Pompeii (49 page)

Authors: Mary Beard

The favourite candidates for the Pompeian stage have usually been various Italian genres. Often cited have been so-called ‘Atellan farces’, a type of comedy of which only a few fragments survive, but is supposed to have been originally an Oscan invention. Featuring stock characters such as Manducus, the glutton, or Bucco, the braggart, they have been compared to the Morality Plays of the Middle Ages. Also in the frame are other styles of Roman comedy, such as survive in the plays of Plautus and Terence, and even performances that are not theatrical in our sense of the word. One idea is that the Covered Theatre was not designed for drama at all, but was built to be the assembly hall of the early colonists.

All of these suggestions are perfectly possible, but no more than that. Some careful detective work, however, does allow us to get a little closer to the staples of the Pompeian stage. Scholars have only recently turned their attention to two genres of theatrical performance, again very largely lost, that were hugely popular, among emperors as well as paupers, in Italy during Pompeii’s last hundred years or so. They are mime and pantomime. Mime came in many forms, performed as street entertainment, in private houses, as short interval entertainment in the theatre and as the main feature. Ribald comedy, going under such titles as ‘The Wedding’, ‘The Fuller’ or ‘The Weaving Girls’ (perhaps, as one scholar has suggested, the ancient equivalent of a play called ‘The Swedish Masseuses’), it was played by both male and female actors who, unusually, did not wear masks. Sometimes it was improvised according to the lines of a plot invented by the

Archimimus

(‘chief mime’); sometimes it was scripted. Despite the title and our own understanding of ‘mime’, it was not silent – but a mixture of words, music and dance.

Pantomime was a different genre, usually tragic rather than comic, and certainly not to be confused with the modern performances of the same name. Ancient pantomime is more the ancestor of modern ballet than of our ‘pantomime’. Said to have been introduced to Rome in the first century BCE, it featured a star performer who gave a virtuoso display of dance and mime (in our sense of the word ‘mime’) to a libretto that was sung by the supporting members of the troupe, male and female. These formed a vocal ‘backing group’, along with others who provided the music. The

scabellum

, or large castanets, was a distinctive, and noisy, part of the show. The star alone took all the different roles in the plot, hence the title: ‘

panto

– mime’, or ‘miming

everything

’. In the process, he changed his mask (which had a closed rather than an open mouth, as in conventional ancient theatre) to indicate the different parts he was adopting. All kinds of themes were performed, drawn from the repertoire of classic Greek tragedy, Euripides’

Bacchae

, for example, or the story of Iphigeneia. Historians now reckon that there was more to pantomime than just degenerate theatre. It was probably one of the main ways that the general population in the Roman world picked up their knowledge of Greek myth and literature.

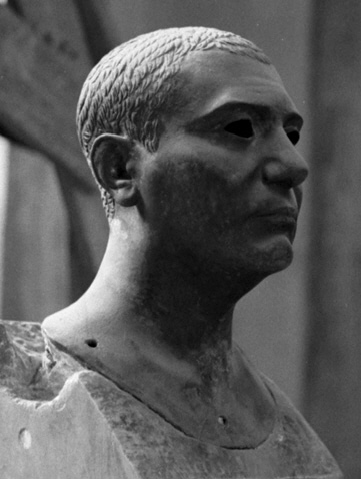

There are clear signs that mime and, especially, pantomime were major attractions at Pompeii, in the theatre and at other venues. A portrait set up in the Temple of Isis commemorates a man called Caius Norbanus Sorex ‘a player of second parts’. Another statue of the same man stood in the Building of Eumachia in the Forum (the inscribed base, though not the portrait itself, survives), and another in the sanctuary of Diana at Nemi, just outside Rome, where he is called ‘mime actor in second parts’. He was presumably a member of a travelling mime company who worked in various places in central and southern Italy. Though not the lead player in his troupe, he had done enough in Pompeii (maybe he contributed to the restoration of the Temple of Isis after the earthquake) to be honoured by two bronze portraits. The fact that, as an actor, he was legally

infamis

(‘disgraceful’) did not seem to get in the way of public commemoration, ‘on land given by decision of the town council’, in the centre of Pompeii.

88. Actor and benefactor? Although he was a member of a ‘disgraceful’ profession, this is one of two bronze portraits in Pompeii to have publicly honoured the mime actor Caius Norbanus Sorex. Another portrait of the same man is known from Nemi, near Rome.

We have already seen a few hints of pantomime performance in the city. According to the exact words of his tombstone, the shows presented by Aulus Clodius Flaccus at the games of Apollo (p. 198) featured ‘pantomimes, including Pylades’. Pylades was the name of the emperor Augustus’ favourite pantomime performer, who played at some of his private dinner parties. It may be that this notable performer himself was brought to Pompeii by the generosity of Flaccus, or it may be a later star who had adopted a famous theatrical name – a common, but for us confusing, practice among ancient actors. Another tomb inscription, the epitaph of Decimus Lucretius Valens (p. 211), gives us a passing reference to the loud music of the pantomime. For, if my translation is correct, the ‘clapper beaters’ or ‘castanet players’ (

scabiliari

) were one of the groups who had honoured the dead man with statues.

89. This wallpainting from a private house in Pompeii may well evoke pantomime performances. Various characters are shown against a façade similar to that of the Large Theatre.

The enthusiasm of the Pompeians for pantomime can be detected in a handful of difficult to decipher, poorly preserved, but intriguing graffiti. They seem to refer to different members of a pantomime troupe headed by one Actius Anicetus, who is also found at nearby Puteoli under the name of ‘Caius Ummidius Actius Anicetus, the pantomime’. ‘Actius, star of the stage’ reads one apparent fan message scrawled on a tomb outside the city wall, ‘Here’s to Actius, come back to your people soon,’ reads another. And it may be that those who occasionally call themselves ‘Anicetiani’ are the self-styled fans of Anicetus, rather than other members of his troupe. Some of those supporting members can, in any case, be tracked down in other graffiti at Pompeii. In the private bath of a large house someone has written the words

histrionica Actica

or ‘Actius’ showgirl’, perhaps an admirer of a female member of the company, who did not know her exact name. Elsewhere a man called Castrensis appears often enough in graffiti alongside Actius Anicetus for us to imagine that he too is another player in the troupe. So also does a ‘Horus’: ‘Here’s to Actius Anicetus, here’s to Horus’ as one graffito runs. We seem to be dealing with a popular group of perhaps seven or eight players altogether.

With the popularity of pantomime in mind, we can return to the paintings on the walls of Pompeii. For tucked away among all those evocations of the distant world of classical Greek theatre there are one or two that may in fact capture the more staple fare of the Pompeian stage. One likely candidate is an overblown painting of a stage set which is now faded almost beyond recognition. But in earlier drawings we see what looks very much like the elaborate architectural backdrop of the stage that is found in the Large Theatre of Pompeii, with its large central doorway (Ill. 89). A clever suggestion is that this particular design reflects a pantomime on the theme of the myth of Marsyas, who picked up the flutes of the goddess Minerva and challenged Apollo to a musical contest. If so, we see in the main openings of the stage, from left to right, Minerva, Apollo and Marsyas, as they would be portrayed in turn by the star dancer. The chorus, meanwhile, peep around the background.

This may be the closest we can now get to the Pompeian theatre.

Bloody games

A day out for the Pompeians could involve a much bloodier spectacle than this harmless if raucous pantomime. When Lord Byron coined the famous phrase ‘butchered to make a Roman holiday’, he meant exactly that. One of the ways that Romans spent their leisure time was watching men pitted against wild animals, and the combat of gladiators, who sometimes fought to the death. An enormous amount of scholarly effort has been spent in trying to discover where and when gladiators in particular originated. Did they come to Rome via the mysterious Etruscans? Was the institution a south Italian era invention from the region of Pompeii itself? Did it have its prehistoric origins in human sacrifice? And perhaps even more effort has been devoted to working out why the Romans were so keen on such practices anyway. Were they a substitute for ‘real’ warfare? Did they function as a collective release of tension in a highly ranked and rule-bound society? Or were the Romans even more bloodthirsty than those modern audiences who are happy to watch boxing or bull-fighting?

The material that survives from Pompeii does not help much with those questions. Their answers will always remain speculative at best. What we do get from the buildings, paintings and graffiti in the town is the best insight from anywhere in the Roman world into the practical infrastructure and organisation of wild-beast hunts and gladiatorial games, and into the lives (and deaths) of the gladiators themselves. We have posters advertising the shows and the facilities offered. We can visit the gladiators’ barracks and see what they wrote on their own walls. We can even inspect cartoons of real gladiatorial fights, recording the results of the contest, and whether the losing fighter was killed or let off with his life. We come closer here to the day-to-day culture of the Roman Amphitheatre than we do by reading the bombastic accounts in ancient writers of the blockbuster shows occasionally presented by Roman emperors, with – or so the writers claim – their mass human carnage and whole menageries of animals put to death.

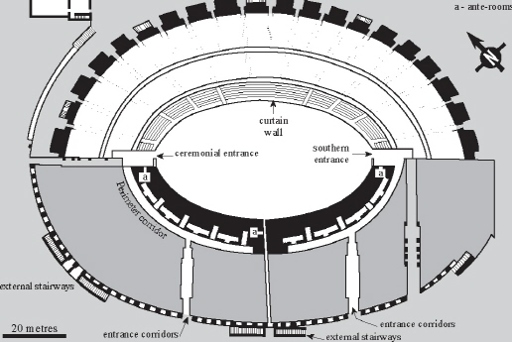

Figure 20

. The Pompeian Amphitheatre. The plan shows the pattern of the seating (above), and (below) the system of internal corridors and access ways which ran underneath the seating, largely invisible from above.

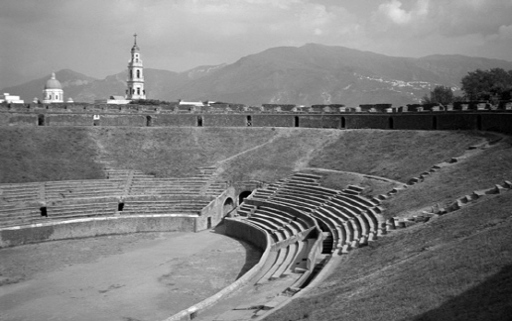

The Amphitheatre, where most of the gladiatorial shows and hunts took place, is still one of the most instantly impressive monuments in the whole city of Pompeii. Built at the very edge of the town, thanks to the generosity of Caius Quinctius Valgus and Marcus Porcius in the 70s BCE (pp. 40, 42), it is the earliest permanent stone building of its type to be found anywhere and is of a substantial size even by metropolitan Roman standards. The Colosseum in Rome, which was built 150 years later in a city with a total population of around a million, is only just over twice as big: the Colosseum could accommodate about 50,000 spectators, the Pompeian Amphitheatre some 20,000. Amphitheatres now can be disappointing to visit: high on initial impact, but low on rewarding details. They do not always repay careful inspection. In Pompeii, however, we can piece together from what has been discovered the Amphitheatre’s sometimes surprising history.