Poison (19 page)

Authors: Jon Wells

The hard back of his thick hand smashed across the right side of her small, soft face. The force of the blow snapped her head around. Parvesh tasted her own blood on the inside of her lip, her cheek bone ached, a red welt forming, shooting pain up through her sinuses and head. Jodha continued yelling, but her hand was on the phone now. There had been other opportunities in the past

to report her husband. Two years earlier, on a February day in 1990, Parvesh went to the ER at St. Joseph’s Hospital. Jodha had hit her in the face and delivered a blow to her chest. Her face was sore and her head ached, along with her shoulder, and her chest felt crushed from within. The nurse X-rayed her and found part of a lung had collapsed. He had broken the seal covering the lung. The doctor asked how it happened, and Parvesh said Dhillon had kicked and punched her. But she would not call police, would not press charges. The assault wasn’t the first. There were two black eyes on separate occasions. She had gone to the family doctor for one of them and told him it was caused by a doorknob. It wasn’t time to tell the police. Still, as if sensing that proof might be needed some day, Parvesh had a friend take photos of her black eyes.

to report her husband. Two years earlier, on a February day in 1990, Parvesh went to the ER at St. Joseph’s Hospital. Jodha had hit her in the face and delivered a blow to her chest. Her face was sore and her head ached, along with her shoulder, and her chest felt crushed from within. The nurse X-rayed her and found part of a lung had collapsed. He had broken the seal covering the lung. The doctor asked how it happened, and Parvesh said Dhillon had kicked and punched her. But she would not call police, would not press charges. The assault wasn’t the first. There were two black eyes on separate occasions. She had gone to the family doctor for one of them and told him it was caused by a doorknob. It wasn’t time to tell the police. Still, as if sensing that proof might be needed some day, Parvesh had a friend take photos of her black eyes.

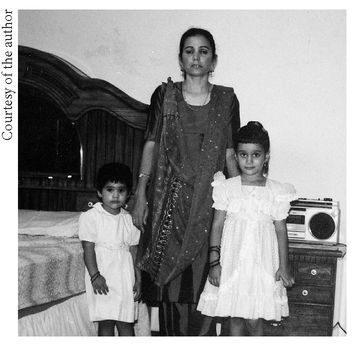

Parvesh and her girls

This time, the morning of August 14, would be different. The radio in the Hamilton police cruiser crackled. Doug Rees and Rick Abelson had just come on duty. “Domestic,” the voice said. “Three-six-two Berkindale Drive.” Rees wheeled the car around. They pulled up in front of the house. A knock on the door. Parvesh answered, Dhillon was in the basement. She told her story in English, opened her mouth to show the cut. Rees and Abelson went downstairs.

“So what happened here this morning?” Rees said to Dhillon. Dhillon’s face showed no emotion. No yelling, no exaggerated movements. He was calm. His English, while broken, was easily understood.

“Hardev does nothing around here.”

Rees, a 10-year veteran, put his hand around Dhillon’s arm.

“You are under arrest, sir. Will you please follow me to the car?”

Rees waited for a reaction. He always gave them a choice. You can come outside and struggle, be cuffed, humiliated for neighbors to see, or you can leave like a gentleman. Dhillon, despite his size and his attempts to portray himself as an unhinged tough guy to friends, never physically challenged Hamilton police officers. He walked to the car quietly, with Rees guiding him by the arm. He rode in the back seat of the cruiser, saying nothing.

Rees stopped at the Stoney Creek station to write the report while Abelson took Dhillon to the downtown police station. The charge was Level One assault. He spent the day in a cell, then was shackled and driven to the court on Main Street. He was released on bail. Parvesh testified against him. He was convicted and fined.

“What happened, Jodha?” one of his friends asked him later.

“Three hundred dollars,” Dhillon said, his face placid, as though discussing the weather. “Family problem.”

CHAPTER 10

GOD’S WILL

Warren Korol checked out an unmarked white Crown Victoria from the carpool at Central Station and drove to Hamilton General Hospital. He had an appointment with forensic pathologist Dr. David King, the one who had performed the postmortem on Parvesh Dhillon. They now had proof that Ranjit had been killed by strychnine. But proving Parvesh had met the same fate was a much greater challenge.

King, when consulted on reopening the investigation into her death, had an idea. Parvesh had been dead 19 months now, but he had filed away a box of Parvesh’s tissue samples sealed in wax in the storage room. Minute quantities of poison in her system could have already disappeared with time, or been eliminated when the samples were sliced and packed in wax at the autopsy. But it was worth a shot. He walked to the storage room, just around the corner from his office in the forensic pathology department, the smell of formaldehyde present as always. He had a staffer take photos of him at every step. The box was still there. Inside were 32 square blue-gray plastic cartridges, each about the size of a watch face, each containing a tiny piece of Parvesh’s organ tissue sealed in wax. King wrapped tape around the box.

Parvesh’s tissue samples were stored in cartridges like these.

Korol greeted King, who handed over the box. Then Korol was back in the car, the box on the seat beside him, on the QEW bound for Toronto, driving in silence, thinking about the case. The Crown Vic descended from the Gardiner Expressway. Korol drove up Bay Street and parked next to the undistinguished building of dirty gray concrete and brown brick, two flags snapping high atop poles outside. He entered the George Drew Building, which housed

the Centre of Forensic Sciences. He signed in on the second floor, then delivered the box to the lab.

the Centre of Forensic Sciences. He signed in on the second floor, then delivered the box to the lab.

Korol next headed to east Hamilton with his partner, an officer named Billy Paynter, and parked at Ranjit Khela’s house on Gainsborough Road. His family still lived there, including those who had clustered around him crying the night he died. Korol knocked on the door. Paviter Khela, Ranjit’s uncle, answered. He said nothing and let the detectives in. Sitting inside was Lakhwinder Sekhon, Ranjit’s widow.

“I am Detective Sergeant Warren Korol and I am investigating the death of Ranjit Khela.”

The family stared blankly at him. Paviter said something in Punjabi. Now Korol returned the stare with one of his own. What the hell were they saying? Korol had hoped they would know a bit of English. The visit was over. The cold case was difficult enough, but Korol couldn’t even communicate with witnesses. It wasn’t just the language barrier. There was a cultural divide, too. Even some members of Hamilton’s growing Indian community who spoke English were reluctant to talk to two white cops. It was their protective mechanism, a shield when feeling threatened by a cop, a journalist, a stranger.

No speak English

. Korol needed help or the case of his career was finished.

No speak English

. Korol needed help or the case of his career was finished.

The rookie’s dark eyes narrowed and focused, trying to interpret the movement of the silhouettes in the back windshield of the idling car. He walked slowly toward the vehicle.

It was May 1, 1989. Kevin Dhinsa had joined the Hamilton police force less than a year earlier. Now he had pulled over a car that had run a stoplight on Bay Street. Dhinsa checked the plate, ran the number on the computer of his cruiser. Stolen car. He made quick mental notes as he drew closer. Two occupants in vehicle. Appear to be male. Movement? No—yes. Yes, one of them reaching behind the seat.

The pale brown skin tightened on Dhinsa’s face, his heart beat faster. Right hand on the grooved plastic grip of the Glock, out

of the holster, pointing the muzzle at the ground. He was almost even with the car. The rest happened so fast. Suddenly the vehicle was moving, right back on top of him, on an angle. He reacted. Dodge, turn, raise the Glock, fire, an explosion, rear tire blown. But one shattered tire wasn’t enough. The driver hit the gas and took off. Dhinsa had slowed him down, however, and other cops made the collar a few blocks away. Commendation? No. Instead the rookie had to defend himself against a charge under the Police Act because he had pulled his gun in public. A few days earlier, a Toronto cop had shot a young man by mistake. Police brass across Ontario were on edge. If he was found guilty, Dhinsa was off the force. That possibility made him think of his parents, Sawaran and Ajit. They would be so upset.

of the holster, pointing the muzzle at the ground. He was almost even with the car. The rest happened so fast. Suddenly the vehicle was moving, right back on top of him, on an angle. He reacted. Dodge, turn, raise the Glock, fire, an explosion, rear tire blown. But one shattered tire wasn’t enough. The driver hit the gas and took off. Dhinsa had slowed him down, however, and other cops made the collar a few blocks away. Commendation? No. Instead the rookie had to defend himself against a charge under the Police Act because he had pulled his gun in public. A few days earlier, a Toronto cop had shot a young man by mistake. Police brass across Ontario were on edge. If he was found guilty, Dhinsa was off the force. That possibility made him think of his parents, Sawaran and Ajit. They would be so upset.

His family had moved from India to Hamilton in 1976. Dhinsa’s grandfather had been the deputy fire chief in Bombay. Growing up, his family moved frequently because his father was a civil engineer who worked for a university that regularly relocated him. Kevin came to Canada at 15. Back then he still used his Sikh first name, Kamaljit. When he was in his early twenties in Hamilton, before his life as a cop, an Irish boss he worked for anglicized his name and Dhinsa eagerly adopted it. He worked at his English, so much so that he lost nearly any trace of an Indian accent, speaking in a perfect, measured baritone. In Hamilton, his parents were so proud he was a police officer. Kevin Dhinsa, in the eyes of his family and the local Indian community, had made it.

In the end he was found innocent of any wrongdoing in the tire shooting incident. A rough ride for the rookie, but it did not inhibit his brashness on the job. There was also the case where he was alone on foot patrol, took on four young men he suspected of drug dealing on the street, grappled with one of them, and they both plunged through a plate-glass window. Dhinsa got to his feet and saw the other man down, lying on shattered glass—and a perfectly clean gash in the man’s neck, blood pumping out rhythmically. Dhinsa’s chest went hollow, his breath gone. Had he just killed an unarmed man? While executing a simple drug arrest? Police investigated the incident internally, Dhinsa’s career on the line again. Again he was found innocent. And the injured man lived.

One day in 1988, Dhinsa, a rookie in uniform, rode an elevator up a city building with his training officer. A woman in the elevator whispered to her child, “Behave yourself or the policeman will take you away.” It was a joke. Dhinsa said nothing. The training officer, whose face usually bore a mirthful look, wheeled around, serious.

“Listen, I don’t appreciate that,” he said. “That’s not a nice thing to say to a child. We are police officers, we’re his friends. Don’t scare him like that.”

The officer was Warren Korol. Korol and Dhinsa went their separate ways. They were reunited in the fall of 1996. At that time Dhinsa worked in vice and drugs. He was seconded out of the branch to assist lead investigator Korol in the possible double-homicide case. Dhinsa, a Sikh, fluent in Punjabi, was the logical choice. Korol and Dhinsa now embarked on the case of their lives, one of the most expensive and complicated homicide investigations in Canadian history, one that one day would even make headlines back in Kevin Dhinsa’s home country.

Kevin Dhinsa

Other books

A Bend in the River of Life by Budh Aditya Roy

The Pirates of Sufiro (Book 1) (Old Star New Earth) by Summers, David Lee

Heartbeat by Faith Sullivan

Vampire - In the Beginning (Vampire Series Book 1) by Mitchell, Charmain Marie

Lost Time by Ilsa J. Bick

Mad Scientists' Club by Bertrand R. Brinley, Charles Geer

The First Annual Grand Prairie Rabbit Festival by Ken Wheaton

Drive to the East by Harry Turtledove

Jack by Daudet, Alphonse

Strong and Stubborn by Kelly Eileen Hake