Pompeii (27 page)

Authors: Mary Beard

55. King Agamemnon, on the left, cannot bear to look as his daughter Iphigeneia is taken off to be sacrificed to the goddess Artemis, who is appearing in the heavens. This drawing (like Ill. 53) is from the famous nineteenth-century guide book to the site,

Pompeiana

by Sir William Gell.

In all likelihood the Pompeian painters were working from a range of well-known and ‘quotable’ masterpieces which had entered their own artistic repertoire. There is no reason at all to suppose that they had ever seen the original paintings or even that they had pattern books or exact templates to copy. These famous images were as much part of the common artistic currency as the

Mona Lisa

or Van Gogh’s

Sunflowers

are in the West today. As such they could be adapted to new locations at will, riffed and improvised, made to

evoke

the original rather than to

reproduce

it exactly. And not only in paint. Achilles on Skyros turns up in mosaic too, and one popular theory has it that the Alexander mosaic in the House of the Faun is a version of a painting by a Greek artist, Philoxenus of Eretria, mentioned by Pliny.

The big question, though, is what the Pompeian residents made of all these myths decorating their walls. Was it the ancient equivalent of wallpaper, occasionally glanced at and admired maybe, but always in the background? Would, in fact, many of the Pompeians have found it as difficult as we do to explain exactly what was going on in many of these images? Or were they carefully studied, loaded with meaning, and intended to convey a particular message to the viewer? And if so, then what message?

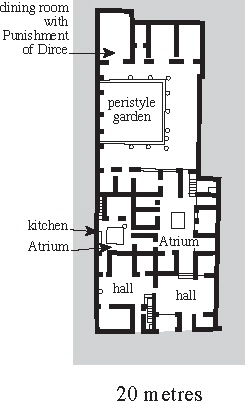

Figure 12

. The House of Julius Polybius. This has an unusual arrangement of large entrance halls, as well as the standard atrium. It was in this house that the twelve victims of the eruption were discovered, in rooms off the peristyle.

Archaeologists divide on the question. Some see little more than attractive decoration in most of these images. Others like to detect complex, even mystical significance in the painted plaster. Of course, the paintings no doubt spoke differently to different people, and some observers were more observant than others. But there are a number of hints that viewers on occasion took notice of the images that surrounded them, or at least were expected to. Even if the most ingenious modern theories – which would see the interior decoration of many Pompeian houses as an elaborate mythological ‘code’ – are decidedly unconvincing, some painters and patrons astutely planned their content and arrangement.

Ancient writers tell vivid stories of the impact a mythological painting could make on a viewer. A Roman lady, about to part from her own husband, was once reduced to tears, it was said, at the sight of Hector, the Trojan hero, saying his final farewell to his wife Andromache (he was going off to battle, one from which he would never return). There are no tears at Pompeii. But one person who had a very good idea of what he was looking at, and took the time to reflect on it, has left a record of his reflections – and it probably was

his

– scrawled on a wall in the House of Julius Polybius (Fig. 12). In the grandest room off its peristyle garden is a large painting of another favourite scene in the repertoire of Pompeian myths: the punishment of Dirce – a gory tale, in which (to cut a very long story short) her victims take revenge on Dirce, the Queen of Thebes, by tying her to the horns of a wild bull, and so inflicting a slow, painful and bloody death. In Pompeian terms, there is nothing particularly remarkable about the painting, one of eight on the same theme discovered in houses of the city. But this particular version made enough of an impression on our writer that he advertised it, in a one-line graffito, found in one of the service areas of the property: ‘Look. There’s not only those Theban women, but Dionysus and the royal maenad too.’

Unearthed before the painting had been found, this message at first puzzled the archaeologists who were excavating the house in the 1970s. What was some scribbler doing in the kitchen, rambling on about Theban women? It only fell into place when it was put together with the nearby image. For, as well as the final punishment of Dirce with the bull, the painting also depicts the scene of her capture dressed as a follower of Dionysus (the ‘royal maenad’ of the graffito), as well as a shrine of the god and, in the foreground, a larger group of maenads (‘those Theban women’). Whoever wrote the graffito had not only paid careful attention to the painting, but knew enough of the story to identify the scene as Thebes, and Dirce (as written versions of the myth insist) as a follower of Dionysus. Exactly what prompted him to write, who knows? But whatever it was, he would no doubt have been amazed to discover that his words have become, 2000 years on, rare and clinching proof that some people in the city certainly cast an intelligent eye on the pictures on their walls.

On other occasions a particular subject in a particular location clearly implies some calculated choices on the part of painter or patron. Whoever decided to decorate the wall above one of the couches of the outdoor dining installation in the House of Octavius Quartio with a painting of the mythical Narcissus gazing at his own reflection in the pool must have thought that the diners would enjoy the joke. For this was one of those upmarket installations (as in the House of the Golden Bracelet), with a gleaming channel of water between the pair of couches on which the company reclined. Presumably as you gazed at your reflection in the water, you were supposed to enjoy a wry smile at the overlap between myth and real life, while reflecting, perhaps, on the myth’s lesson about the tragic consequences of falling in love with that image of yourself.

There may be a similar pointed reference lying behind the painting of Micon and Pero in the House of Lucretius Fronto, with its verses underlining the combined virtues of modesty or a sense of decency (

pudor

) and piety (

pietas

) which the story celebrates. Though some archaeologists have thought this an apt decoration for a child’s bedroom (a strange choice, if you ask me), there may be a more specific political resonance to the image. Is it just a coincidence that, in a couple of lines of poetry painted on the outside of this house as an electoral jingle, it is the

pudor

of Marcus Lucretius Fronto which is given pride of place?

If decency [

pudor

] is thought to help a man get on in life at all

To our Lucretius Fronto that high office which he seeks should fall

If Marcus Lucretius Fronto really was the occupant of this house (and the combination of graffiti inside and outside makes that very likely), then it looks as if the painting was meant to reflect one of his trademark public virtues.

But, even more often, the

combination

of subjects chosen to decorate a room seems to be significant. The removal of figured panels from their original setting to the safety of the museum certainly did much to preserve their colour and detail. Yet it also makes it hard to see them in their original context and the relationship between them in their original position. In the House of the Tragic Poet, for example, many of the paintings, now displayed in the Naples Museum as if they were individual examples of gallery art, once combined to make a connected cycle of themes from the Trojan War: Helen leaving for Troy with Paris; the sacrifice of Iphigeneia; his prized captive and concubine Briseis being removed from Achilles – the cause of his quarrel with Agamemnon which launches Homer’s

Iliad

and which was depicted in another panel in the house. There was more to this than a simple coherence of theme. In their original locations, all kinds of questions must have been raised in the clever visual juxtapositions and in the ‘provocative correspondences’ between individual paintings and their subjects.

Originally, it seems, the scenes of Helen and Briseis stood in adjacent panels in the atrium (Plate 23). These were two vignettes of women’s desertion, each one a linch-pin in the story of the Trojan War, and the parallels are underlined by the similar dress of each woman, her bowed head and the surrounding cast of soldiers. Yet, for anyone familiar with the Trojan story, the comparison must have prompted reflection on the differences between the two scenes as much as on the similarities. For Helen, the Greek queen, was leaving her husband Menelaus and embarking on an adulterous journey of her own free will – and in so doing would be the catalyst to the whole catastrophic war between Greeks and Trojans. Briseis, the Trojan prisoner of war, was leaving Achilles to be handed over to King Agamemnon, against her will – and Achilles’ anger at his loss would lead directly, as Homer’s epic tells, to the death of his friend Patroclus and of Hector, prince of Troy. Virtue, blame, status, sex, motivation and the causes of suffering are all at issue in this pairing. Whoever designed this series of images certainly knew their Trojan myths and must have expected the audience to do so likewise.

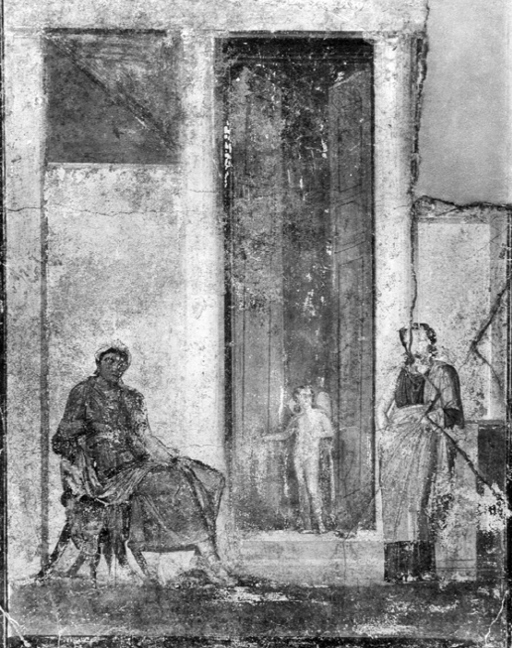

56. A little cupid stands at the doorway as Paris and Helen decide to elope, so launching the Trojan War. But this painting from the House of Jason is more loaded than it might seem at first sight. For here Paris is sitting down as if taking the female role, while Helen stands – and the architectural background is reminiscent of Pompeii itself, suggesting that the myth of adultery, elopement and domestic disruption was relevant to ‘real life’ too.

An unsettling undertone can be detected in another series of paintings, which also features Helen’s adultery with Paris. Three panels decorate a small room in the House of Jason, so called after a painting of the Greek hero Jason in another room. Each one depicts a moment of calm before tragedy strikes: Medea watches her children play, before killing them, to take revenge on the husband who has abandoned her; Phaedra talks to her nurse before killing herself in unrequited love for her stepson Hippolytus, accusing the innocent young man of incest in the process; while Helen entertains Paris at her marital home before their elopement – which is already signalled by the little cupid at the door (Ill. 56).

As with the series in the House of the Tragic Poet, visual rhymes between the paintings prompt the viewer to compare and contrast the different versions of domestic disaster on show. For example, both Medea and Phaedra are seated, as you would expect of a respectable Roman matron; but in the other scene it is Helen who stands, while her effeminate ‘Oriental’ lover takes the women’s place. But the architectural background adds a disturbing dimension. Its similiarity in each scene does not just bind the three stories together; the style of the architecture and those big heavy doors bear more than a passing resemblance to the style of upmarket domestic architecture in Pompeii itself. It is almost as if the paintings have a point to make about the relevance of the myth to contemporary Roman life, in exposing the tragic dysfunction – from adultery to infanticide – that can creep up on any family, anywhere.

A room with a view?