Phish (23 page)

Authors: Parke Puterbaugh

The year 1995 ended with what many fans consider Phish’s greatest tour (fall ’95), greatest month of touring (December ’95), and one of their greatest single shows (New Year’s Eve). The year 1996, by comparison, started out slowly and unfolded quite differently, because Phish needed time to work on a new album but also because they were beginning to feel a bit burned out.

The three-and-a-half-month trek that carried Phish through the end of 1995 had worn them out.

“At the end of our fall tour, there was this incredible feeling of having hit the wall,” Anastasio said. “Everybody was tired. I still thought we were playing well, but it was like a slow-burn kind of feeling just going to dinner with everybody every night. So much of what we do is about energy, and when people are feeling tired, it’s hard to put out that energy.”

Although 1995 ended with a lengthy tour, Phish actually didn’t play as many total gigs as they had in past years. In 1995, they played eighty-one shows—the least since 1987, when the band members were still in college or had jobs. In 1996, they played even fewer still (seventy-one shows in all). Almost every year until the breakup in 2004 yielded fewer Phish gigs than the previous one. By 1996, their priorities were changing, and they needed time off to catch their breath and reassess their position.

“It was like an era was coming to an end,” Anastasio said at the time. “We realized that we had to downsize, despite the fact we were growing in terms of numbers of people who were coming to see the band. We’d spread ourselves too thin. So we started cutting back.”

With the exceptions of an appearance at New Orleans’s Jazz and Heritage Festival and a one-off club show in Woodstock during sessions for

Billy Breathes

, Phish took a half-year break from live shows. They wouldn’t resume touring until July 1996, and even then they headed abroad for a one-month jaunt opening for Santana around Europe. America wouldn’t get a Phish tour until August, with the year nearly two-thirds over, which was unheard of.

Billy Breathes

, Phish took a half-year break from live shows. They wouldn’t resume touring until July 1996, and even then they headed abroad for a one-month jaunt opening for Santana around Europe. America wouldn’t get a Phish tour until August, with the year nearly two-thirds over, which was unheard of.

In April came the first side project that didn’t involve all four members of Phish. It was an avant-garde blowing session, called

Surrender to the Air

, that had been cut almost a year earlier. It was the product of two days’ worth of jam sessions involving a group of musicians handpicked by Anastasio. He claimed to have literally dreamt up the lineup of guitarist Marc Ribot; organist John Medeski; trumpeter Michael Ray, saxophonist Marshall Allen, and vibraphonist Damon R. Choice, all from Sun Ra’s jazz “Arkestra”; Jon Fishman and Bob Guillotti on drums; brothers Kofi and Oteil Burbridge on flute and bass; and trombonist James Harvey.

Surrender to the Air

, that had been cut almost a year earlier. It was the product of two days’ worth of jam sessions involving a group of musicians handpicked by Anastasio. He claimed to have literally dreamt up the lineup of guitarist Marc Ribot; organist John Medeski; trumpeter Michael Ray, saxophonist Marshall Allen, and vibraphonist Damon R. Choice, all from Sun Ra’s jazz “Arkestra”; Jon Fishman and Bob Guillotti on drums; brothers Kofi and Oteil Burbridge on flute and bass; and trombonist James Harvey.

In Anastasio’s recounting, “It was a big party with microphones on and tape machines running. It’s a pretty wild album. I wanted it to be symphonic in form yet jazz in language and thrash in energy.”

The participants in

Surrender to the Air

reconvened for two nights’ worth of live improv at New York’s Academy of Music—the last shows ever played at that venue. It was a cool idea to make an avant-garde side trip with such an impressive cavalcade of musicians, though maybe not the most listenable item in the vast catalog of Phish-related projects.

Surrender to the Air

reconvened for two nights’ worth of live improv at New York’s Academy of Music—the last shows ever played at that venue. It was a cool idea to make an avant-garde side trip with such an impressive cavalcade of musicians, though maybe not the most listenable item in the vast catalog of Phish-related projects.

Phish’s chief priority for much of 1996 was cutting a new album. Two years had passed since the sessions for their last studio album (

Hoist

), and while the assembly of their concert compendium,

A Live One

, had consumed comparable time and energy to a studio project, they were itching to lay down some new music.

Hoist

), and while the assembly of their concert compendium,

A Live One

, had consumed comparable time and energy to a studio project, they were itching to lay down some new music.

“Because the last one was live, it feels like we haven’t done an album since

Hoist

,” Anastasio said then. “And because of the whole way

Hoist

ended up going, it almost feels like we haven’t made an album since

Rift

. The focus for a long time has been on touring, and we haven’t been in the studio, so we’re chomping at the bit.”

Hoist

,” Anastasio said then. “And because of the whole way

Hoist

ended up going, it almost feels like we haven’t made an album since

Rift

. The focus for a long time has been on touring, and we haven’t been in the studio, so we’re chomping at the bit.”

In February 1996, Phish unplugged the phones and hibernated in a rustic barn-turned-studio next to a babbling brook in upstate New York, near Woodstock. They stayed there six weeks, working on material without a producer. The facility was called The Barn (not to be confused with Anastasio’s Barn Studio outside of Burlington. It was part of the Bearsville studio complex—a separate building that had been turned into a new recording space.

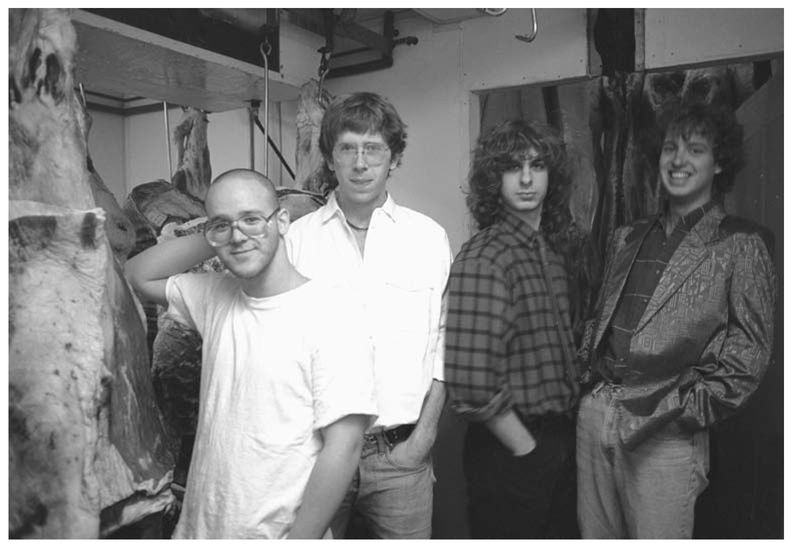

Meat Phish: Jon Fishman, Trey Anastasio, Mike Gordon, and Page McConnell in 1987

© PHISH, INC. 1987. COURTESY OF MIKE GORDON.

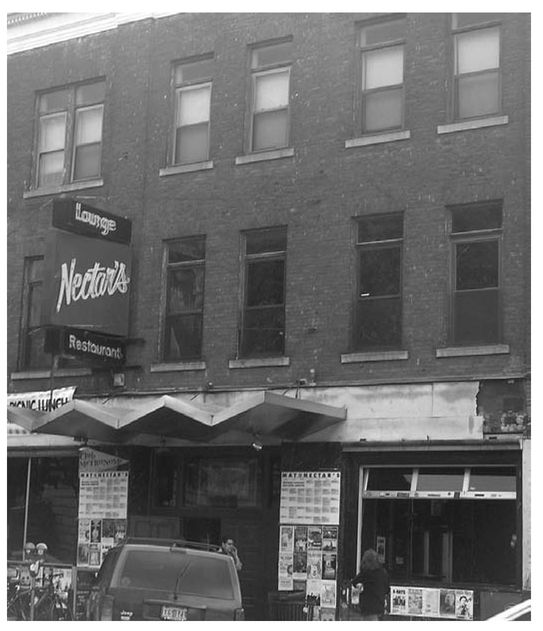

Nectar’s, the downtown Burlington club where Phish got their act together

PHOTO BY PARKE PUTERBAUGH.

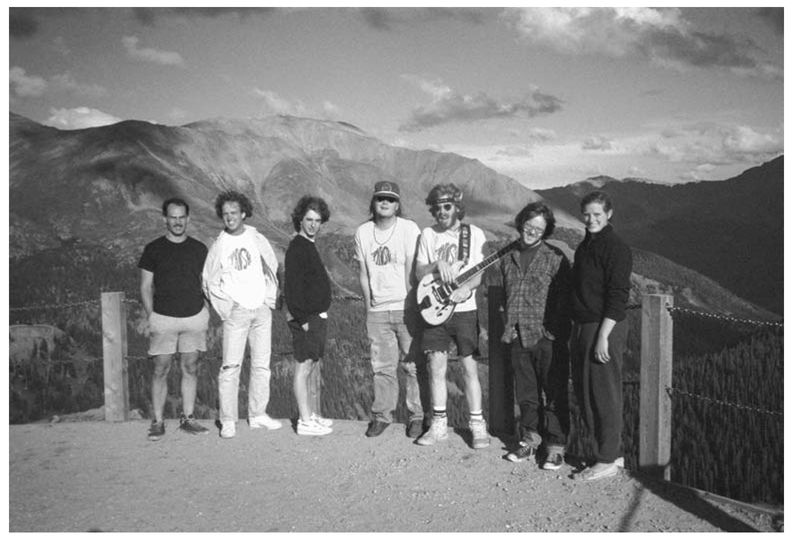

“Vermont’s most naive band” and crew en route to Colorado, 1988

© PHISH, INC. 1988. COURTESY OF MIKE GORDON.

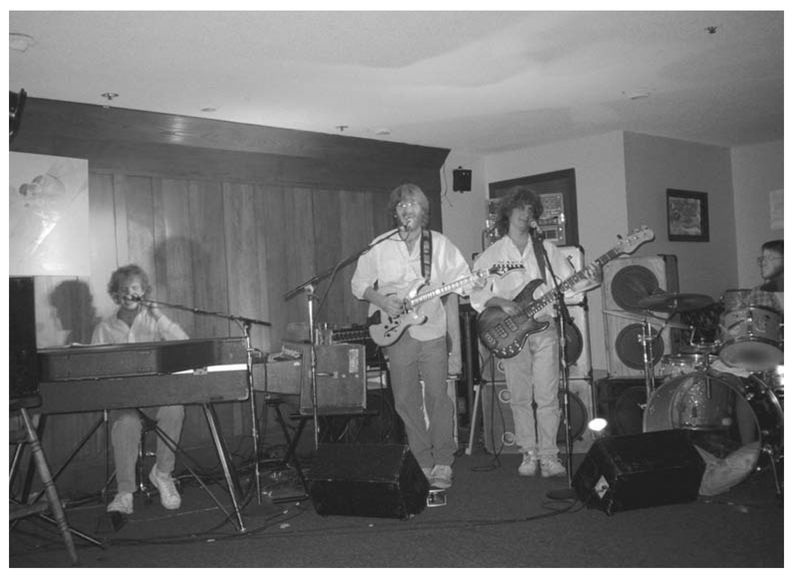

Rocking the Rockies: Phish play in Aspen

© PHISH, INC. 1988. COURTESY OF MIKE GORDON.

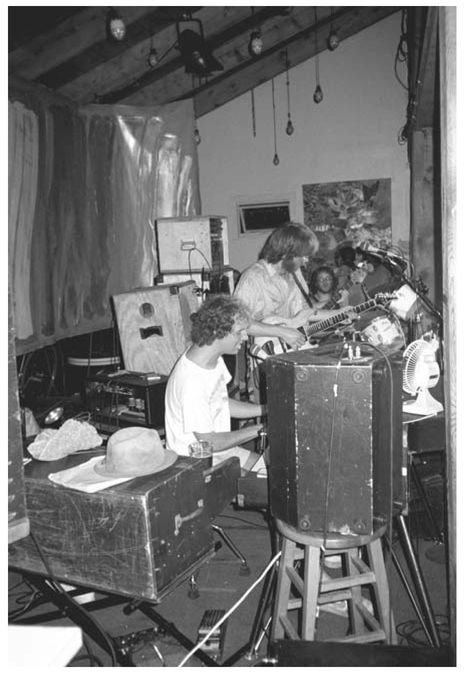

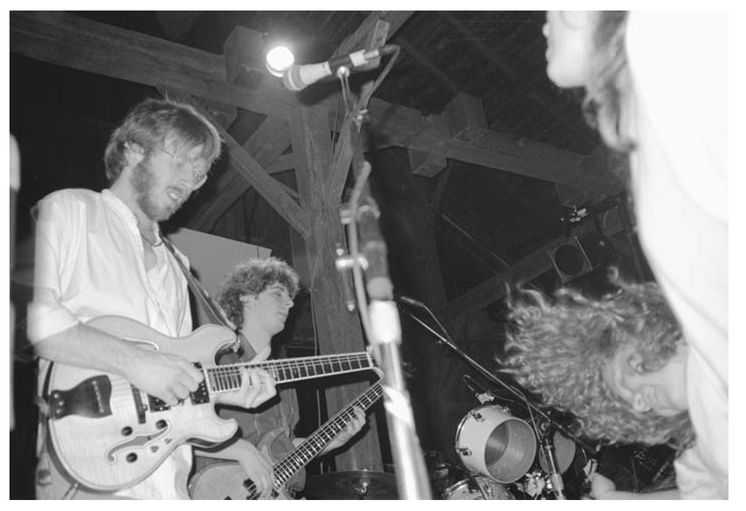

Nothing fancy: Phish at The Front, the next step up from Nectar’s

© PHISH, INC. 1988. COURTESY OF MIKE GORDON.

Band and fans are feeling it in Northampton, Mass.

© PHISH, INC. 1988. COURTESY OF MIKE GORDON.

The crowds are getting bigger: an outdoor gig in Townshend, Vt., 1990

© PHISH, INC. 1990. COURTESY OF MIKE GORDON.

The extended Phish family in the early nineties, with the band in the front row: McConnell (holding sign), Anastasio, Fishman, Gordon

© PHISH, INC. 1993. PHOTO BY ALLAN DINES.

Other books

Beautiful Disaster (A Pirate Romance book, Historical Romance) by Myers, Heather C.

Tom Swift and His Atomic Earth Blaster by Victor Appleton II

Death Comes To All (Book 1) by Travis Kerr

Serving Trouble by Sara Jane Stone

Lady in the Stray by Maggie MacKeever

Nothing but Trouble by Tory Richards

Alice in Virtuality by Turrell, Norman

A Healthy Homicide by Staci McLaughlin

America Aflame by David Goldfield