Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945 (13 page)

It is thus hard to know how far the trials of Nazis contributed to the political and moral re-education of Germany and the Germans. They were certainly resented by many as ‘victors’ justice’, and that is just what they were. But they were also real trials of real criminals for demonstrably criminal behaviour and they set a vital precedent for international jurisprudence in decades to come. The trials and investigations of the years 1945-48 (when the UN War Crimes Commission was disbanded) put an extraordinary amount of documentation and testimony on record (notably concerning the German project to exterminate Europe’s Jews), at the very moment when Germans and others were most disposed to forget as fast as they could. They made clear that crimes committed by individuals for ideological or state purposes were nonetheless the responsibility of individuals and punishable under law. Following orders was not a defense.

There were, however, two unavoidable shortcomings to the Allied punishment of German war criminals. The presence of Soviet prosecutors and Soviet judges was interpreted by many commentators from Germany and Eastern Europe as evidence of hypocrisy. The behaviour of the Red Army, and Soviet practice in the lands it had ‘liberated’, were no secret—indeed, they were perhaps better known and publicized then than in later years. And the purges and massacres of the 1930s were still fresh in many people’s memory. To have the Soviets sitting in judgment on the Nazis—sometimes for crimes they had themselves committed—devalued the Nuremberg and other trials and made them seem exclusively an exercise in anti-German vengeance. In the words of George Kennan: ‘The only implication this procedure could convey was, after all, that such crimes were justifiable and forgivable when committed by the leaders of one government, under one set of circumstances, but unjustifiable and unforgivable, and to be punished by death, when committed by another government under another set of circumstances.’

The Soviet presence at Nuremberg was the price paid for the wartime alliance and for the Red Army’s pre-eminent role in Hitler’s defeat. But the second shortcoming of the trials was inherent in the very nature of judicial process. Precisely because the personal guilt of the Nazi leadership, beginning with Hitler himself, was so fully and carefully established, many Germans felt licensed to believe that the rest of the nation was innocent, that Germans in the collective were as much passive victims of Nazism as anyone else. The crimes of the Nazis might have been ‘committed in the name of Germany’ (to quote the former German Chancellor Helmut

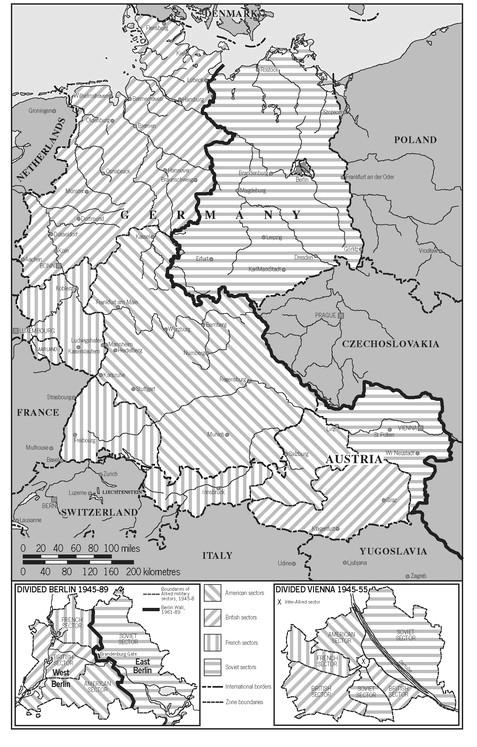

Germany and Austria: Allied Occupation Sectors

Kohl, speaking half a century later), but there was little genuine appreciation that they had been perpetrated

by

Germans.

The Americans in particular were well aware of this and immediately initiated a programme of re-education and denazification in their zone, whose objective was to abolish the Nazi Party, tear up its roots and plant the seeds of democracy and liberty in German public life. The US Army in Germany was accompanied by a host of psychologists and other specialists, whose assigned task was to discover just why the Germans had strayed so far. The British undertook similar projects, though with greater skepticism and fewer resources. The French showed very little interest in the matter. The Soviets, on the other hand, were initially in full agreement and aggressive denazification measures were one of the few issues on which the Allied Occupation authorities could agree, at least for a while.

The real problem with any consistent programme aimed at rooting out Nazism from German life was that it was simply not practicable in the circumstances of 1945. In the words of General Lucius Clay, the American Military Commander, ‘our major administrative problem was to find reasonably competent Germans who had not been affiliated or associated in some way with the Nazi regime . . . All too often, it seems that the only men with the qualifications . . . are the career civil servants . . . a great proportion of whom were more than nominal participants (by our definition) in the activities of the Nazi Party.’

Clay did not exaggerate. On May 8th 1945, when the war in Europe ended, there were 8 million Nazis in Germany. In Bonn, 102 out of 112 doctors were or had been Party members. In the shattered city of Cologne, of the 21 specialists in the city waterworks office—whose skills were vital for the reconstruction of water and sewage systems and in the prevention of disease—18 had been Nazis. Civil administration, public health, urban reconstruction and private enterprise in post-war Germany would inevitably be undertaken by men like this, albeit under Allied supervision. There could be no question of simply expunging them from German affairs.

Nevertheless, efforts were made. Sixteen million

Fragebogen

(questionnaires) were completed in the three western zones of occupied Germany, most of them in the area under American control. There, the US authorities listed 3.5 million Germans (about one quarter of the total population of the zone) as ‘chargeable cases’, though many of them were never brought before the local denazification tribunals, set up in March 1946 under German responsibility but with Allied oversight. German civilians were taken on obligatory visits to concentration camps and made to watch films documenting Nazi atrocities. Nazi teachers were removed, libraries restocked, newsprint and paper supplies taken under direct Allied control and re-assigned to new owners and editors with genuine anti-Nazi credentials.

There was considerable opposition even to these measures. On May 5th 1946, the future West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer spoke out against the denazification measures in a public speech in Wuppertal, demanding that the ‘Nazi fellow travellers’ be left in peace. Two months later, in a speech to his newly-formed Christian Democratic Union, he made the same point: Denazification was lasting much too long and doing no good. Adenauer’s concern was genuine. In his view, confronting Germans with the crimes of the Nazis—whether in trials, tribunals or re-education projects—was more likely to provoke a nationalist backlash than induce contrition. Just because Nazism

did

have such deep roots in his country, the future Chancellor thought it more prudent to allow and even encourage silence on the subject.

He was not altogether mistaken. Germans in the 1940s had little sense of the way the rest of the world saw them. They had no grasp of what they and their leaders had done and were more preoccupied with their own post-war difficulties—food shortages, housing shortages and the like—than the sufferings of their victims across occupied Europe. Indeed they were more likely to see themselves in the role of victim and thus regarded trials and other confrontations with Nazi crimes as the victorious Allies’ revenge on a defunct regime.

15

With certain honorable exceptions, Germany’s post-war political and religious authorities offered scant contradiction to this view, and the country’s natural leaders—in the liberal professions, the judiciary, the civil service—were the most compromised of all.

Thus the questionnaires were treated with derision. If anything they served mostly to whitewash otherwise suspect individuals, helping them get certificates of good character (the so-called ‘Persil’ certificates, from the laundry soap of the same name). Re-education had a decidedly limited impact. It was one thing to oblige Germans to attend documentary films, quite another to make them watch, much less think about what they were seeing. Many years later the writer Stephan Hermlin described the scene in a Frankfurt cinema, where Germans were required to watch documentary films on Dachau and Buchenwald before receiving their ration cards: ‘In the half-light of the projector, I could see that most people turned their faces away after the beginning of the film and stayed that way until the film was over. Today I think that that turned-away face was indeed the attitude of many millions . . . The unfortunate people to which I belonged was both sentimental and callous. It was not interested in being shaken by events, in any “know thyself.” ’

16

By the time the western Allies abandoned their denazification efforts with the coming of the Cold War, it was clear that these had had a decidedly limited impact. In Bavaria about half the secondary schoolteachers had been fired by 1946, only to be back in their jobs two years later. In 1949 the newly-established Federal Republic ended all investigations of the past behaviour of civil servants and army officers. In Bavaria in 1951, 94 percent of judges and prosecutors, 77 percent of finance ministry employees and 60 percent of civil servants in the regional Agriculture Ministry were ex-Nazis. By 1952 one in three of Foreign Ministry officials in Bonn was a former member of the Nazi Party. Of the newly-constituted West German Diplomatic Corps, 43 percent were former SS men and another 17 percent had served in the SD or Gestapo. Hans Globke, Chancellor Adenauer’s chief aide throughout the 1950s, was the man who had been responsible for the official commentary on Hitler’s 1935 Nuremberg Laws. The chief of police in the Rhineland-Palatinate, Wilhelm Hauser, was the

Obersturmführer

responsible for wartime massacres in Byelorussia.

The same pattern held true outside the civil service. Universities and the legal profession were the

least

affected by denazification, despite their notorious sympathy for Hitler’s regime. Businessmen also got off lightly. Friedrich Flick, convicted as a war criminal in 1947, was released three years later by the Bonn authorities and restored to his former eminence as the leading shareholder in Daimler-Benz. Senior figures in the incriminated industrial combines of I.G. Farben and Krupp were all released early and re-entered public life little the worse for wear. By 1952 Fordwerke, the German branch of Ford Motor Company, had reassembled

all

its senior management from the Nazi years. Even the Nazi judges and concentration camp doctors convicted under American jurisdiction saw their sentences reduced or commuted (by the American administrator, John J McCloy).

Opinion poll data from the immediate post-war years confirm the limited impact of Allied efforts. In October 1946, when the Nuremberg Trial ended, only 6 percent of Germans were willing to admit that they thought it had been ‘unfair’, but four years later one in three took this view. That they felt this way should come as no surprise, since throughout the years 1945-49 a consistent majority of Germans believed that ‘Nazism was a good idea, badly applied’. In November 1946, 37 per cent of Germans questioned in a survey of the American zone took the view that ‘the extermination of the Jews and Poles and other non-Aryans was necessary for the security of Germans’.

In the same poll of November 1946, one German in three agreed with the proposition that ‘Jews should not have the same rights as those belonging to the Aryan race’. This is not especially surprising, given that respondents had just emerged from twelve years under an authoritarian government committed to this view. What

does

surprise is a poll taken six years later in which a slightly higher percentage of West Germans—37 percent—affirmed that it was better for Germany to have no Jews on its territory. But then in that same year (1952) 25 percent of West Germans admitted to having a ‘good opinion’ of Hitler.

In the Soviet-occupied zone the Nazi legacy was treated a little differently. Although Soviet judges and lawyers took part in the Nuremberg trials, the main emphasis in denazification in the East was on the collective punishment of Nazis and the extirpation of Nazism from all areas of life. The local Communist leadership was under no illusions about what had taken place. As Walter Ulbricht, the future leader of the German Democratic Republic, put it in a speech to German Communist Party representatives in Berlin just six weeks after the defeat of his country, ‘The tragedy of the German people consists in the fact that they obeyed a band of criminals . . . The German working class and the productive parts of the population failed before history.’

This was more than Adenauer or most West German politicians were willing to concede, at least in public. But Ulbricht, like the Soviet authorities to whom he answered, was less interested in extracting retribution for Nazi crimes than in securing Communist power in Germany and eliminating capitalism. As a consequence, although denazification in the Soviet zone actually went further in some instances than it did in the West, it was based upon two misrepresentations of Nazism: one integral to Communist theory, the other calculatedly opportunistic.

It was a Marxist commonplace and Soviet official doctrine that Nazism was merely Fascism and that Fascism, in turn, was a product of capitalist self-interest in a moment of crisis. Accordingly, the Soviet authorities paid little attention to the distinctively racist side of Nazism, and its genocidal outcome, and instead focused their arrests and expropriations on businessmen, tainted officials, teachers and others responsible for advancing the interests of the social class purportedly standing behind Hitler. In this way the Soviet dismantling of the heritage of Nazism in Germany was not fundamentally different from the social transformation that Stalin was bringing about in other parts of central and eastern Europe.