Practically Perfect (25 page)

Read Practically Perfect Online

Authors: Dale Brawn

A little over a day after being charged with the murder of Sydney Petrie, Pavlukoff was flown back to Vancouver. Though his arrival was greeted with considerable anticipation by some British Columbia residents, his presence on the flight went unnoticed by fellow travellers. When reporters asked passengers what it was like sitting with Pavlukoff, most responded with “Who’s he?”

[25]

The same could not be said for those waiting on the ground. Even though the authorities tried to keep the timing of Pavlukoff’s return a secret, a large group of reporters waited in the airport administration building for a glimpse of the elusive bank robber. A Criminal Investigation Bureau superintendent warned photographers that if they attempted to take any pictures their cameras would be confiscated. The officer said that he planned to put Pavlukoff in a police lineup, and he did not want to give defence counsel possible grounds for calling the identification into question. He need not have worried. After other passengers disembarked the Trans-Canada Airlines North Star Pavlukoff stepped out of the aircraft directly into a police car waiting on the tarmac.

Shortly after the killer arrived at the police station where he was to be held pending his preliminary hearing and trial, his mother walked in. Dressed in an inexpensive, well-worn smock with a large bandana tied around her head, the distraught woman fought back tears as she was taken upstairs to speak with her son. Nearly an hour later she descended, her face buried in a handkerchief and her body wracked with emotion. She said that during her son’s flight from the law she seldom ventured from her home, and was nearly paralyzed with worry. “I am sorry I am so nervous,” she said, “but every time there is a knock on the door it is a blow against my heart. I may seem alive but inside I am only a shell.”

[26]

The first bit of good news Pavlukoff had heard for some time was that Thomas Francis Hurley, one of Vancouver’s most experienced criminal lawyers, was going to represent him. The day following his return to British Columbia the criminal and his counsel appeared before a police magistrate. Hurley made clear what his defence strategy would be. “I would judge that the question of identification might be one of the vital points in this case. For that reason I would ask for the exclusion of any person … who is a possible Crown witness.”

[27]

After two brief appearances in city police court Pavlukoff was remanded for a preliminary hearing, where the Crown was required to show that it had sufficient evidence against the accused to proceed to trial. The preliminary got off to a rough start, at least for Pavlukoff. Instead of leaving the courtroom when the fugitive entered, witnesses were told by the Crown to remain seated. As soon as Hurley realized what happened, he objected.

The Crown was unapologetic. “I wanted these witnesses here to get a look at the accused and I told them to remain in court until he was called.” In an admission that seemed to undermine the identification strategy of the defendant, the prosecutor admitted that “It was the only way of identifying the accused. The accused was offered a lineup to avoid this situation and he refused.” Over the protests of Hurley, the magistrate allowed the tainted identification in. “Don’t lecture me, Mr. Hurley. I want to get to the facts.”

[28]

One of the first pieces of evidence that went directly to the issue of identification was a moth-eaten hat found near the clothes thrown away by Pavlukoff during his escape. The dark blue fedora, bearing the initials “W.P.”, was identified by lead detective Arthur Stewart. Shortly after receiving it the detective testified that he was also given a man’s suit jacket and vest. From the markings on the clothing he discovered where the suit was made, and a day after the robbery officers interviewed the tailor who made the garments. In one of his measurement books they found Pavlukoff’s name, and attached to his fitting information was a piece of cloth matching that of the suit jacket.

According to the detective, a week after he talked to the tailor he received from Adam Tootell a pair of black shoes and a blue shirt. The officer noted that there were no heels on either shoe, and that one was broken near the heel, while the other looked as though it had been worn without a heel for some time. However poorly he might have been dressed on August 25, 1947, Pavlukoff was a different man during his two-day preliminary hearing. The thirty-nine-year-old wore a new grey, double-breasted suit, rust-coloured sport shirt, and a brightly coloured tie. Evident on each of his new brown shoes was a heel.

Nine people were in the bank when it was robbed, not counting the murdered manager. Of those who testified during the preliminary, four said Pavlukoff did not look like the bank robber, two said he resembled the killer, and two, one of whom was the wife of a Vancouver police detective, were certain he was the man who committed the murder. That was good enough for Magistrate Mackenzie Matheson, and Pavlukoff was committed for trial. It got underway two months later, presided over by a former provincial attorney-general.

In and out of court Mr. Justice Alexander Malcolm Manson was an outspoken, opinionated, abrasive individual, accused by contemporaries of making up his own law as he went along. In the quarter of a century he sat on the bench, more of his judgments were overturned on appeal than those of any other British Columbia judge. A few years after the Pavlukoff trial, Manson spoke as if he was proud of his less than sterling reputation. “As a judge I broke all the rules. Some think it is the sole duty of the court to protect the accused. But it is also its duty to see that society is protected.”

[29]

He seemed almost whimsical when he lamented that “The rock pile has gone and the preachers have done away with hell”

[30]

It did not take long for Pavlukoff to complain about Manson’s conduct on the bench. After one particularly heated exchange between his lawyer and the judge, Pavlukoff became infuriated. Perhaps sensing his fate, the bank robber jumped to his feet. “Your lordship, I found your behavior very disgusting and you seemed to have formed an opinion already as to my guilt. Not only is my life at stake, but my mother is at home sick, and before you kill her you will have to chain me to this box to keep me here.”

[31]

Justice Manson’s response gave some credence to Pavlukoff’s complaint about bias. “Fortunately for you, the matter is in the hands of the jury — in the hands of the jury and not in my hands.”

[32]

After a week-long trial, and a difference of opinion between several Crown witnesses over whether Pavlukoff was the bank robber, it took a jury just one hour to find the career criminal guilty of Petrie’s murder, and even less time for Manson to sentence him to be hanged. Until he was, Pavlukoff should have been confined in one of the Oakalla Prison Farm’s death row cells. But because his lawyers filed an appeal on his behalf, the bank robber was not regarded as a condemned prisoner. Until that proceeding was finished, he was kept in a section of the prison reserved for those awaiting trial. As a result, he had more privacy than he would have had on death row. He also had access to other prisoners, and contraband.

The beginning of the end for the convicted killer started mid-afternoon on Wednesday, July 8, 1953. After a five-day hearing the provincial Court of Appeal refused his request for a new trial, and one of Pavlukoff’s lawyers drove from the courthouse directly to Oakalla. According to the lawyer, his client took the news that he was to be hanged three weeks later without emotion, but seemed pleased Hurley was going to try to take his appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada.

Rules for those about to be executed at Oakalla were relatively relaxed, and Pavlukoff somehow managed to obtain a small knife. Within minutes of learning that the British Columbia Court of Appeal had denied his application for a new trial, the life-long criminal plunged the knife directly into his heart.

Rules for those about to be executed at Oakalla were relatively relaxed, and Pavlukoff somehow managed to obtain a small knife. Within minutes of learning that the British Columbia Court of Appeal had denied his application for a new trial, the life-long criminal plunged the knife directly into his heart.

Courtesy of Vancouver Sun.

In an ironic twist of fate, the bank robber was the only person in the prison who knew that his appeal had been rejected. Because of that, instead of being taken directly from his meeting to death row, Pavlukoff was returned to his holding cell. In anticipation of his appeal failing, Pavlukoff somehow obtained a small knife, and removed its handle and sharpened its blade. Where he hid the dagger was never determined, but ten minutes after learning that he was to be executed, the killer placed the point of the knife directly over his heart, then plunged the blade into his chest. Twenty-nine minutes later he was dead.

Hugh Christie, Oakalla’s warden, an outspoken opponent of capital punishment, was deeply distressed by the suicide. But as he said later, there was likely no way his officers could have prevented it.

Manual searches of prisoners are conducted as frequently as once a day. But this was a weapon so small that it could be concealed easily. Pavlukoff may well have concealed it in his mattress. We should have found the knife, but unfortunately we didn’t. When a man makes up his mind to kill himself, it’s pretty hard to stop him. In any event, it is primarily our fault, because we are supposed to be on the lookout for such things.

[33]

Christie said he could not help but to feel that Pavlukoff pondered how to kill himself for a long time before he actually committed the deed. “The precision with which he plunged the blade between two ribs and directly into the heart would indicate that he had spent some time in study. Or else he is just lucky.”

[34]

9

Pictures on the Dash

Owen “Mickey” Feener

Mickey Feener may have been a high-functioning moron in life, but in death he is the poster child of serial killers. Abandoned as a young man by parents who showed him neither love nor guidance, he married a fifteen-year-old from a similar background, murdered three women infatuated with his good looks and way with words, and did just about everything he could to be caught, short of actually turning himself in to the authorities. He killed on impulse, left his victims where they died, and in each murder was identified as the last person seen with the person he beat to death. Yet despite all this, it took police a year and a half to catch him, and even then they succeeded only because he was driving the flashy red sports car of one of his victims, his name prominently written across its hood with masking tape.

Owen Maxwell Feener was born in Bridgewater, Nova Scotia, in 1937, and from the beginning to the end of the eight years he lived with his parents he was unloved and unwanted. His father was an alcoholic, and Feener was mentally challenged. Add epilepsy to that and you have a child with more than a few problems. Things got worse when Feener was shot in the head and spent three months in hospital. Handed off by his parents to social services, he took his problems with him into foster care. Over the next three years he proved too much to handle, and after being classified as “mentally retarded,” he was committed to the Nova Scotia Training School. Feener entered the Truro facility when he was eleven, and left five years later. He could have left earlier, but his mother advised the local Children’s Aid Society that she was not prepared to take him back. When he turned sixteen Feener left the school, lonesome, frightened, and absolutely on his own. Not surprisingly, he turned to crime. He was first sentenced to three months in jail for stealing a rifle and hunting knife, and then to a year in reformatory for a couple of auto thefts. As soon as he was released Feener bought himself a car, and for the next three years drove without a licence, worried he was not smart enough to pass a driving test.

Feener was twenty when he married a girl five years his junior. She too came from a troubled background, and before meeting Feener was in and out of trouble with the law. Two years after they married the couple became parents to a daughter, and moved from Kirkland Lake, where Feener was working, back to Nova Scotia. There the relationship came to an abrupt end, in no small part because Feener started an affair with his wife’s sister.

My wife accused me of shacking up with her sister. I tried to explain, but no good. That’s when our marriage broke up. I then accepted her sister…. Well, that didn’t last either — well, my wife wanted me back but from then on she got herself in one mess after another. Yes — other men. I then left her for good.

[1]

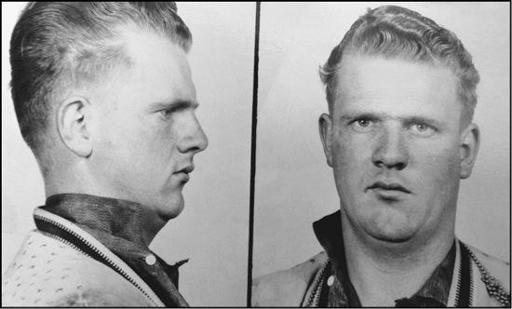

Mickey Feener may not look it in this photo, but in the 1950s he was quite the lady’s man. He was hanged for murdering two women, and confessed to killing a third. He taped photos of his victims to the dash of his car, along with the pictures of five other women. Although investigators were fairly certainly he killed the unidentified women, Feener kept his mouth shut right to the end.

Mickey Feener may not look it in this photo, but in the 1950s he was quite the lady’s man. He was hanged for murdering two women, and confessed to killing a third. He taped photos of his victims to the dash of his car, along with the pictures of five other women. Although investigators were fairly certainly he killed the unidentified women, Feener kept his mouth shut right to the end.

Courtesy of Library and Archives Canada.