Poison (13 page)

Authors: Jon Wells

Back in Ludhiana, Dhillon drove Kushpreet from his house to her uncle’s place across town, her Uncle Jagdev and Aunt Iqbal Mundi. He needed to talk privately to his niece, Sarvjit, who was 20 years old. Dhillon knew that Sarvjit might one day join him in Canada to help look after Harpreet and Aman, his daughters by Parvesh. She should know the truth. She might hear vicious rumors about him. He told her that Sarabjit’s babies had not been his.

“

Bholi

,” Dhillon said, using Sarvjit’s nickname. “You should know that Sarabjit was pregnant before I met her. It’s not right, you know that. I’m divorcing her, and her parents say it’s fine, to go ahead with it. They understand.” Sarvjit listened. Dhillon

continued, “The twins, babies, they weren’t mine. But they are spreading rumors about me. Don’t believe them, Bholi.”

Bholi

,” Dhillon said, using Sarvjit’s nickname. “You should know that Sarabjit was pregnant before I met her. It’s not right, you know that. I’m divorcing her, and her parents say it’s fine, to go ahead with it. They understand.” Sarvjit listened. Dhillon

continued, “The twins, babies, they weren’t mine. But they are spreading rumors about me. Don’t believe them, Bholi.”

It was about 8 p.m. on Monday, January 22, when Dhillon arrived at Uncle Jagdev’s house in Ludhiana to pick up Kushpreet and return her to her parents in Tibba. They had been pressing him hard about getting Kushpreet into Canada. He said he would take her the next day for the required physical examination. In the car, Dhillon talked to Kushpreet once more about the special pill he had from Canada. The pill will hide the pregnancy. It might be the only thing that gets you to Canada. We all want to make sure you get to Canada. I do, your parents do. Please, take it.

They arrived in Tibba at 10 p.m. Dhillon pulled the Maruti in front of her family’s tiny home. Kushpreet got out of the car. Was Dhillon coming in? “I can’t stay,” Dhillon said. “Business in Chandigarh early in the morning. I’ll be back tomorrow afternoon to take you for your physical.”

The next day Kushpreet was preparing lunch in anticipation of Dhillon’s return. She had to stop. Suddenly she was not feeling well. Her skin tingled, as though a rash had developed. She took a bath. It didn’t help. The water seemed to singe her skin. She dried off. It felt as if she couldn’t breathe. She sat in the kitchen next to her younger sister, Sukie. “I don’t feel well,” Kushpreet said. “And look at my feet.” The skin looked blue. What was going on? Kushpreet was healthy. She couldn’t recall the last time she had been to a doctor. Sukie helped her out of the kitchen into the small courtyard. Kushpreet lay on a cot. Sukie noticed the spots on her sister’s skin.

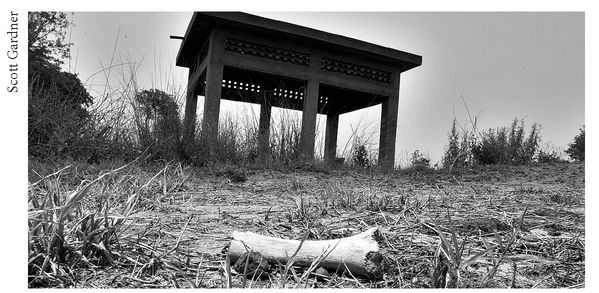

The courtyard where Kushpreet fell ill.

“Something strange is happening to me,” Kushpreet said, starting to moan. “What

is happening? She grew tense, stiff. “Can you get me some water?” Her mother came to sit with her. Did she eat something?

is happening? She grew tense, stiff. “Can you get me some water?” Her mother came to sit with her. Did she eat something?

“No,” she replied. “But I took a pill.” Then her speech slurred, her mouth clamped itself shut, her lips curled back into a grimace. She looked at her sister, Sukie, pointed her finger to her mouth. “Medicine,” she moaned. “Jodha.”

“We’ll get you to the hospital,” Sukie said. She ran out of the courtyard, up the narrow brick alleyway to summon Pargat, their tall, strong cousin. Pargat ran with Sukie to the house and found Kushpreet on the ground, her body rigid. For a brief moment, the convulsions stopped. Kushpreet could speak. “I don’t know what is happening,” she managed to say. “I think—I think I’m dying. I can’t feel my legs. I’m gone. Quickly, take me quickly. I’m dying.”

The village doctor arrived. He could do nothing. Take her to the hospital, he said. Few people in Tibba, a village of 1,200, owned a car. Pargat scooped up his suffering cousin in his arms, her back arched, face twitching. He carried her up the narrow street, then got on his tractor with her and drove to the end of the road, waiting for the car that had been summoned. Family members loaded Kushpreet into a tiny Fiat, her rigid legs sticking out the back window. Her body again shook violently. Family wept at the sight. Kushpreet urinated in the car. They drove to Bhambri Hospital. The one-storey, weathered, flesh-colored, concrete building was 20 minutes away along the rough country roads. It was named after the doctor who owned it, Dr. Mohinder Bhambri. In the car, the convulsions eased again. Kushpreet fought to speak, slurring her words.

“Mother,” she said. “The medicine. I took the medicine. Jodha.”

By the time they got Kushpreet to the hospital, she was unconscious. The doctor who checked her asked what she ate. Nothing, said the family.

“Take her home, unless you want to get the police involved,” the doctor said.

It was not an unusual piece of advice in Punjab. When police officers are called to an emergency, victims often have to pay for their services. So Kushpreet’s family took her away in the car. There

was no further examination. The stiffness had gone, her body now limp. She was dead. There would be no autopsy, no investigation.

was no further examination. The stiffness had gone, her body now limp. She was dead. There would be no autopsy, no investigation.

Perhaps Kushpreet’s father, Rai Singh Toor, was concerned that a neighbor would frame his family for a crime they didn’t commit, or bribe corrupt local police to do so. Or perhaps he was thinking of how to turn the tragedy around to get his family into Canada. He would say later that he did not suspect Dhillon of anything. Sukie was next in line. Dhillon always spoke highly of Sukie. He obviously was attracted to her, too.

The next day, Kushpreet’s aunt told Dhillon the news in person. Dhillon’s expression did not change. His face remained passive, bland even, as he digested the words. Had he heard what she said? He left her for a moment, made a phone call. He finally spoke.

“Why is this happening to me?” he said flatly. “Parvesh died, and now Kushpreet. All so quickly.”

In Tibba, Aunt Iqbal helped the other women prepare Kushpreet for cremation. The young body was marked with bluish spots, mostly on her back but some on the inner thighs and arms. What could she have eaten that would have done this, wondered her aunt. She bathed the body, rubbed it with yogurt. She dressed Kushpreet in a new red

lehnga

. Her face would be uncovered for the first stage of prayer, then covered with the

chunni

, or scarf. Mourners began to gather in Tibba. Visitors at the funeral asked Rai Singh how his daughter died.

lehnga

. Her face would be uncovered for the first stage of prayer, then covered with the

chunni

, or scarf. Mourners began to gather in Tibba. Visitors at the funeral asked Rai Singh how his daughter died.

“It was a heart attack,” he said.

Dhillon was at the funeral. Intense mourning of a death is discouraged among Sikhs, especially if the deceased is elderly. Birth and death are considered partners because they are both part of the cycle of human existence, life being merely one step toward nirvana, or complete unity with God. But Kushpreet did not live a full life, so her funeral was much darker. Her body was wrapped in sheets, a red shawl placed on top. White would have been used if she had been unmarried. Men of the family carried her body on a ceremonial wooden stretcher from the family’s home down the narrow sun-baked alley.

The procession emerged onto a dirt path, fields of corn and cane as far as the eye could see on each side, along to the site of the

small white

gurdwara

and a funeral pyre block. Ancient banyan trees stood like old gray men, branches sprouting tendrils that crept down the trunk and into the ground like veins grasping for life. At the pyre was the smooth concrete floor with streaks of scorched black, surrounded by six pillars supporting a brick roof. The roof was pierced by steel grates to allow airflow to enhance burning.

small white

gurdwara

and a funeral pyre block. Ancient banyan trees stood like old gray men, branches sprouting tendrils that crept down the trunk and into the ground like veins grasping for life. At the pyre was the smooth concrete floor with streaks of scorched black, surrounded by six pillars supporting a brick roof. The roof was pierced by steel grates to allow airflow to enhance burning.

The funeral pyre where Kushpreet was cremated.

The men of the family lifted the body onto the stack of dried logs on the floor, then covered her with more logs. Tradition says the husband lights the pyre. But Sukhwinder Dhillon was not there in time for the lighting. It was left to Kushpreet’s father, Rai Singh, to walk around the pyre and touch a flaming stick to hay stacked at the base of the wood. Soon it burst into orange flames spewing black smoke. It burned all afternoon.

When he arrived, Dhillon hugged Kushpreet’s parents in sympathy, his face now a forlorn mask.

“If I’d been with Kushpreet when she died,” he said, “you’d be blaming me right now.”

It was the spoiled child talking once more, taunting grieving parents, purporting to offer an alibi while at the same time blatantly, foolishly implicating himself.

As the logs crackled, a man approached Rai Singh. He said he was visiting from Canada, near Hamilton, Ontario. Dhillon’s city. “My condolences,” he said. Rai Singh nodded. The man continued. “Have you heard about this Dhillon guy? He was married twice before.” Rai Singh did not believe him. And blaming

Dhillon would do nothing to get his family to Canada. Later that day, Dhillon mentioned Kushpreet’s sister Sukie. What about her? Rai Singh said he’d support the marriage. Dhillon instantly agreed. It should be done as quickly as possible, because he had to return to Canada soon. Dhillon climbed back into his Maruti, drove down the cobblestone laneway, a smile on his face.

Dhillon would do nothing to get his family to Canada. Later that day, Dhillon mentioned Kushpreet’s sister Sukie. What about her? Rai Singh said he’d support the marriage. Dhillon instantly agreed. It should be done as quickly as possible, because he had to return to Canada soon. Dhillon climbed back into his Maruti, drove down the cobblestone laneway, a smile on his face.

CHAPTER 7

BIGAMY AND MURDER

Dhillon did not attend the

bhog

for Kushpreet. His absence from the family’s traditional nine-day mourning period angered her grieving relatives. Nevertheless, Rai Singh pushed ahead to expedite the marriage to Sukie. He drove to Ludhiana and obtained a death certificate for Kushpreet from a city hospital. She had never been to that hospital, but this was the way bureaucracy worked in India. Any document was available for the right price, no questions asked. The bogus certificate said she died of natural causes. Rai Singh then drove to Dhillon’s home to give him a copy for Sukie’s immigration application and to ask for more time to raise money for the dowry and wedding.

bhog

for Kushpreet. His absence from the family’s traditional nine-day mourning period angered her grieving relatives. Nevertheless, Rai Singh pushed ahead to expedite the marriage to Sukie. He drove to Ludhiana and obtained a death certificate for Kushpreet from a city hospital. She had never been to that hospital, but this was the way bureaucracy worked in India. Any document was available for the right price, no questions asked. The bogus certificate said she died of natural causes. Rai Singh then drove to Dhillon’s home to give him a copy for Sukie’s immigration application and to ask for more time to raise money for the dowry and wedding.

Dhillon had other business. He returned to Sukhwinder Kaur’s home in Dhandra where he spoke softly, warmly to her parents. Then Dhillon told them he had changed his mind about marrying Sukhwinder Kaur in Canada. It would take too much time, he said. They should do it here, in India, before he left. The family agreed. Ten days later Dhillon married for the fourth time. His new bride wed him at a

gurdwara

in Ludhiana, with a reception at Gurpal Palace.

gurdwara

in Ludhiana, with a reception at Gurpal Palace.

Meanwhile, by the end of February, in the village of Panj Grain, Sarabjit’s father grew restless with Dhillon. The tension had been building even before the babies had died. Why hadn’t Dhillon taken his daughter to Canada yet? Whenever he reached Dhillon by phone in Ludhiana—a chore in itself—there was a story. Dhillon was getting papers ready. He was talking with government people. He had business deals on the go. He always had an excuse. Dhillon finally dropped in to see Sarabjit. People are spreading lies about him, he said. And he said he had heard stories about

her

—that in fact she was actually 30 years old and had been married before, already had children. Sarabjit was furious.

her

—that in fact she was actually 30 years old and had been married before, already had children. Sarabjit was furious.

“You bring me the people who said that, and if I’m married, why don’t you take me to the person I’m married to!”

In March, Sarabjit, her uncle Iqbal, and Dhillon visited her grandparents in a village called Mairu. They ate dinner together. In front of the grandparents, Dhillon again mentioned the “rumors”

about Sarabjit. Her grandfather grew upset. “Why are you saying these things?” he demanded.

about Sarabjit. Her grandfather grew upset. “Why are you saying these things?” he demanded.

Dhillon told Sarabjit that he had to return to Ludhiana, alone, to prepare for his return trip to Canada. He would continue to make arrangements to bring her over at a later date. She didn’t believe a word. He left. It was the last time Sarabjit ever saw Dhillon in India.

Once he was back in Canada, the rumors about Dhillon ran hotter than ever in Punjab. Some wrote letters that landed on the desk of Pierre Carrier at the Canadian High Commission in New Delhi. Carrier was an RCMP liaison officer. He saw accusatory, “poison-pen” letters like this all the time. There were so many of them that, without any additional query by official Indian or Canadian authorities, they went unexamined. A Sikh man who made it to Canada who is a bigamist and a murderer who should be deported? Right. In the air-conditioned cool of the High Commission office, the latest letters were filed with the rest of the stack. Case closed? There was no case.

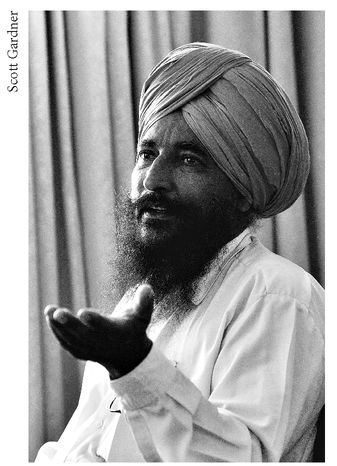

Iqbal Singh, Sarabjit’s uncle

Other books

Xenoform by Mr Mike Berry

The Choir Director 2 by Carl Weber

Insecure by Ainslie Paton

B0041VYHGW EBOK by Bordwell, David, Thompson, Kristin

My Wicked Enemy by Carolyn Jewel

Separate Cabins by Janet Dailey

Earth and High Heaven by Gwethalyn Graham

Melissa Explains It All: Tales From My Abnormally Normal Life by Melissa Joan Hart