Pompeii (23 page)

Authors: Mary Beard

The painters were working, as the eruption began, on the large middle zone of decoration. They were using true fresco technique. That is to say, the paint was being applied to the plaster while it was still wet, which – as the paint bonds with the plaster – produces a much more stable colour, which does not flake off at a single knock. But it also means that they had to work very quickly, to be certain that the paint was on before the plaster had dried. Painters in the Renaissance had the exactly same problem and sometimes hung damp cloths over the plaster to keep it moist. Keen eyes have occasionally spotted what might be such cloth marks in other houses in Pompeii, but not here. So too, on other paintings, it is possible to detect the pressure marks, where the painter has pressed down on the plaster to try to bring the remaining moisture to the surface.

43. A half-finished wall, abandoned by the painters when the eruption came. At first sight this is not much to look at, but it is possible to reconstruct some of the painters’ methods. The central and right-hand panel had already been given their wash of colour – except for the central figured scene for which the design had been merely sketched out. The left hand section (just visible) was still covered in bare plaster. At the bottom of the central panel painted cupids are enjoying a perilous chariot race.

A closer look at the north wall gives a good idea of exactly the stage they had reached (Ill. 43). Two of the main panels, one black and one red, had already been completed. They were mostly plain, but enlivened by several groups of tiny figures: including what looks like an amorous god making off with a nymph, and some sporting cupids, racing their chariots pulled by goats (with a nasty accident to the leading pair). Separating these panels of colour were narrower sections, where fantastic architecture and impossibly attenuated columns were intertwined with flowers, foliage and precariously balanced birds. On the left, a whole section remained to be painted: the final layer of fine plaster was still wet and would presumably have been coloured in matching black by the end of the day – had disaster not struck.

Also in the final stages was the main picture that was to have been the focal point in the very centre of the wall. Here a rough drawing, in yellow ochre, had been made in the wet plaster to plan out the design and guide the painter in what would have to be speedy work on the final image. All that we can tell now is that it would have included a number of figures (someone seated on the left, and a several standing on the right) and that the upper portion, where some paint had already been applied, was to be blue: presumably, as many other surviving examples make almost certain, it would have been a scene drawn from the repertoire of mythology. In this panel, the under-drawing was relatively detailed, with some careful modelling of the anatomy.

The same was not true for those delicate architectural images. On the east wall of the room, these are still unfinished – but here the sketch in the plaster amounts to no more than some schematic straight lines, geometric curves (hence the compasses) and the occasional diagram of a tricky shape, such as urns. It is as if these elegant and apparently whimsical designs were so much the stock-in-trade of the painters that they could fill in the detail – the birds and the foliage, the architectural extravaganzas – from only the most skeletal outline.

We cannot be more certain about the planned subject of that central panel of the north wall for the simple reason that most of its under-drawing has been covered by a rough layer of irregular dripping plaster. But this turns out to give us another glimpse into how the painters were working. For this pattern of plaster can only have been caused by a bucketful of the stuff falling against the wall from a ladder or scaffolding, knocked over when the painters made their escape or when the eruption came. Underneath the central panel, the two holes at either side, with a line running between them, suggest that a temporary shelf had been rigged up here, to hold the paint pots of the man painting the main scene.

Chemical analysis of the surviving paints yields further hints. They were using seven basic colours (black, white, blue, yellow, red, green and orange), made up in different shades from fifteen different pigments. Some must have been easy to get hold of locally: soot, for example, gave them their black, and various forms of chalk or limestone produced white paints. But they were also using more distant or sophisticated ingredients: celadonite, perhaps from Cyprus, for green; haematite for red, also probably imported; and so-called ‘Egyptian blue’ made commercially by heating together sand, copper and some form of calcium carbonate (according to Pliny, this was at least four times as expensive as a basic yellow ochre). These paints came in two significantly different types. The first included an organic ‘binder’ (probably egg). The second had no such binder but had been mixed with water. This points to two different painting techniques. The binder was needed in the paint used for the finishing touches (extra twirls on the architectural designs, or even those racing cupids) which were applied secco, that is onto plaster or paintwork that was already dry. It was not used in the paint applied directly onto the wet plaster (fresco).

Putting all this evidence together, we can get a rough outline of the team which was doing this work, and of its division of labour. It must have involved at least three workers. On the morning of 24 August, one was busy on the central panel of the north wall. One was working next to him, charged with the less skilled task of putting on the plain wash of black paint (perhaps it was his bucket of plaster that fell). Another was painting the as yet unfinished architectural decoration on the east wall (the central panel there had not yet been plastered, so was due to be painted on a later day). Another may have been at work on the secco details. But as there was no time pressure with these (unlike the fresco), they would more likely have been added by the other painters when their fresco work was finished. A small business then: with an apprentice, son or slave supporting the work of a couple of more experienced craftsmen.

Who exactly they were, how they were hired, what they charged or how the wall designs they were creating were chosen, we can only guess. Only two possible signatures have ever been found on paintings at Pompeii, and we have no local evidence of prices for such work. The best we have, in fact, comes from much later, in a set of imperial regulations about maximum prices issued in the early fourth century. In this a ‘figure painter’ (who may be the equivalent of those here who painted the central panels) could earn twice as much per day as a ‘wall painter’, and three times as much as a baker or a blacksmith. If the ‘figure painter’ is the equivalent of those who worked here on the central panels (rather than, as some scholars believe, a portrait artist), then such decoration must have been pricey, but hardly a luxury affordable only by the very rich. The negotiations between client and painter were probably not all that different from those we know today. A lot of money will buy you anything you choose. Otherwise it is a trade-off between the wishes and whims of the clients and the preferences of the painter, his competence and his established repertoire.

44. The painting that gave its name to the House of the Menander. The fourth-century BCE comic playwright Menander is here seen relaxing with a scroll of his own work.

What is certain is that the distinctive painting of Pompeian houses, their vivid decorative schemes, the colourful assault they make on the visual senses were almost all the product of the kind of working methods and small-scale business we glimpse in the House of the Painters at Work. A small property, down a back street just two doors away from Amarantus’ bar, was most likely the home base of one such painting business, or at least of a family which made part of its living in that way. Near the front door, a wooden cupboard originally stood, containing more than a hundred pots of paint, as well as other tools, such as plumb-bob and compasses, spoons and spatulas, and grinding equipment for turning the pigments into fine powder ready for mixing. Taking account of itinerant labour or even special commissions from prestige firms outside the area, a small number of workshops like this must have been responsible for the majority of the painted houses in Pompeii, and so there must be plenty of examples of the same painter’s work in different properties.

Spotting the work of the same ‘hand’, where there is no written evidence to help, is a seductive but dangerous business. One very distinguished archaeologist has even managed to convince himself that he can spot the very same painter at work at Fishbourne in England, in the so-called ‘Royal Palace’ of Togidubnus, and at Stabiae, just south of Pompeii. In Pompeii itself, all kinds of – sometimes wild – theories of ‘who painted what’ have been floated. So, for example, the work of the painter responsible for several of the main figured scenes in the House of the Tragic Poet has also been identified in more than twenty other houses in the town, from the famous painting of Menander in the House of the Menander (Ill. 44) to a matter-of-fact picture of a man relieving himself that decorates a corridor on the way to the latrine in a small house plus shop. Maybe – or maybe not. But, to indulge in the same game myself for a moment, the tiny vignette of the cupids in the chariot accident on the painted border of that north wall we have been looking at is so similar to a scene with cupids in the House of the Vettii (Plate 21) that it is hard to imagine that they are not by the same painter or painters.

Pompeian colours

If the painters had not been interrupted, the finished product in the House of the Painters at Work would have been something very close to the ‘Pompeian painting’ of modern imagination. For the rediscovery of Pompeii in the eighteenth century launched a widespread European fashion for ‘Roman’ interior design. Travellers who had paid a visit to the ruins, or those who had merely enjoyed some of the lavish early publications of the decorations found there, began to reinvent the walls of Pompeii in their own houses, whether in city-centre Paris or the English countryside. Anyone with the money could re-create the ambience of a Roman room by following a simple formula: walls painted in panels of that deep red colour now known as ‘Pompeian red’ (or in an almost equally characteristic yellow), decorated with fantasy architecture, floating nymphs and scenes drawn from classical myth. For us, this has become the stereotype of Pompeian domestic style.

It was not, of course, simply an invention. Indeed, this ‘Pompeian style’ reflects the commonest format of domestic decoration in the ancient town. That deep red was one of the Roman colours of choice, along with black, white and yellow (though we should not forget that the heat of the volcanic debris may have produced more red than there once was, by discolouring what was originally painted yellow). Many designs combine mythological scenes, ranging from such sultry subjects as Narcissus admiring his own reflection in the pool to the menace of Medea about to draw her sword on her children, with exuberant versions of architectural form. These are sometimes precariously spindly, sometimes so successful a

trompe l’oeil

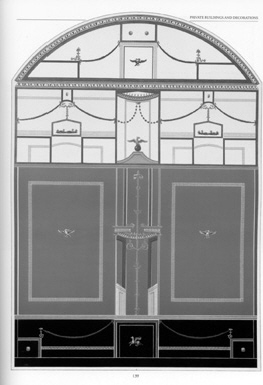

, revealing vistas extending far into the distance, that the solid surface of the wall itself seems almost to disappear. Another distinctive feature, as we saw in the unfinished room and as is carefully replicated in modern imitations, is the three-fold division of the design into three vertical registers: a broad central section carrying the main figured scenes, with dado below and an upper zone carrying more decoration above the cornice (Ill. 45).