Phish (26 page)

Authors: Parke Puterbaugh

Lyricist Tom Marshall at the mysterious Rhombus, where he and Trey Anastasio wrote songs and partied as younger men PHOTO BY PARKE PUTERBAUGH.

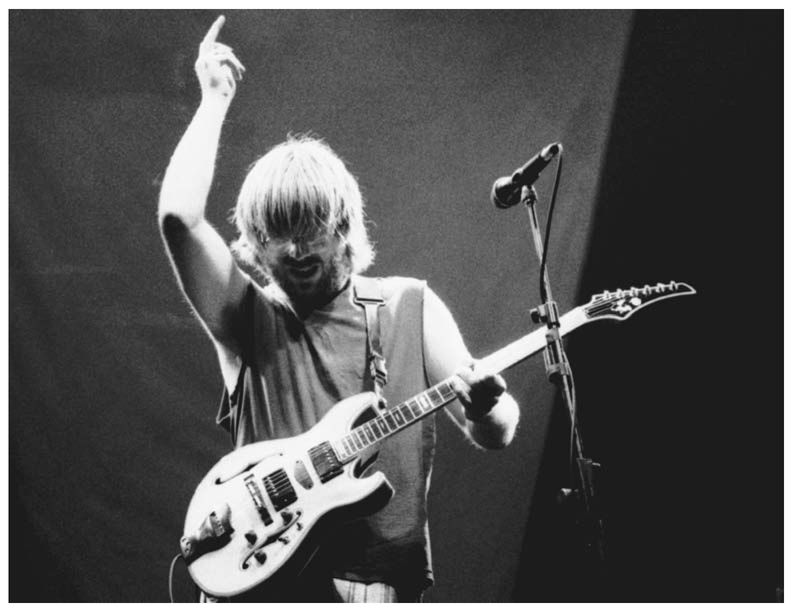

Trey Anastasio points the way forward

© PHISH, INC. 1994. PHOTO BY DAVE VANN.

“The idea was to scale back and start from ground zero,” Anastasio said. “With some of the other albums, I felt there were too many grandiose ideas. We were writing a lot of good music, but we tried to do too much. This time, all we wanted to do was get together and hang out. We didn’t have any plans. We weren’t talking much to anyone in management. It was just like, ‘We’re going into a barn; leave us alone.’”

The project began with “the blob.” The engineer cued up a reel of tape, and the band members picked straws to see who’d play the first note. Page McConnell drew the long straw. He hit a single note on the vibes. Anastasio tapped a steel drum. Fishman played something on the piano. Gordon plucked a bass note.

“We went around in a circle,” said McConnell, “playing one note at a time for about two weeks.”

The exercise evolved from single notes to a turn that might involve all of them jamming for five minutes or singing something or even erasing material. Gradually, Phish built up a “blob” of music whose freewheeling, democratic construction set the tone once the group moved to actual songs.

“We’d take the blob approach, trying to have fun with all of us contributing equally and feeling free to have a more open dialogue,” said McConnell. “It cleared our heads.”

What they cut once they got down to serious recording was promising but needed work. Some of the songs had already been successfully road-tested but sounded disappointingly flat in their studio incarnations. Their managers worried about how to broach this difficult matter with the band, but they came to the same conclusion on their own and decided to bring in an outside producer. They tapped Steve Lillywhite, who’d produced U2’s early work and, more recently, the Dave Matthews Band.

Lillywhite was an artist’s producer, and he excelled at sonic atmospherics. “He has a good sense of spatial relationships,” noted Anastasio. It was a good match, and with six more weeks of work in Woodstock that June,

Billy Breathes

became a stronger album.

Billy Breathes

became a stronger album.

The sessions retained their relaxed vibe. Turtle Creek flowed outside the barn where they were recording, and at quiet moments they could hear it gurgling while they were playing. Gordon drew a fascinating verbal portrait of the group’s unhurried daily routine:

“We’d arrive around 3 P.M., do ten takes of a song, take a dinner break around 6:30 and watch some TV, then do a bunch more takes of a song till about 1 A.M.,” he said. “It was okay because Steve Lillywhite was such a positive influence—dancing around and keeping our spirits up, which is his style. Then we’d take an hour and a half break to play ping-pong, hang out, or whatever, and resume around 2:30 or 3:00 A.M.

“By that time, I was usually laying on the couch, wondering when these guys are gonna give up. I’d get called to do a bass part, and by that time I’d be so tired that I’d just play my part without thinking too hard about it. Because we entered that subconscious zone where you’re not thinking or worrying but just playing, we captured some of our best takes in the early morning hours.”

Billy Breathes

is relatively understated by Phish’s standards, and it does exude a relaxed vibe that evokes the wee hours. Shortly before its release, Anastasio nodded along to a list of adjectives—calmer, subtler, less busy, Zen-like—that I used to describe it.

is relatively understated by Phish’s standards, and it does exude a relaxed vibe that evokes the wee hours. Shortly before its release, Anastasio nodded along to a list of adjectives—calmer, subtler, less busy, Zen-like—that I used to describe it.

“Like there was nothing left to prove?” he said, asking and answering his own question in a way that neatly summed up the album’s less-is-more aura and quiet confidence.

It was accorded a positive reception in the rock press without the usual cheap shots about the Grateful Dead and noodling. Even

Rolling Stone

gave it four stars (out of five), which amounted to a benediction of sorts.

Rolling Stone

gave it four stars (out of five), which amounted to a benediction of sorts.

“The album felt to me like what I had always ever really wanted, which was to hang out, stay up and record with those three guys in a

barn in the woods. The whole thing was like stepping backward or forward or something.”

barn in the woods. The whole thing was like stepping backward or forward or something.”

Anastasio was quick to note that Phish were not withdrawing but recharging. “The key is putting yourself in the right frame of mind and realizing what a great thing it is we get to do, which just opens everything up,” he said.

Gordon summed up Phish’s outlook like this: “We always have the attitude that each moment is the most important thing we’ve ever done. So we try to make it work and assume it can work, that there’s always that potential.”

Phish had been selling out almost everywhere they played. They were now hitting outdoor sheds in the warm-weather months and arenas in the winter. As far as record sales went, they were beginning to rack up some impressive numbers. Both

Hoist

and

A Live One

went gold, denoting sales of more than half a million copies.

Billy Breathes

entered

Billboard

’s album chart at No. 7—the highest position a Phish album has achieved to date.

Hoist

and

A Live One

went gold, denoting sales of more than half a million copies.

Billy Breathes

entered

Billboard

’s album chart at No. 7—the highest position a Phish album has achieved to date.

All the same, they still were not drawing attention in the entertainment press commensurate with their numbers and impact on the music scene. This situation both amused and frustrated the band members.

“It makes me laugh,” said Anastasio. “The media’s just completely missed the boat. We were chuckling about it after the Clifford Ball [their August 1996 festival]. Nobody from MTV News was there, and it was the biggest North American concert of the year. It was definitely groundbreaking. And regardless of the music, there was a real story that in an age of corporate sponsorship, this completely homegrown thing happened that was different than any other concert.”

The group’s low profile created a kind of paradox. By that time, nearly everyone had heard of Phish, but outside of the growing base of fanatics who followed the tours, relatively few had actually

heard

Phish. They were big but they were still kind of a mystery to mainstream music fans.

heard

Phish. They were big but they were still kind of a mystery to mainstream music fans.

“Sometimes I wonder,” Anastasio mused. “The media can’t claim any responsibility for making us what we are. So maybe they have nothing to gain from covering us at this point. Maybe it’s just a feeling of, ‘Whoa, we really missed it on that one . . . well, we’ll just talk about KISS.’ Know what I mean? I mean, how many magazines have had KISS on the cover?”

The Clifford Ball came after their month in Europe and a mere nine gigs (four of them at Red Rocks) on American soil during the first weeks of August. As an aside, Phish played one of the strangest and funniest sets of their career at the Melkweg, a music club and hash bar in Amsterdam. Between sets, they availed themselves of the fully legal smoking substances, and the ensuing high made hash of the second set.

“They all went to the side of the stage and puffed for an unbelievable amount of time, like a half-hour,” recounted Tom Marshall, “and then they went up and tried to play. They’d all try to start a song and go into a jam and then come out of the jam with another Phish song and go into another jam and then come out of the jam into another Phish song. They never went back and never had any idea where they were. The first set was coherent, but then they went into this wack thing. I loved it, it was great. The first time they ever came unrooted onstage,

ever

.”

ever

.”

Officially, the Clifford Ball drew a combined crowd of 135,000 over two days, making it the most highly attended concert event in North America of 1996. In

Pollstar

’s chart of the year’s top grossing touring acts, Phish placed eighteenth. That was impressive considering it was a light touring year for them and that their ticket prices were lower than those of the acts ahead of them.

Pollstar

’s chart of the year’s top grossing touring acts, Phish placed eighteenth. That was impressive considering it was a light touring year for them and that their ticket prices were lower than those of the acts ahead of them.

Planning for the Clifford Ball had taken months, and the issues at times seemed daunting. In fact, at the last minute, the festival almost didn’t happen. Promoter Dave Werlin had to pull a rabbit out of a hat to forestall cancellation by the Plattsburgh Area Revitalization Commission (PARC). Late in the game, the commission’s CEO called

to inform him they’d decided against hosting a concert/campout festival on their property, though they might reconsider for the following year.

to inform him they’d decided against hosting a concert/campout festival on their property, though they might reconsider for the following year.

“I decided to go for a Hail Mary pass and called the office of the state senator who represented the region. Although he was a Republican, he was also the chair of the New York State Finance Committee. We thought his office might understand the economic implications of tens of thousands of visitors coming to this depressed upstate community. Sure enough, his chief of staff heard us out. A couple of hours later, the PARC CEO called and asked if we could return to Plattsburgh to make another presentation, which we did, of course. And the rest is history.” Backstage at the Clifford Ball, the mayor of Plattsburgh—no doubt appreciating the boost that 70,000 visitors brought to the local economy—told McConnell, “You guys have got to come back next year!”

Indeed, though they never did return to Plattsburgh, the Clifford Ball would serve as the blueprint for a series of annual festival campouts in out-of-the-way places. What Phish did would inspire such multi-band rock festivals as Bonnaroo and Coachella. In fact, many of the staff and crew who worked on Phish’s festivals brought their expertise to those events and others like it. That the Clifford Ball succeeded beyond anyone’s expectations served as testimony to Phish’s visionary outlook and perseverance.

“I think there are solutions to all the logistical problems—any kind of problem—if you sit down and think about it long enough,” said Anastasio. “So many people are just naysayers. Take Plattsburgh. As soon as we started saying, ‘We’re going to do this concert in Plattsburgh . . . ’ ‘

Plattsburgh?!

That’s nearly in Canada. Nobody’s gonna go there. There’s nothing there, it’s this tiny little town. What are you, crazy? Let’s do it at Randall’s Island, then we’ll rake in the big bucks.’ That’s the general attitude:

Get the money

. You have to get away from that.”

Plattsburgh?!

That’s nearly in Canada. Nobody’s gonna go there. There’s nothing there, it’s this tiny little town. What are you, crazy? Let’s do it at Randall’s Island, then we’ll rake in the big bucks.’ That’s the general attitude:

Get the money

. You have to get away from that.”

With this, Anastasio summed up Phish’s philosophy: “Shut yourself off from the world, and just don’t listen to all the people who are going to tell you what you can’t do. Then just do it.”

SIX

Growing Pains: 1997-2000

D

uring the middle set on the final day of the Great Went—the second of Phish’s festival campouts, held the third weekend of August 1997—the band painted abstractly on pieces of wood that had been cut into artistic designs. Two by two they took turns painting while the others played music; fans called it the “Art Jam.” Throughout the weekend, Phish had solicited artwork from fans, which was collected and piled into a growing art tower. Now the musicians’ own contributions were assembled jigsaw puzzle-style into one big work that was passed by the crowd out to the art tower. It was hoisted to the top of the pile, crowning the collective creation.

uring the middle set on the final day of the Great Went—the second of Phish’s festival campouts, held the third weekend of August 1997—the band painted abstractly on pieces of wood that had been cut into artistic designs. Two by two they took turns painting while the others played music; fans called it the “Art Jam.” Throughout the weekend, Phish had solicited artwork from fans, which was collected and piled into a growing art tower. Now the musicians’ own contributions were assembled jigsaw puzzle-style into one big work that was passed by the crowd out to the art tower. It was hoisted to the top of the pile, crowning the collective creation.

Then, while encoring with “Tweezer Reprise,” it was all set ablaze with a giant match. The point of this act of immolation seems clear: live in the moment and don’t hold on to the past, because everything—art and music included—is fleeting.

Phish continued touring, albeit at a reduced clip, in the four-year period from late 1996 through 2000. Because their tours were briefer,

the special events assumed greater significance. New Year’s runs and Halloween shows remained annual highlights, and the group continued along the festival path they’d blazed with the Clifford Ball, staging the Great Went (1997), Lemonwheel (1998), Big Cypress (1999), and an unnamed 2000 campout in upstate New York informally dubbed “Camp Oswego.”

the special events assumed greater significance. New Year’s runs and Halloween shows remained annual highlights, and the group continued along the festival path they’d blazed with the Clifford Ball, staging the Great Went (1997), Lemonwheel (1998), Big Cypress (1999), and an unnamed 2000 campout in upstate New York informally dubbed “Camp Oswego.”

Then, in October 2000, they would embark upon a hiatus without specifying how long it might last (though there was little doubt they would eventually regroup). Despite all the positive spin put on the temporary breakup, it was a signal that things weren’t entirely copasetic in their world. In the years leading up to the hiatus, Phish’s figurative art tower started listing off-center.

Phish began to struggle with issues that included drugs, creative control, and the fiction of equal democracy. They changed their jamming style, moving in the direction of static, textural grooves that no one member might appear to dominate. Tom Marshall and Anastasio continued to generate the bulk of material, though there were semi-successful experiments in group writing in 1997 and 1998. During this period, Phish recorded a pair of albums whose differing constructions demonstrated opposite approaches to a long-simmering issue.

Story of the Ghost

(1998) bent over backward in the direction of full collaboration and group democracy, while

Farmhouse

(1999) reflected more of a unilateral vision from Anastasio. The stark differences in the assembly of those two albums was the most outwardly visible manifestation of growing pains a decade and a half into their career.

Story of the Ghost

(1998) bent over backward in the direction of full collaboration and group democracy, while

Farmhouse

(1999) reflected more of a unilateral vision from Anastasio. The stark differences in the assembly of those two albums was the most outwardly visible manifestation of growing pains a decade and a half into their career.

One can arguably divide Phish’s career into halves: B.C. and A.C. That’s before the Clifford Ball (B.C.) and after the Clifford Ball (A.C.). That August 1996 festival was a celebration and culmination of Phish’s age of innocence. The Clifford Ball was the last great hurrah for what longtime fans like to call the “old Phish.”

Other books

Sail of Stone by Åke Edwardson

Royal Sisters: The Story of the Daughters of James II by Jean Plaidy

The Best Australian Poems 2011 by John Tranter

Broken Arrow: A Military Erotic Romance by Fletcher, Kristin

Love's Hope (The Unknowns Motorcycle Club Book 2) by Reid, Ruby

Help Wanted by Meg Silver

The Quirk by Gordon Merrick

A Wicked Deed by Susanna Gregory

Deadly Arrival (Hardy Brothers Security Book 16) by Hart, Lily Harper

English Rider by Bonnie Bryant