Poison (16 page)

Authors: Jon Wells

“If I ever get out,” Collier hissed at McCulloch, “I’m comin’ back here. And you’re a dead man.” At the criminal trial, the jury read its verdict and Collier, enraged, jumped out of the prisoner’s box, hit a court officer, and lunged at McCulloch, spitting invective. The Scot had stayed put in his chair, unblinking.

“Oh,” he said, his Scottish brogue rolling over the hard consonants, “he did not like Sergeant McCulloch one bit.”

McCulloch was now 57. The moment he picked up the phone that Tuesday morning, a faint light finally shone on the trail of the serial killer. This fella, McCulloch reflected, was an original. “Just about slipped through the cracks, too.”

The caller was not a cop or a medical official or a relative of one of the victims. But McCulloch used his horse sense, believed what he heard. And he acted. Dave McCulloch was the first police officer to get involved. He phoned the forensic pathology department at Hamilton General Hospital. Later, he walked into the office of Hamilton police inspector Bruce Elwood. “Bruce, I think we might have ourselves a double homicide here.”

It seemed like an end, of sorts. In fact it was just the beginning, because Sergeant McCulloch would be well into retirement, his old billy club a decoration in his basement den, before much of anything was resolved.

Cliff Elliot never worked Fridays, not anymore. That was for junior claims investigators. But, for some reason, he had worked on Friday, August 2, 1996. Shirley, his assistant, put the fax on his desk early that morning before he arrived at the office on Main Street West. It was from Metropolitan Life Insurance, asking for documents regarding a claim for the death of a man named Ranjit Khela. Elliot read the details in the fax. Deceased’s date of birth: January 1, 1971. Village of Mau Sahib, District of Jalandhar, Punjab. That made him about 25.

Young, thought Elliot. Had to be a sudden death, some kind of accident. Auto, probably. The reporting coroner was Dr. Bashir Khambalia, a family physician. As a matter of protocol, Elliot needed to call the coroner for more information. Khambalia was not available. Elliot, as usual, was not going to wait around. He left his office. The fax said Ranjit’s insurance policy had come into effect on June 18, 1996. The date of his death was June 23, 1996. He dies five days after the policy was taken out? Elliott drove to the downtown public library, flipped through back issues of

The Hamilton Spectator

,

The Toronto Star

, and

The Toronto Sun

to see if there had been any recent coverage of a young East Indian man’s sudden death in east Hamilton. Nothing. It was now 3 p.m., a long weekend looming, but Elliot returned to the office. He phoned the beneficiary listed on the fax. Fellow named Sukhwinder Singh Dhillon. Relation to deceased: uncle. A woman answered the phone and said Dhillon wasn’t due home until later.

The Hamilton Spectator

,

The Toronto Star

, and

The Toronto Sun

to see if there had been any recent coverage of a young East Indian man’s sudden death in east Hamilton. Nothing. It was now 3 p.m., a long weekend looming, but Elliot returned to the office. He phoned the beneficiary listed on the fax. Fellow named Sukhwinder Singh Dhillon. Relation to deceased: uncle. A woman answered the phone and said Dhillon wasn’t due home until later.

“I’ll call back,” Elliot said. He phoned the next week, on Wednesday, August 7. He got Dhillon on the phone, introduced himself. “Mr. Dhillon, what was your relationship to the deceased?” Elliot asked.

“I am his uncle,” Dhillon said.

“I will need some signed authorizations to get medical records and so on that will be needed in order to process the claim,” Elliot said.

“Okay.”

Dhillon agreed to meet on Monday, August 12 at 10 a.m. It was hot and muggy that morning. The air trapped over the lower city felt like a warm wet rag over the mouth. Cliff Elliot didn’t know it, but he was about to meet Sukhwinder Dhillon for the second time. He drove to the house on Berkindale Drive.

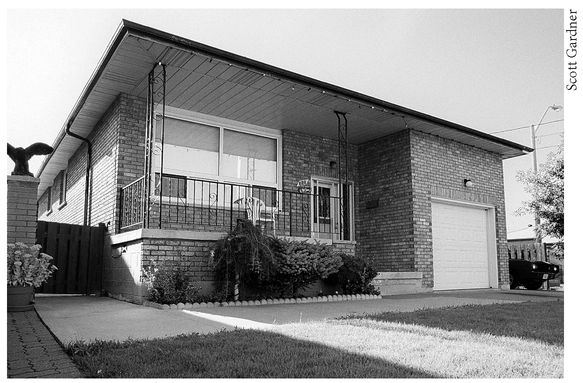

Dhillon’s house on Berkindale Drive in east Hamilton

Next door was Olga Vidal’s place, Parvesh Dhillon’s old friend. The Vidals were originally from Portugal. A few years back, they had placed two small statues out front, one of a lion, the other of an eagle. And they hung a tiled plaque on the front brick wall, a depiction of Christ. An inscription on it, in Portuguese, translated as “God of miracles.” On a nondescript suburban street like Berkindale, the place stood out. To someone like Cliff Elliot, it was unforgettable. He pulled his Tempo in front of Dhillon’s house, but there was the fire hydrant. Elliot, the straight arrow, pulled ahead in front of the house. It all seemed so familiar.

I’ve been here before, he thought. But with so many cases and contacts filling his head, it was hard to say when. Dhillon greeted Elliot at the door. They spoke in the basement, filled out forms, Elliot asking questions.

“How did your nephew die?” Elliot asked.

“Ranna was watching TV, said he had a pain in his chest, then fell to the ground and died in the hospital. That was it.”

Elliot stared at Dhillon. The nonplussed attitude—he’d seen that before, too.

“Yes. Well, did the police or coroner get involved?”

“I don’t know,” Dhillon said.

“I need to contact the closest next of kin for Mr. Khela.”

“That’s me. I am his uncle.”

“Where are Mr. Khela’s parents?” Elliot asked.

The Khelas had arrived in Hamilton shortly after Ranjit’s death, and since then Dhillon had seen them frequently. They were staying on Gainsborough Road, minutes from Dhillon’s home.

“They live in India.”

Elliot continued. “Some medical institutions won’t accept just your signature on the forms. I need an address for Mr. Khela’s parents.”

“I think they’re traveling in the United States somewhere, or B.C.,” he said. “I could have them come to Hamilton.”

“What about Mr. Khela’s wife?”

“Nobody knows where she is.”

Elliot tried to determine how well he understood English vernacular. “Can I see some ID?” he asked, using the acronym on purpose. Dhillon quickly produced his driver’s license number, then his social insurance card. Elliot copied the numbers in his book. Elliot asked to see some of Ranjit’s documents that Dhillon had in hand, including Ranjit’s driver’s license.

“Mr. Dhillon, the insurance claim says Ranjit lived at your address, 362 Berkindale. But Ranjit’s driver’s license says his address is 188 Gainsborough.”

“My brother lives at 188,” Dhillon said. “Ranna spent time at each house, he just used 188 for his records.”

“I will try to get the information that Met Life needs from the doctors and hospitals,” Elliot concluded, “but I have to tell you there is usually a hiccup. I still need to get signatures from his parents, whenever they arrive.”

Elliot left the house, looked once more at Dhillon’s house, and the Vidals’ next door. Back at the office, he asked around. Khela? Ranjit Khela? Anyone hear that name before? No. Elliot shuffled to the filing cabinet. Under K, nothing. No Khela. Well. What about the beneficiary, Mr. Dhillon? There were several Dhillon files. But just one with the address where Elliot had just been: 362 Berkindale: Dhillon, Parvesh Kaur. Born in Punjab, July 15, 1958. Died on February 3, 1995, in Hamilton. Life insurance policy beneficiary: Sukhwinder Dhillon. Husband. It was the file Elliot

himself had put away the year before. Holy mackerel, thought the Velvet Hammer. He sat at his desk and read the file more closely, then looked over at his secretary.

himself had put away the year before. Holy mackerel, thought the Velvet Hammer. He sat at his desk and read the file more closely, then looked over at his secretary.

“Shirley, there’s something not right here. Two young people with the same beneficiary—one was his wife and one was his nephew, apparently. Both died suddenly, no cause for either.”

Elliot wound back the tape in his mind. Parvesh. Mr. Dhillon’s nonchalant reaction when they discussed her death. Now he remembered.

“Honey,” he said to his wife, Amelia, as he came through the door at home that night, “I had the biggest case of déja vu today.”

Cliff Elliot thought of nothing else that evening. First thing the next morning, Tuesday, August 13, he was on the phone with Dave McCulloch. “Sergeant, I’ve got some information I think you should know about.”

That afternoon, McCulloch visited forensic pathology in the basement of Hamilton General Hospital. He met with forensic pathologist Dr. Chitra Rao. She listened to McCulloch relay details and speculation passed to him by Cliff Elliot. Two sudden deaths. Two healthy, relatively young adults. Both from India. Unknown cause of death. One insurance beneficiary. Rao retrieved the files on Parvesh and Ranjit. She noted that the postmortem report for Ranjit was not yet finished by Dr. Chris Clague, a medical pathologist who had conducted Ranjit’s autopsy because he was on call helping out the forensic pathologists, Rao and Dr. David King. Clague was a Brit who had lived for several years in Canada but would soon be returning to the United Kingdom to work at the Isle of Man hospital. So far Clague had hypothesized noncriminal drug poisoning or perhaps infection. As a matter of course, Ranjit’s tissue and blood samples were kept for further study. The coroner who handled Ranjit’s death, Dr. Bashir Khambalia, did not order advanced toxicology. He was not required to do so.

Chitra Rao was from a town in India called Kerala. Her father had died before her second birthday, and she was sent to live with a guardian in Sri Lanka. She was thoroughly acquainted with the dark side of human nature. Young Chitra had hungrily observed her guardian’s career as a criminal lawyer. At 10 years

old she sat at the kitchen table with him as he talked about cases, let her read his papers. He hoped she’d be a lawyer. Instead Chitra went to medical school in Bihar, in northern India, with an eye toward forensic pathology. As an intern, she became well versed in criminal poisoning, saw cases frequently in the hospital, victims of poisoning from chloroform, arsenic—all substances that were readily available. Later, she became a devotee of forensic mystery writer Patricia Cornwell, even striking up a friendship with her. Back in 1983 Rao solved the murder of McMaster University professor Edith Wightman. The professor was found dead in her office, a white towel stuffed in her mouth. No sign of a struggle, Rao noticed. Curious, she thought.

old she sat at the kitchen table with him as he talked about cases, let her read his papers. He hoped she’d be a lawyer. Instead Chitra went to medical school in Bihar, in northern India, with an eye toward forensic pathology. As an intern, she became well versed in criminal poisoning, saw cases frequently in the hospital, victims of poisoning from chloroform, arsenic—all substances that were readily available. Later, she became a devotee of forensic mystery writer Patricia Cornwell, even striking up a friendship with her. Back in 1983 Rao solved the murder of McMaster University professor Edith Wightman. The professor was found dead in her office, a white towel stuffed in her mouth. No sign of a struggle, Rao noticed. Curious, she thought.

She had turned to a Hamilton cop and said, “What about chloroform?”

Dr. Chitra Rao, forensic pathologist

The cop smiled. Chloroform? Who uses chloroform these days? Rao sent the towel to the Centre of Forensic Sciences in Toronto for testing. Chloroform. That’s how Wightman had been subdued before she was robbed, then suffocated on the towel. The killer was eventually caught. Case closed.

She listened to McCulloch’s story. Two sudden deaths in the Indian community. Coincidence? Natural causes, though unexplainable? Instinctively, darkly, Rao thought poison. She phoned CFS. She was sending samples from Ranjit Khela’s tissue and blood for a tox screen. In 1996, the CFS general drug screen could detect

only a handful of poisons. But Rao wasn’t fishing. She knew she was looking for murder and was already speculating on the weapon. She told a CFS toxicologist to narrow the scope of the screen.

only a handful of poisons. But Rao wasn’t fishing. She knew she was looking for murder and was already speculating on the weapon. She told a CFS toxicologist to narrow the scope of the screen.

“Check for chloroform,” she said on the phone. “And strychnine.”

Other books

Plastic by Christopher Fowler

Forbidden Pleasure by Lora Leigh

Wanted Dead by Kenneth Cook

The Rogue by Janet Dailey

NaGeira by Paul Butler

call of night: beyond the dark by lucretia richmond

For The Death Of Me by Jardine, Quintin

Shadow Light (Beautiful Beings #3) by Gow, Kailin

The Collective by Hillard, Kenan

The Unfortunate Traveller and Other Works by Thomas Nashe