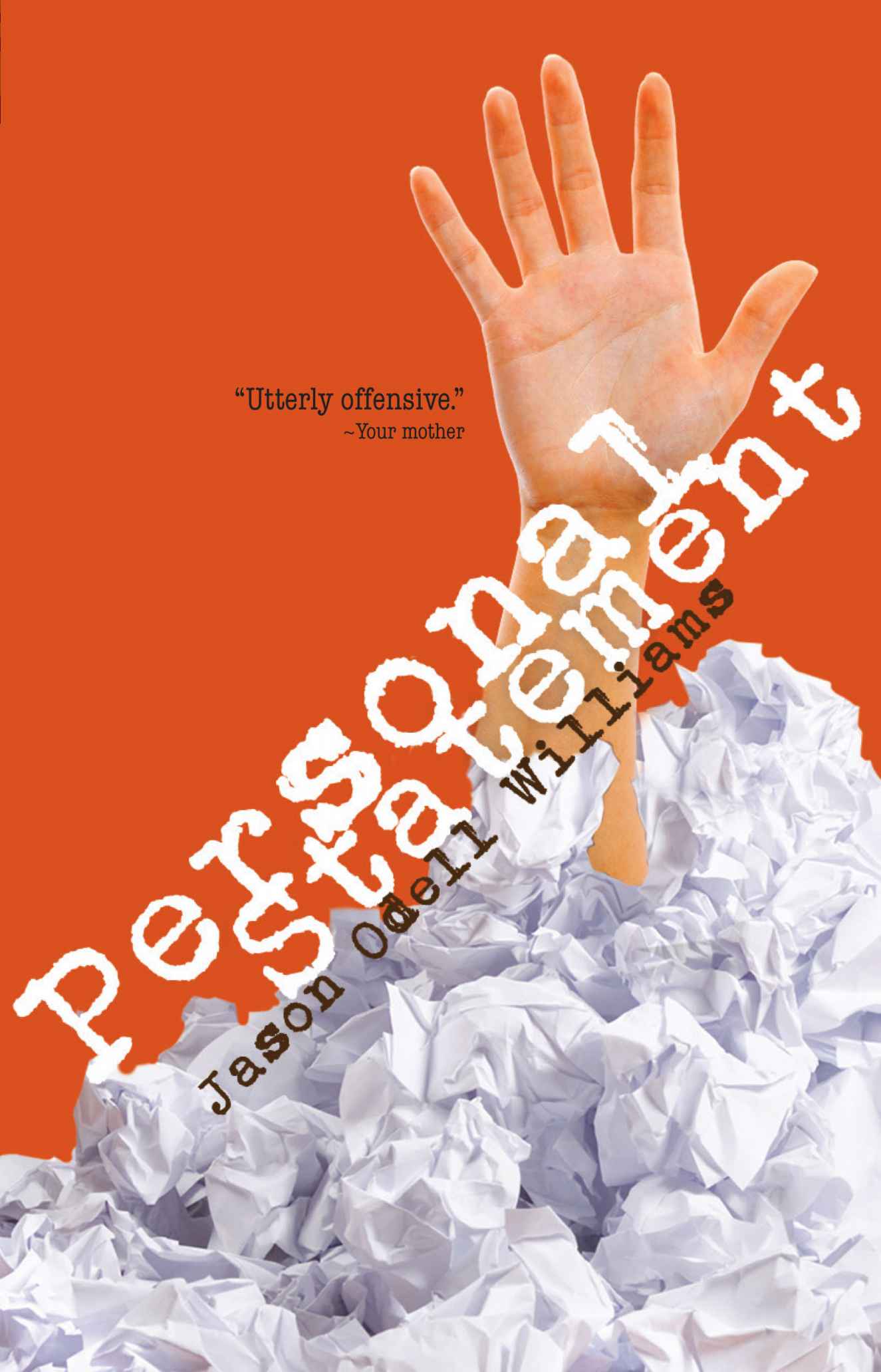

Personal Statement

Read Personal Statement Online

Authors: Jason Odell Williams

Personal Statement

“For the striver and slacker in all of us,

Personal Statement

hits deliciously close to the bone with a mordantly hilarious satire of resume-polishing and ambition. For anyone who ever inflated a title, or wished they did. A page-turning delight!” —Sarah Ellison,

Vanity Fair

Contributing Editor and author of

War

at the

Wall Street Journal

Personal Statement

hits deliciously close to the bone with a mordantly hilarious satire of resume-polishing and ambition. For anyone who ever inflated a title, or wished they did. A page-turning delight!” —Sarah Ellison,

Vanity Fair

Contributing Editor and author of

War

at the

Wall Street Journal

“Personal Statement

is a hilarious take on the merciless winner-take-all world of college applications. A wild book.” —Tony d’Souza, author of

Mule

is a hilarious take on the merciless winner-take-all world of college applications. A wild book.” —Tony d’Souza, author of

Mule

“Jason Odell Williams’

Personal Statement

is a fast-paced, delightful read. As a parent and a professor, I can say that Mr. Williams’ satirically savvy take on the absurdities of the college admissions process is deliciously accurate. And yet his wickedly funny portrayal of four ambitious twenty-somethings is never mean-spirited.

Personal Statement

should be on the required reading list for all High School guidance counselors, college-bound seniors and their parents!” —Richard Warner, Professor, University of Virginia

Personal Statement

is a fast-paced, delightful read. As a parent and a professor, I can say that Mr. Williams’ satirically savvy take on the absurdities of the college admissions process is deliciously accurate. And yet his wickedly funny portrayal of four ambitious twenty-somethings is never mean-spirited.

Personal Statement

should be on the required reading list for all High School guidance counselors, college-bound seniors and their parents!” —Richard Warner, Professor, University of Virginia

“Don’t tell the person you hired to take the SATs for you that you are reading

Personal Statement

! This delightful book has a lot of fun with college mania. You will, too.” — Gregg Easterbrook, author of

The Leading Indicators

Personal Statement

! This delightful book has a lot of fun with college mania. You will, too.” — Gregg Easterbrook, author of

The Leading Indicators

“A fearless thrashing of American ambition in the Millennial age.” —Michelle Miller, author of

The Social Network

The Social Network

“Hilarious and stunningly accurate. If you were ever a teenager, read this book!” — Mathew Goldstein, 20, Saint Paul, MN

“Hilarious, authentic, poignant portrayal of pre-college angst and ambition. Williams serves up delicious, right-on characterizations with wit, precision, and sympathy. Intensely contemporary, yet timeless. A must-read for college-bound teens and their parents!” — Dr. Judy Rubin, Pediatrician, Maryland

Jason Odell Williams

In This Together Media

New York

In This Together Media Edition, July 2013

Copyright ©2013 by In This Together Media

All rights reserved. This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Published in the United States by In This Together Media, New York, 2013

BISAC:

1. Friendship (social issues) – Juvenile Fiction. 2. Humor– Juvenile Fiction. 3. School and Education – Juvenile Fiction. 4. Gay and Lesbian – Juvenile Fiction

ISBN: 978-0-9858956-7-9

ebook ISBN: 978-0-9858956-6-2

Cover design by Nick Guarracino

Ebook design by Steven W. Booth

For my parents, who taught me everything I know

(including everything I learned in high school and college, because they paid for it)

The sea hath bounds, but deep desire hath none.

— Wm. Shakespeare

Back in 1978, the college application process seemed pretty straightforward. I requested paper applications from the schools that interested me (with little or no guidance from any school officials); I took the SAT once with absolutely no preparation; and I dashed off my applications with only modest effort. The endeavor was quick and painless. And it resolved several months later with the arrival of several acceptances, a few rejections, and a simple decision: where did I want to head in the fall?

Today's high school students tell a vastly different story. For some, it is a process that begins almost at birth as parents agonize over preschool waitlists. For others, the pressure ramps up steeply in middle school, as students and their families begin to hear daunting speculation about what colleges are looking for in their flooded applicant pool.

For starters: a report card with only the most difficult classes listed—and unblemished by any grades below an A. Perfect standardized test scores. Playing on a school's varsity sports team. Leadership within the school community. Hours spent volunteering or organizing service projects. A special talent or skill to distinguish each applicant. A sincere, honest account of why the student finds a particular school to be his or her “perfect match”. And most important? The personal statement: a finely honed, touching, authentic representation of a student’s uniqueness and personality. It’s a reassurance to admissions officials that in a student's quest for perfect well roundedness he or she has also developed a singular voice and a knack for pithy self-expression.

It’s a tall order, to say the least.

In many American homes, the importance of getting into a top school is drilled into children from such a young age that by the time they are applying to college, every decision in their lives will have been made with college in mind. Enrolling in soccer camp? No, the time is better spent with a math tutor. Interested in poetry? Take Advanced Placement English Literature instead and forego the “less competitive” poetry elective. Content to play third-chair violin? Enroll in extra lessons on Saturdays and maybe the orchestra director will move you to first chair. For too many children, this kind of calculated competition and relentless drive toward “achievement” is woven into the very fabric of their daily lives, in school and out. It’s all they know and is the only foothold they have in an overwhelming process.

That is, unless they’re lucky, and they stumble upon a magical, life-changing experience that lends itself—perhaps a little too perfectly?—to the college application wildcard: the personal statement.

As a mother of three observing my children and their peers, I see the toll that our cultural obsession with perfection—often in meaningless and manufactured categories—takes on our kids. And I see, increasingly, that even those who receive top grades and test scores and admission at elite colleges are often left unprepared for life after school. More tragically, too many students remain unhappy and anxious, trapped in a schooling system that values “achievement” and “success” more than curiosity, mental health, and engagement.

Spurred by the toxic culture I saw around me, I directed a documentary called

Race to Nowhere

that closely examines our educational system and the impact our collective, narrow vision of school success has on the health and happiness of our children. What I discovered was heartbreaking. Students were taking extreme measures to live up to impossibly high expectations, and they were suffering—in body and mind. I was overwhelmed with stories of students sacrificing sleep or meals to study, or engaging in other self-destructive behavior when they saw no way off the academic treadmill.

Race to Nowhere

that closely examines our educational system and the impact our collective, narrow vision of school success has on the health and happiness of our children. What I discovered was heartbreaking. Students were taking extreme measures to live up to impossibly high expectations, and they were suffering—in body and mind. I was overwhelmed with stories of students sacrificing sleep or meals to study, or engaging in other self-destructive behavior when they saw no way off the academic treadmill.

Personal Statement

captures the insanity of the college application process. An apt and wry commentary, the book’s narratives echo the all too real stories I have heard from students across the country, while managing to poke fun at the cutthroat, competitive model of education in which we’ve become unwilling participants. Through the fictional stories of three high schoolers, we see how each deals with the onslaught of cultural, parental, and societal pressure to achieve admission to a top college—and how each musters a different approach to managing that stress. In the end, the characters’ shared quest to volunteer as aid workers in the heart of a coming hurricane is perfect satire: a fictional situation exaggerated just gently enough that it lets us see reality in a new light. As readers, we’re forced to ask ourselves: how have we arrived at a cultural moment in which, “How will this look on my college application?” has become a more important question than, “How can I help?” or, “What will keep me safe?” or, “What makes me happy?”

captures the insanity of the college application process. An apt and wry commentary, the book’s narratives echo the all too real stories I have heard from students across the country, while managing to poke fun at the cutthroat, competitive model of education in which we’ve become unwilling participants. Through the fictional stories of three high schoolers, we see how each deals with the onslaught of cultural, parental, and societal pressure to achieve admission to a top college—and how each musters a different approach to managing that stress. In the end, the characters’ shared quest to volunteer as aid workers in the heart of a coming hurricane is perfect satire: a fictional situation exaggerated just gently enough that it lets us see reality in a new light. As readers, we’re forced to ask ourselves: how have we arrived at a cultural moment in which, “How will this look on my college application?” has become a more important question than, “How can I help?” or, “What will keep me safe?” or, “What makes me happy?”

In a society where so many kids and families have accepted busyness as a norm, it’s refreshing to find a book that inspires us to think deeply about how we can create a healthier educational culture for our children. And it’s invigorating to see such a call to action come in the form of smart humor and playful self-deprecation—a reminder that perhaps it’s thinking too seriously and too single-mindedly that set us down our current path of competition in the first place.

Personal Statement

is a must-read for parents, educators, counselors, and students. It pushes all of us to rethink the impact of our current educational system on our children. And it urges us to advocate for a new college admissions process. One that replaces the standardization of test taking with the liberty of true learning and inquiry, one that trades padded college resumes for the spirit of aspiration, growth, and new challenge, and one reshaped in light of these honest educational markers.

is a must-read for parents, educators, counselors, and students. It pushes all of us to rethink the impact of our current educational system on our children. And it urges us to advocate for a new college admissions process. One that replaces the standardization of test taking with the liberty of true learning and inquiry, one that trades padded college resumes for the spirit of aspiration, growth, and new challenge, and one reshaped in light of these honest educational markers.

That kind of transformation would make a statement indeed.

Vicki Abeles with Shelby Abeles

August 1, 2013

Vicki Abeles is a filmmaker, attorney and advocate for children and families. She directed the acclaimed documentary “Race to Nowhere,” which challenges common assumptions about how children are best educated and launched a social action campaign dedicated to providing resources and tools to support action connected to the film. Abeles is also the co-author of the

End the Race Companion Book

for parents, educators and students. Her oldest daughter, Shelby Abeles, is currently a student at Wellesley College in Massachusetts. She has two other children, Jamey and Zak, both high school students.

End the Race Companion Book

for parents, educators and students. Her oldest daughter, Shelby Abeles, is currently a student at Wellesley College in Massachusetts. She has two other children, Jamey and Zak, both high school students.

BETTERED EXPECTATION

EMILY KIM

I fucking hate Emily Kim.

Let me clarify. Yes, my name is Emily Kim. But this is not about hating myself. I have no doubts or self-loathing. I love me. I’m awesome.

I hate the

other

Emily Kim. “Stanford-Emily Kim.” The bitch who’s been making me look bad for almost a decade. The one my parents say I should aspire to be. The one they secretly wish was

their

child. The one whose yellowed photo and article from

The

New York Times

is still clipped to our fridge—taunting me whenever I get my morning OJ. The one my mother chides me about at least twice a day.

other

Emily Kim. “Stanford-Emily Kim.” The bitch who’s been making me look bad for almost a decade. The one my parents say I should aspire to be. The one they secretly wish was

their

child. The one whose yellowed photo and article from

The

New York Times

is still clipped to our fridge—taunting me whenever I get my morning OJ. The one my mother chides me about at least twice a day.

“She go far in life. And her parents no have pay tuition. She be doctor in no time. Family very proud. You be like her, Emily!”

So even though I’m one of the top students at Fairwich Academy (arguably the best all-girls private school in Connecticut), my parents still push me to do more, be more, achieve more. I think it stems from their inferiority complex about how they got their money. Most of the families around here, aside from being whiter than a paper towel (and about as fun, too), are seriously

old

-money. Their houses have been handed down for generations and their kids come from a long line of people named Chip who sail and play croquet and use “summer” as a verb. My parents are FOB Koreans who made their mark with an insanely successful chain of dry cleaners (Eco-Pure Cleaners—the very first in the state to “go green”). Our house is just as big, our cars are just as fancy, and I pay full tuition like everyone else. But because my parents are immigrants who “run a store” and aren’t in one of the more socially acceptable professions (banker, hedge funder, trust funder), we will never be fully accepted into the Fairwich elite. Which is fine by me. Bunch of assholes anyway. But it doesn’t stop me from wanting to go where the elite kids will go: to the Ivy League. And it doesn’t stop me from wanting to be better than the best: Stanford-Emily Kim.

old

-money. Their houses have been handed down for generations and their kids come from a long line of people named Chip who sail and play croquet and use “summer” as a verb. My parents are FOB Koreans who made their mark with an insanely successful chain of dry cleaners (Eco-Pure Cleaners—the very first in the state to “go green”). Our house is just as big, our cars are just as fancy, and I pay full tuition like everyone else. But because my parents are immigrants who “run a store” and aren’t in one of the more socially acceptable professions (banker, hedge funder, trust funder), we will never be fully accepted into the Fairwich elite. Which is fine by me. Bunch of assholes anyway. But it doesn’t stop me from wanting to go where the elite kids will go: to the Ivy League. And it doesn’t stop me from wanting to be better than the best: Stanford-Emily Kim.

Eight years ago, Stanford-E.K. became the poster child for how A-list volunteer work could give students virtual celebrity status, and how the Ivies would bludgeon each other for the right to grant enterprising students like her admission. Before Katrina even hit the Gulf Coast, Stanford-E.K., then just a sophomore with a one-month old driver’s license, was in her Subaru Outback racing down Interstates 81 and 59. By morning, while the city was still dazed and confused, Stanford-E.K. was at Charity Hospital on Tulane Avenue shining flashlights for surgeons and helping evacuate patients. But she didn’t stop there. Two years later, the bane of my existence traveled back to the 9th Ward to build green homes. Someone snapped a pic of her passing a 2 x 4 to Brad Pitt and posted it on Facebook, tagging E.K. The pic went viral and before she even returned home to Connecticut her mom called her cell to report that there were ten voice mails from top schools across the country begging her to attend

their

university. (Notably

not

Harvard, by the way. Take that, E.K.!) She chose Stanford and the rest is history.

their

university. (Notably

not

Harvard, by the way. Take that, E.K.!) She chose Stanford and the rest is history.

But it’s not only her annoying fairy tale-like story—one that I swear was written by some covert Hollywood producer her parents hired. It’s that no matter what I do, it’s never enough. I’ve been the lead in every musical at Fairwich Academy since freshman year, was studying Linear Algebra and Game Theory at Sarah Lawrence College while in 10th grade, and just recently returned from a highly productive July in Korea where I interned with high-level government officials on issues surrounding the country’s notorious dealings in the sex-slave trade. (It’s a seriously fucked up situation, by the way. Do

not

get lost in South Korea.)

not

get lost in South Korea.)

But even with my amazing successes in and out of school, all my one-dimensional mother can remember is the B that I got in AP English last term. (I’m sorry, but

Tess of the d’Urbervilles

is a horrible book about horrible, boring people, and it’s sort of a borderline defense of rape. But I guess Mr. Harper didn’t agree with my opinion or my final essay, “Legitimate Rape for Dummies.”)

Tess of the d’Urbervilles

is a horrible book about horrible, boring people, and it’s sort of a borderline defense of rape. But I guess Mr. Harper didn’t agree with my opinion or my final essay, “Legitimate Rape for Dummies.”)

Anyway, that one blemish on an otherwise spotless academic career has me keyed up about the college application process a bit more than usual. And my admittedly unhealthy obsession with Stanford-E.K. is in full hyperdrive.

“How do we compete with her? How do we compete with Brad Pitt? It’s like she’s out to ruin my life!”

I say this to my best friend Rani, who sort of shrugs but doesn’t roll her eyes. I could kill her for being so patient with me.

We’re sitting outside the Pinkberry on Fairwich Avenue, sharing a Mini Original with mango slices, raspberries, and dark chocolate crispies. (Doctors say dark chocolate has healthy heart benefits, okay, so shut up about it.) It’s hot and sticky out here, even for August. With Labor Day less than three weeks away, most of Connecticut’s elite are still beating the heat at their summer homes on Nantucket or Martha’s Vineyard. For most of the rising seniors in our class, that means lazy days tanning and drunken nights hooking up.

Except for girls like Rani and me, girls with our eyes on the prize: Harvard, Yale, National Merit Scholarships, winning the Siemens Competition.

But for me, the honor I covet most, the granddaddy of them all, the Gates Millennium Scholars Program…? That’s the only one that seems completely out of my reach.

“God, I would KILL to be black! Or Hispanic. Or Alaskan, even. Ugh!”

Before Rani thinks I’m a total racist, I quickly explain that because of the onslaught of over-achieving Asians in America, great scholarships like the Gates Millennium Scholars Program don’t find high-achieving Korean-American students quite as compelling as African American, American Indian/Alaska Native, or Hispanic American students.

“You are SO lucky to have your complexion,” I say looking at her golden brown skin, which falls somewhere between russet and sienna. “You could make a long braided ponytail, totally pass for Native American, and walk right into

Dartmouth.

Me…? The only thing anyone ever confuses me for is Chinese. And I’m nowhere

close

to being Chinese. Did you see the Olympics? Those bitches are insane. I’m Korean-American!”

Dartmouth.

Me…? The only thing anyone ever confuses me for is Chinese. And I’m nowhere

close

to being Chinese. Did you see the Olympics? Those bitches are insane. I’m Korean-American!”

So okay, yeah, I’m a

little

bit racist. But at least I’m up front about it.

little

bit racist. But at least I’m up front about it.

I don’t mean to sound bitter or upset. I’ve got it pretty sweet. But I worked my ass off to get here. And I’m in excellent shape going into our final year of high school. It’s just that the bar for girls like me keeps getting raised. A perfect SAT score, 5.0 GPA, and killer extracurriculars are nowhere near enough.

“What we need,” I tell Rani, “is a killer personal statement.”

The personal statement is what separates the men from the boys, the ladies from the whiny bitches. Nowadays,

everyone

applying to top schools has the credentials on paper. But life experience… frontline, in the trenches, blood-on-your-shirt and sweat-in-your-eye life experience… that’s the

only

way to stand out these days. Especially for me. Not only am I competing against thousands of highly qualified candidates. I’m also competing against hundreds of Emily Kims. Not metaphorically. Literally.

everyone

applying to top schools has the credentials on paper. But life experience… frontline, in the trenches, blood-on-your-shirt and sweat-in-your-eye life experience… that’s the

only

way to stand out these days. Especially for me. Not only am I competing against thousands of highly qualified candidates. I’m also competing against hundreds of Emily Kims. Not metaphorically. Literally.

It’s bad enough to be saddled with one of the world’s most common last names. (For every Smith and Johnson there are 25 Kims.) But to compound the problem by

also

having one of the most popular

first

names for Asian-American girls? Who, by the way, are all concert cellists halfway through med school before they can even

drive

! Why couldn’t my parents have named me something WASP-y to balance the world’s most Asian last name?

also

having one of the most popular

first

names for Asian-American girls? Who, by the way, are all concert cellists halfway through med school before they can even

drive

! Why couldn’t my parents have named me something WASP-y to balance the world’s most Asian last name?

“I always thought I was more of a Madison or a… what’s WASP-ier than Madison?”

“Morgan,” says Rani, unable to hide her contempt. Names are a sore subject for her as well. Her mother is first-generation Indian-American. Her dad’s family was on the Mayflower and he’s like the

definition

of WASP. When they had their first child, they named her Morgan, so that when the time came for her to go to private nursery school, even with her skin four shades darker than her lily-white toddler classmates, she would fit in.

definition

of WASP. When they had their first child, they named her Morgan, so that when the time came for her to go to private nursery school, even with her skin four shades darker than her lily-white toddler classmates, she would fit in.

But four years later, when their next daughter was born, Mrs. Caldwell had a sudden sense of nostalgia for her heritage. She wanted her daughter’s name to reflect her multi-cultural background. So they named her “Rani.” Four simple letters, yet surprisingly difficult for white people to pronounce. (For the record it is pronounced ‘RAH-nee’ and sounds exactly like the American boy’s name, ‘Ronnie.’)

“At least everyone knows you’re a girl,” Rani says. “I sound like some meathead dude who likes Captain America and WrestleMania. ‘Hey, Ronnie—wanna go to Comic Con this year?’ ‘Totally Awesome, man, I’m in.’” Rani says all of this with the flat inflection of a DMV employee. God, I love this girl. She’s the only one who gets me. And the only one who shares my passion for academic excellence without being a total “Dr. Who” geek. (Though that

is

a pretty cool show—I just don’t have time to watch TV anymore).

is

a pretty cool show—I just don’t have time to watch TV anymore).

Rani finishes off the last chocolate crispy and commiserates with me about the dilemma we face. And that’s when I realize we need to think of something huge, something monumentally impressive that will separate

our

college applications from rest of the pile.

our

college applications from rest of the pile.

“What we need is a moment like Stanford-Emily Kim’s. When that bitch’s Facebook pic changed from her birthing those calves in Nigeria to her passing lumber down the line to Brad Pitt? That noise went viral faster than the Chocolate Rain kid.”

“I loved that Chocolate Rain kid,” Rani says, cracking her first smile of the day.

“We need to find something that will get us

that

kind of exposure,” I say, unwavering. “What we need is another Katrina.”

that

kind of exposure,” I say, unwavering. “What we need is another Katrina.”

I. Hate. Martha’s. Vineyard.

My family has been coming here since the dawn of time. Not really. But it feels like it. They like to brag to anyone who doesn’t know—and plenty of people who’ve heard the story multiple times—that “the Clintons have been free men since the mid-18th century, long before the Emancipation.”

I guess my great-great-great-great-great-great grandparents were such good people that their owners simply

granted

them their freedom. Or granny was humping the white man and he felt guilty. But either way, we’re still black and proud and all that jazz. So proud that my parents insist on summering in Oak Bluffs every year, where all of the fancy black families go. I guess it makes them feel good to see so many “brothers and sisters” here living the dream, the embodiment of the African-American success story. But who are they kidding? It’s not

that

black. I mean, Oak Bluffs is not Detroit. (It’s not even Baltimore.)

granted

them their freedom. Or granny was humping the white man and he felt guilty. But either way, we’re still black and proud and all that jazz. So proud that my parents insist on summering in Oak Bluffs every year, where all of the fancy black families go. I guess it makes them feel good to see so many “brothers and sisters” here living the dream, the embodiment of the African-American success story. But who are they kidding? It’s not

that

black. I mean, Oak Bluffs is not Detroit. (It’s not even Baltimore.)

The Vineyard isn’t all bad though. Most days I hitch a ride down to Gay Head (insert homosexual joke here), where the vibe is more relaxed and you can actually be yourself (in more ways than one, plus the nude beach is spectacular!) But sincerely, it’s the only town on this bitch of a rock where the people don’t talk with their lower jaw permanently jutting forward. And that includes the black folk.

Yet every year my parents trek to the Vineyard. They even have one of those gag-me-with-a-spoon bumper stickers on their Mercedes GL 550. You know the black and white oval with the letters MV inside? (How pretentious is that?) We drive from Westport in our massive SUV, but park it landside and take the passenger ferry over. My father has a restored 190-SL convertible that we use for “island driving only.” (Even

more

pretentious, I know.)

more

pretentious, I know.)

Sometimes I think I was born in the wrong decade. I’m nothing like my parents or my peers. I should have been born in the 80s. I love The Cure and Ronald Reagan, Freddy Mercury and the movie

Wall Street

(plus any movie made by John Hughes). I’m basically the black Alex P. Keaton with exquisite taste in clothes and a love of retro music.

Wall Street

(plus any movie made by John Hughes). I’m basically the black Alex P. Keaton with exquisite taste in clothes and a love of retro music.

Yet here I am. Stuck in this 4,500 square foot summer home, ostensibly working on my college essay, but really flipping through

Details

magazine and daydreaming about my gorgeous roommate Mac (who hugged me goodbye for the first time when we left for summer break; I’ve been reliving those precious two seconds in my mind ever since) while my parents cavort with other rich Vineyarders at ostentatious cocktail parties, raising money for Haiti or Africa or whatever third-world flavor of the month has been making the rounds on CNN.

Details

magazine and daydreaming about my gorgeous roommate Mac (who hugged me goodbye for the first time when we left for summer break; I’ve been reliving those precious two seconds in my mind ever since) while my parents cavort with other rich Vineyarders at ostentatious cocktail parties, raising money for Haiti or Africa or whatever third-world flavor of the month has been making the rounds on CNN.

I was going to join my parents but bowed out at the last minute, feigning an upset stomach. My father said, “Might be a good time to work on that college essay. Yale doesn’t accept

every

legacy, you know.”

every

legacy, you know.”

Yes, Dad, I know, because you’ve been telling me since fifth grade! And whoever said I

wanted

to go to Yale?! Just because you and mom did. New Haven is the Pittsburgh of Connecticut. Plus, it’s only forty minutes from our house in Westport—and fifteen minutes from my stupid high school. So not only would I be forced to spend another four years in basically the same crappy city, I’d have to see

you

every weekend. So, no. Yale. Is

not

happening. Sorry, Dad.

wanted

to go to Yale?! Just because you and mom did. New Haven is the Pittsburgh of Connecticut. Plus, it’s only forty minutes from our house in Westport—and fifteen minutes from my stupid high school. So not only would I be forced to spend another four years in basically the same crappy city, I’d have to see

you

every weekend. So, no. Yale. Is

not

happening. Sorry, Dad.

Besides… I’ve got my sights set higher than that. Well,

farther

would be more accurate. Some place where English isn’t the official language and the buildings are older than our ancestors in the cotton fields. And it will happen. Despite your veiled threats to refuse to finance any university

other

than Yale. And Mom’s good cop routine isn’t working either.

farther

would be more accurate. Some place where English isn’t the official language and the buildings are older than our ancestors in the cotton fields. And it will happen. Despite your veiled threats to refuse to finance any university

other

than Yale. And Mom’s good cop routine isn’t working either.

“Don’t listen to your father,” she said to me last week. We were standing in our enormous gourmet kitchen having a heart-to-heart. (I hate heart-to-hearts.) “You can go to

any

school you want… as long as it’s an Ivy. Or Stanford. I don’t think he’d have a problem with Stanford.”

any

school you want… as long as it’s an Ivy. Or Stanford. I don’t think he’d have a problem with Stanford.”

“What about a school,” I offered enthusiastically, “that isn’t

technically

in the Ivy League, or here in the Northeast, but

is

highly regarded as one of

the

best universities in the world?”

technically

in the Ivy League, or here in the Northeast, but

is

highly regarded as one of

the

best universities in the world?”

“…Didn’t I say Stanford was okay?”

“It’s not in America.”

My father heard that and marched in from the study to nip our conversation in the bud. “No, unh-uh. I

refuse

to finance a four-year European vacation so you can study seventeenth-century poetry and

find yourself!

You’re not Richard Wright!”

refuse

to finance a four-year European vacation so you can study seventeenth-century poetry and

find yourself!

You’re not Richard Wright!”

And that was one of the more civilized discussions about my future academic life.

Of course I’ve researched scholarships abroad—so I wouldn’t need money from my parents. There’s one to La Sorbonne called the James Baldwin Fellowship—named after the famous expatriate author of

Giovanni’s Room

and

Go Tell It on the Mountain

—that offers a full ride plus housing and a stipend to “African-American students who exemplify Mr. Baldwin’s spirit and passion for the written word.” A seemingly perfect fit for me!

Giovanni’s Room

and

Go Tell It on the Mountain

—that offers a full ride plus housing and a stipend to “African-American students who exemplify Mr. Baldwin’s spirit and passion for the written word.” A seemingly perfect fit for me!

But even with my impeccable grades and my amazing list of awards, clubs, and special skills, plus what’s sure to be the most dynamic and powerful personal statement

ever

(the essay portion of the scholarship application is rumored to account for more than

half

of their decision), I’m just a run-of-the-mill applicant. The competition for the Baldwin Fellowship is fierce. I need that

one

extra ingredient that sets me apart. An extraordinary angle that no one else has. Something… epic.

ever

(the essay portion of the scholarship application is rumored to account for more than

half

of their decision), I’m just a run-of-the-mill applicant. The competition for the Baldwin Fellowship is fierce. I need that

one

extra ingredient that sets me apart. An extraordinary angle that no one else has. Something… epic.

But I can’t think of what that might be. And time is running out.

So here I sit, miserable and alone, likely consigned to four more years in New Haven, the

Details

magazine tossed aside, the Weather Channel on in the background for its soothing repetitiveness, and my laptop open with the words “Baldwin Fellowship Essay” at the top of an otherwise blank page, the blinking cursor mocking me with every flash.

Details

magazine tossed aside, the Weather Channel on in the background for its soothing repetitiveness, and my laptop open with the words “Baldwin Fellowship Essay” at the top of an otherwise blank page, the blinking cursor mocking me with every flash.

And then it happens.

The third-string Asian guy chirps from the flat screen that the National Weather Service has upgraded a storm system 150 miles off the east end of Long Island. In less than an hour it went from a Tropical Storm to a Category 2 Hurricane. He says it’s the most powerful system since Andrew and it’s building faster than any weather event he’s ever seen in that part of the Atlantic. And now it’s turning toward New England. Projections indicate it will make landfall near the border of Rhode Island and Connecticut in just over 36 hours. The town most likely to take a direct hit: Cawdor, Connecticut.

In a flash, the idea hits me. I scrawl a note for my parents and tape it to the espresso machine, where I know they’ll see it. I grab the GL keys (the car parked

off

the island—I’m not crazy enough to take my dad’s vintage convertible), toss my laptop and a few necessities into a backpack, and scramble down Lake Avenue, barely catching the Oak Bluffs to Woods Hole passenger ferry at 6:15 p.m. As the boat chugs across Vineyard Sound, I pull up Google Maps on my iPhone 5 and set a course for Cawdor.

off

the island—I’m not crazy enough to take my dad’s vintage convertible), toss my laptop and a few necessities into a backpack, and scramble down Lake Avenue, barely catching the Oak Bluffs to Woods Hole passenger ferry at 6:15 p.m. As the boat chugs across Vineyard Sound, I pull up Google Maps on my iPhone 5 and set a course for Cawdor.

Looking out at the choppy waves spraying their foam on the port side, I can only thank the Muses for the inspired idea since it’s really quite uncharacteristic of me. It goes like this: Race to Hurricane Ground Zero before the storm hits; be part of the volunteer rescue effort; write the most impressive essay in the history of the Baldwin Fellowship; win the scholarship abroad; never have to summer with my parents on the Vineyard again.

Rather elegant, dontcha think?

And as Mr. Baldwin himself discovered, Paris is a better place for a young black man with a love of fashion, music, and other men. In America, I’m a joke. In Europe, I’ll be an inspiration.

I hate golf.

I hate the etiquette. I hate how long it takes. I hate the stupid skirts I have to wear.

But I put up with it. I smack a tiny ball around miles of grass for five hours because it’s part of my job. It’s why I’m here right now, with Governor Charles Watson of Connecticut and his chief of staff, Teddy Hutchins. They invited me to the Wampanoag Country Club (a place I’d normally

despise

—not only for the Native-American man that is their logo, but because I suspect I’m the only person of Jewish descent on the grounds today), and I humbly accepted their invitation. Some people like to have meetings out of the office to lessen the formality. Coffee, lunch, or a quick nine with the governor to discuss joining his team for the next election cycle. He apparently didn’t want to raise any eyebrows by meeting me in public. (I also heard he was anxious to get me on the links once he discovered I had a 4.2 handicap.)

despise

—not only for the Native-American man that is their logo, but because I suspect I’m the only person of Jewish descent on the grounds today), and I humbly accepted their invitation. Some people like to have meetings out of the office to lessen the formality. Coffee, lunch, or a quick nine with the governor to discuss joining his team for the next election cycle. He apparently didn’t want to raise any eyebrows by meeting me in public. (I also heard he was anxious to get me on the links once he discovered I had a 4.2 handicap.)

So I go with the flow, go where the opportunities are. I’m in the boys’ club of politics and I have to play their game. And I play it well.

“Get left,” I say nonchalantly after my drive on number nine. My Pro-V1 appears to listen and the ball takes a nice hop off a mound in the fringe and kicks back into the fairway. I’ll have about 210 for my second into this par-5.

“Goddamn, A.J.,” Teddy says with a cough, as if I literally knocked the wind out of him. “Where’d a little thing like you learn to pound a ball that far?”

“My dad,” I say, casually bending down to pick up my tee.

“My dad taught

me

how to play, too,” Teddy says, “and I’ve been 30 yards shorter than you all day!”

me

how to play, too,” Teddy says, “and I’ve been 30 yards shorter than you all day!”

“Maybe you should hit from the ladies’ tees,” Governor Watson suggests wryly.

“Hell, no,” says Teddy. “If

she’s

hittin’ from the tips,

I’m

hittin’ from the tips.”

she’s

hittin’ from the tips,

I’m

hittin’ from the tips.”

“Well then, maybe your dad was just a lousy coach,” the governor deadpans, giving me a wink. Then he adds by rote, “Nice drive, Alexis. Excellent footwork.”

I nod to him as we hop in our separate carts—the governor and Teddy in one, me in the other, presumably so they can talk about me between shots. (I

am

technically here to talk about a job in the governor’s office.) But I don’t mind. Gives me time to focus on my game. Because if there’s anything I hate more than golf, it’s

losing

at golf.

am

technically here to talk about a job in the governor’s office.) But I don’t mind. Gives me time to focus on my game. Because if there’s anything I hate more than golf, it’s

losing

at golf.

I’m the oldest of four girls. When my youngest sister was born, I was seven; without missing a beat, my dad turned to me in the hospital and said, “Well—looks like

you’re

gonna be my golf buddy, kiddo.”

you’re

gonna be my golf buddy, kiddo.”

My father was an athlete back in the day—a star quarterback and pitcher, one of the few Jews at his high school to letter in both sports—but a torn rotator cuff his senior year forced him to quit and give up any dream (however improbable) of the NFL or the Major League. His freshman year at U Penn, however, his roommate introduced him to golf, where the essentially underhanded motion didn’t aggravate his shoulder. He was thrilled to discover a sport he could play without pain. And he didn’t realize how much he missed the competition (even if he was mostly competing against himself). So he plunged into the game wholeheartedly, his ambitions to be the next Sandy Koufax replaced by a drive to be the next Corey Pavin, the only Jewish golfer of note. But as quickly as he improved (breaking 80 after only two years!), breaking par proved tragically elusive. Then, during his senior year, just as the game was becoming more and more frustrating (my father told me later that he felt like he was actually getting worse) and he was giving up all hope of ever being happy doing

any

thing, David Benjamin Gould met Lisa Rose Bauman. And in quick succession they got married, had me, and my father went into the family business (a moving company called Gouldie’s). He hung up his ‘sticks’ for several years while he concentrated on being a good husband and providing for his new family.

any

thing, David Benjamin Gould met Lisa Rose Bauman. And in quick succession they got married, had me, and my father went into the family business (a moving company called Gouldie’s). He hung up his ‘sticks’ for several years while he concentrated on being a good husband and providing for his new family.

And he

loved

being a father. Loved showing me off to his friends and saying how proud he was of his little “bubbeleh-angel” (that was me). But he made no bones about also wanting a boy. He and my mother were young, he’d say. They were going to have

lots

of kids. And they did. But after Stephanie, then Robin, then Beth, my mother said

four is enough, oy gevalt

, and that’s when my dad transferred all of his pent up father-

son

energy to me. I was going to be the boy he never had.

loved

being a father. Loved showing me off to his friends and saying how proud he was of his little “bubbeleh-angel” (that was me). But he made no bones about also wanting a boy. He and my mother were young, he’d say. They were going to have

lots

of kids. And they did. But after Stephanie, then Robin, then Beth, my mother said

four is enough, oy gevalt

, and that’s when my dad transferred all of his pent up father-

son

energy to me. I was going to be the boy he never had.

He even joked about it openly. “This is my daughter, Alex,” he’d say, shortening Alexis to Alex (later shortened to A.J., which stuck). “The son I always wanted!” And the men at Shul would laugh and tug my cheek and I’d blush, trying to look sturdy and formidable. I guess my father thought it would lessen the sting if he admitted what he was really thinking. But it didn’t. It just made me want to please him even more. Made me want to be something I could never be: a boy.

So I played every sport possible in middle school. Field hockey, basketball, and lacrosse during the school year; golf and tennis over the summer. On Saturdays I took private tennis lessons at the club from a Canadian guy named Thierry who claimed to have been ranked as high as 164th on the ATP tour back in the 90s, though I was never able to confirm it. My father would sometimes watch from the miniature bleachers, sunglasses on, a furtive glance every few minutes toward the driving range across the parking lot where he’d rather be, but most of the time he spent Saturdays with my mom and my sisters.

That’s because Sunday was Daddy-A.J. day. We had a standing 3 p.m. tee time at Inverness Valley, one of the best munis in Connecticut. By then all of the old-lady foursomes were long gone, and the course was too hot for anyone else. We’d arrive ninety minutes early like tour pros. I’d spend twenty minutes stretching, thirty on my short game, thirty hitting balls, the final ten back on the putting green working exclusively on five-footers, and then straight to the first tee. And I loved every minute of it. Not because I loved the game so much—though I truly did enjoy it back then—but because it was time alone with my father.

On those Sunday afternoons, my dad never played. He didn’t carry my bag, either; that was my job, he said. But he walked the whole way with me. We’d talk about golf, of course, things to work on, options for the upcoming shot (he was the only golf coach I ever had). But we also talked about nothing. And everything. School and current events and movies and books. Even boys. We talked about things on the golf course that we’d never talk about at home or in front of mom. Somehow things said on those expansive swaths of green were permissible there and nowhere else. And from 3 pm until dusk every Sunday in July and August, I had my father all to myself. I didn’t have to share him with my sisters or my mom or anyone. It was Daddy-A.J. day. And it was sacred.

So I got good at golf. Very good. At 13, I quit all my other sports. At 15, I won a spot on the boys’ varsity team. At 16, I qualified for the U.S. Girls’ Junior Amateur. And then it got hard. And not fun. And my dad got hard. And not fun. And Sundays were no longer sacred. Even though I kept playing and kept winning, I learned to resent the game.

I could have gone to Duke (a respectable school, no doubt) on a golf scholarship, but I chose Princeton. Where I qualified for the newly established Kurland Scholarship. (Gouldie’s didn’t make my family wealthy.) My father couldn’t fault my choice, but he also made no effort to hide his disappointment. We talked less and less the next few years—a result of being away from home, of course, but it was also a self-imposed sentence. A break from the intense relationship we’d had throughout my high school years, which were marked by competition, success, and failure.

At Princeton, I threw myself into my studies. After excelling for so long at such a solitary and selfish sport, I wanted to do something meaningful with my life. I wanted to make a difference. So I decided to pursue a career in government.

With a double major in Poli Sci and U.S. History, I graduated Phi Beta Kappa in 2008 and went straight to D.C. where two summer internships on the Hill and my amazing college professor helped me secure a low-level job working for Congresswoman Fiona Clark (D-CT). She taught me that, as a woman in politics, I had to balance being cool and reserved with my usual kneejerk emotional responses. But I also had to make sure that I wasn’t being a pushover or a sycophant. In school, good grades and a strong work ethic got me respect. But in the working world—as a

woman

—I came to understand that wasn’t enough. “You have to

earn

respect,” Congresswoman Clark was fond of saying. “They won’t automatically give it to you, like they do with the boys.” So I had to fight a little harder to be treated as an intellectual equal. In doing so, I quickly made a name for myself as a smart, capable woman who could gossip with the boys and bullshit with the ladies. I had social media savvy, intuition about the younger electorate, I was Jewish, and female. (And kind of attractive, if I do say so myself. Whenever Facebook has “doppelgänger day,” I go with Amanda Peet for my profile pic.)

woman

—I came to understand that wasn’t enough. “You have to

earn

respect,” Congresswoman Clark was fond of saying. “They won’t automatically give it to you, like they do with the boys.” So I had to fight a little harder to be treated as an intellectual equal. In doing so, I quickly made a name for myself as a smart, capable woman who could gossip with the boys and bullshit with the ladies. I had social media savvy, intuition about the younger electorate, I was Jewish, and female. (And kind of attractive, if I do say so myself. Whenever Facebook has “doppelgänger day,” I go with Amanda Peet for my profile pic.)

After two years in the congresswoman’s office, I was a hot commodity. But I (wisely or unwisely) chose to

leave

Washington—and my very serious boyfriend—to be the deputy legislative council for Connecticut State Senator Iva Ellison Eisinger. It wasn’t necessarily a step

up

, but at 24, it was part of an impressive resume I was building

.

(Plus I wanted to be closer to home. I missed seeing my sisters. And—though I’m loathe to admit it—I missed my parents, too.)

leave

Washington—and my very serious boyfriend—to be the deputy legislative council for Connecticut State Senator Iva Ellison Eisinger. It wasn’t necessarily a step

up

, but at 24, it was part of an impressive resume I was building

.

(Plus I wanted to be closer to home. I missed seeing my sisters. And—though I’m loathe to admit it—I missed my parents, too.)

So for the past eighteen months, I’ve been enjoying my time with the state senator. But as anyone in politics will tell you, if you’re standing still, you’re going backwards. So I quietly put my name out there, and within forty-eight hours, Governor Watson’s office was calling for a meeting.

We’ve played eight holes so far and have yet to discuss anything of substance. I’m biding my time. It’s Governor Watson’s move to make. And though I won’t say relocating to Connecticut was a

calculated

move on my part, I’d be lying if I said being closer to the governor’s line of sight wasn’t also in the back of my mind when I left D.C.

calculated

move on my part, I’d be lying if I said being closer to the governor’s line of sight wasn’t also in the back of my mind when I left D.C.

Because Governor Charles Watson is the new rockstar of the Democratic Party: a man of the people who washes his beat-up Honda himself and still raises money from the one-percent. He’s equally at home shucking oysters in the harbor or sailing his 40-foot catamaran

around

the harbor. He’s got John Goodman’s easygoing approachability wrapped in George Clooney’s charm and boyish good looks. People are calling him the lost lovechild of Bill Clinton and J.F.K. Obviously those references aren’t lost on me. I’ve heard the infidelity rumors like everyone else, but I firmly believe all the talk about Governor Watson’s wandering eye is exaggerated. Stories strategically planted by the right to squash this star on the rise. (Seemingly the only way Republicans can denigrate these smart, charismatic, popular candidates is by painting them as immoral womanizers.) But seriously, who cares? In France they don’t give a

merde

what their leaders do in the bedroom. Why are we still such Puritans in this country?

around

the harbor. He’s got John Goodman’s easygoing approachability wrapped in George Clooney’s charm and boyish good looks. People are calling him the lost lovechild of Bill Clinton and J.F.K. Obviously those references aren’t lost on me. I’ve heard the infidelity rumors like everyone else, but I firmly believe all the talk about Governor Watson’s wandering eye is exaggerated. Stories strategically planted by the right to squash this star on the rise. (Seemingly the only way Republicans can denigrate these smart, charismatic, popular candidates is by painting them as immoral womanizers.) But seriously, who cares? In France they don’t give a

merde

what their leaders do in the bedroom. Why are we still such Puritans in this country?

They say it has to do with “character,” that a leader’s morality outside the office naturally translates to his integrity

inside.

But I maintain it’s about getting the job done. Tiger Woods is still the best golfer on the planet no matter what deviant sex acts he committed. And I think politics should be no different. It’s about getting the win, making lives better, and looking out for the people. If Governor Watson can raise the minimum wage and get the middle class back on track, so what if he’s grabbing a little action on the side? That’s between him and his wife (who’s super hot by the way—no way would anyone cheat on her!) I mean, George W. Bush may have kept his pants zipped, but I’ll take Clinton’s all-time high economic surplus over Bush’s two foreign wars and crippled economy any day.

inside.

But I maintain it’s about getting the job done. Tiger Woods is still the best golfer on the planet no matter what deviant sex acts he committed. And I think politics should be no different. It’s about getting the win, making lives better, and looking out for the people. If Governor Watson can raise the minimum wage and get the middle class back on track, so what if he’s grabbing a little action on the side? That’s between him and his wife (who’s super hot by the way—no way would anyone cheat on her!) I mean, George W. Bush may have kept his pants zipped, but I’ll take Clinton’s all-time high economic surplus over Bush’s two foreign wars and crippled economy any day.

Charles Watson is going places. And I want to align myself with his star and ride it all the way to the White House. There’s been talk about adding the three-term governor’s name to the DNC ticket in 2016: if Hillary runs, as her VP; if she doesn’t, well then…

“

That’s

the word, Chuckie. Or should I say…

Mister

President?”

That’s

the word, Chuckie. Or should I say…

Mister

President?”

As we drive down the fairway, I can hear Teddy going on about the increasing talk out of Washington. A few snatches of their conversation drift over our golf carts’ puttering engines.

“Knock it off, Teddy… nowhere

near

2016.”

near

2016.”

“…prime for it, Chuck… centrist Democrat… bringing Connecticut out of the Factory Dark Ages… mini-Tech boom… All you need now is….”

They finally stop and get out by Teddy’s ball in the rough. I park a few yards behind them (as is etiquette) and pretend to be engrossed in my scorecard.

“I’m telling you,” Teddy says, pulling a hybrid out of his bag, “everybody hated that little S.O.B. Then 9/11 comes along. Suddenly he’s the most beloved mayor in New York City

history

. He made a bid for the

White

House, for Christ’s sake! Now I’m not saying you want a terrorist attack on domestic soil. But a… I don’t know. A gas crisis. Or a natural disaster! Hell, look what Hurricane Sandy did for Chris Christie! Now that sack of potatoes is like the G.O.P.’s

golden

child!”

history

. He made a bid for the

White

House, for Christ’s sake! Now I’m not saying you want a terrorist attack on domestic soil. But a… I don’t know. A gas crisis. Or a natural disaster! Hell, look what Hurricane Sandy did for Chris Christie! Now that sack of potatoes is like the G.O.P.’s

golden

child!”

Governor Watson glances over to see if I’m listening. I can’t tell if he does or

doesn’t

want me to hear, so I keep drawing a “3” over and over on my scorecard with my mini pencil.

doesn’t

want me to hear, so I keep drawing a “3” over and over on my scorecard with my mini pencil.

“You need something like that,” Teddy continues. “Something that sucks for everyone so

you

can come to the rescue. You’ll be Bruce Wayne and Batman all rolled into one.”

you

can come to the rescue. You’ll be Bruce Wayne and Batman all rolled into one.”

“Bruce Wayne

was

Batman,” the governor points out. “They’re the same guy.”

was

Batman,” the governor points out. “They’re the same guy.”

“You can be friggin’ Deputy Dog, Chuck! You have something like 9/11 happen here while you’re governor? At the bare

min

imum, you’re in the number two spot on that 2016 ticket. Right, A.J.?”

min

imum, you’re in the number two spot on that 2016 ticket. Right, A.J.?”

Other books

Playboy Pilot by Penelope Ward, Vi Keeland

The Beginning of the End (Universe in Flames Book 4) by Christian Kallias

Welcome to the monkey house by Kurt Vonnegut

Captured Sun by Shari Richardson

Guilty Pleasure by Leigh, Lora

Silvertip (1942) by Brand, Max

Four Play by Maya Banks, Shayla Black

Heidi (I Dare You Book 1) by Jennifer Labelle

Nueva York: Hora Z by Craig DiLouie

Twilight of a Queen by Carroll, Susan