Practically Perfect (27 page)

Read Practically Perfect Online

Authors: Dale Brawn

Before the year was out Toronto lawyer Hugh Latimer agreed to defend Feener against a murder his client freely admitted committing. Latimer quickly launched a motion for a new preliminary hearing, arguing that because his client was not represented at his first hearing, he was effectively denied the right to cross-examine his accusers. A superior court judge agreed, and another preliminary was convened. For the second time Feener was committed to stand trial. It started on March 6, and lasted three days. Key for the defence was the testimony of two psychiatrists from the North Bay Mental Hospital, whose reports were actually prepared at the request of the Crown. The first of the two doctors said that in his opinion Feener “was in an epileptic twilight state at the time of his crime. An epileptic twilight state is a temporary insanity that clears up after some time but has a tendency to recur.… Mr. Feener has been an epileptic for many years.”

[11]

As evidence, the doctor pointed to his dreamlike state of mind, “the explosive outburst of blind destructive aggressiveness, the loss of consciousness, and the consequent well circumscribed amnesia for a considerable part of the event.”

[12]

The second psychiatrist said that after drinking a large quantity of alcohol, Feener had a seizure, and during it he killed Chouinor. There was, he said, no evidence of premeditation.

Latimer did not call Feener as a witness, but in his summation spoke at length of his client’s troubled background.

My one concern in this matter is that an injustice should not be done to a young man, who through an accident of birth was not equipped, mentally and emotionally, to properly look after himself. My client had no motive when he killed this girl of high moral standards. Not sex. Not money. I say the hand that struck the blow was not ruled by the brain.

[13]

The Crown Attorney prosecuting Feener acknowledged that the accused had a troubled background, but argued that he was still criminally responsible for his actions. Referring to Feener, he said. “He had a bad upbringing, an abnormal personality and undeveloped mentality, but he is not an imbecile and not an idiot.”

[14]

Members of the all male jury agreed with the prosecutor, and it took them just fifteen minutes to return with a verdict of guilty. The triple killer was sentenced to hang three months and one week later. Before that happened, however, Latimer asked the Ontario Court of Appeal to throw out his client’s conviction. They were not prepared to do that, and one month before he was to hang, Feener’s remaining hope was an application for clemency.

The federal cabinet met on June 8, to discuss whether to grant a commutation. Some members pointed to evidence that Feener acted like an insane man during his assault on Chouinor, and they suggested that he should be kept in custody for the rest of his life. They felt the murder he was convicted of committing was neither planned nor deliberate, and the method used to kill Chouinor was far from rational.

[15]

These cabinet members might also have pointed to an amendment to the law dealing with capital murder, which was about to come into effect. It would change the definition of the crime, so that in the future capital murder had to be planned and deliberate, two things Feener’s was not.

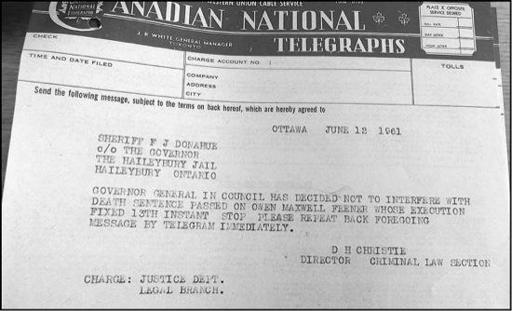

To ensure that condemned prisoners did not act up or become violent, the federal government refused to inform death row inmates if they were going to be executed, or have their sentence commuted to life imprisonment. Telegrams like the one received by Mickey Feener typically arrived just hours before a prisoner was scheduled to be hanged.

To ensure that condemned prisoners did not act up or become violent, the federal government refused to inform death row inmates if they were going to be executed, or have their sentence commuted to life imprisonment. Telegrams like the one received by Mickey Feener typically arrived just hours before a prisoner was scheduled to be hanged.

Courtesy of Library and Archives Canada.

A majority in the cabinet of Conservative Prime Minister John Diefenbaker, however, believed that if Feener was clever enough to try and cover up his crime, and was able to attract women all over eastern Canada, he was sane enough to hang. The majority even rejected the arguments in favour of clemency advanced by Georges Vanier, the country’s governor-general. Vanier pointed out that under the

Criminal Code

amendments about to be passed in Parliament, Feener could not be hanged; and, he added, because Feener was by everyone’s admission a moron, he should not be hanged.

[16]

But hanged he was. No doubt members of the federal cabinet, like the jurors who found him guilty at trial, were influenced by a vision of the photos taped to the dash of the killer’s car. The three women identified were all murder victims; the fate of the other five remains unknown.

Owen Maxwell Feener was hanged in the courtyard of the Haileybury Jail in northeastern Ontario. He died at 1:03 a.m. on June 13, 1961. Whatever concern he may have had for what was to come did not affect his appetite, and he ate with gusto a last meal of steak and French fries. The only thing that seemed to bother him was a sense of guilt over what he had done to Dolly Woods. Two hours before he was to be executed, Feener asked if the sheriff could be summoned to his cell. When the sheriff arrived Feener handed him a scrap of paper, on which he had scribbled a confession. “I’m going to roast in hell,” he said. “I’d just as soon do it with a clear conscience.”

[17]

Wherever Feener ended up, it was without his eyes. Just before he began his death walk he decided to make a last gesture: he asked that his eyes be given to an eye bank. His hope, he told those standing around him, was that “the poor devil who gets them trains himself to look at something besides skirts.”

[18]

The sad and pathetic story of Mickey Feener did not end with his execution in 1961. When her father was put to death, Feener’s daughter was a little over two years old. Life was tough for her and her mother, and it got tougher. The daughter was eleven when her only parent gave her away, her mother more committed to a new husband and three new children than she was to the child of a killer. The young girl remembers standing in a phone booth, asking why she was being abandoned.

I felt I was not meant to have any family. And so that is what happened. The mother, the husband and the three other children went on to live their lives and not even take a second to wonder if the little girl that was given away was even alive. It is amazing how the life of my mother [who died during surgery in 2010] and my father may have influenced the choices and the things that occurred in my life. Choosing a wrong partner, going the wrong way and making bad decisions. Having bad things thrust upon me.

[19]

Was this, she wondered, her destiny. “I would never understand why.”

10

Skeletons Resurface

It is sometimes said that the secrets of our past are sooner or later bound to haunt us. That was certainly the case for the men whose stories are told in this chapter. All three murdered and escaped detection for a considerable time, until the bodies of their victims resurfaced. Strictly speaking, only in one case did a skeleton actually return to the surface; two of the killers simply left their victims where they were killed.

John Munroe:

Nobody Asked About Mother and Daughter

The young architect was anything but subtle. He met his lover at a public event, he courted her in full view of the community, he showed up at her home every Sunday, she gave their baby girl his surname, and virtually everyone who knew him regularly saw the couple out and around Saint John, New Brunswick. When the married father of two (now three) decided to murder the mother of his illegitimate child, he hired a coach and coachman, and twice drove her to the spot where what remained of the mother and child eventually were found. And despite making absolutely no effort to hide his cruel deed, he very nearly got away with the murders.

John Munroe was born in Ireland in 1839, one of three children of a well-to-do carpenter. When the family immigrated to Canada in the 1840s, they settled in Saint John. John worked in his father’s lumberyard after school, and it seemed almost inevitable that he would go into the building business. Munroe was ten when his future lover was born. Her father was also a carpenter, but unlike John, Sarah Margaret Vail had anything but an easy life. Her mother died a few months after she was born, and she and her sister made do with whatever was at hand.

Munroe was twenty-three when he married Annie Potts, and before a year passed the couple became the parents of their first child. Three years later the young married man met Sarah at a community event in Caledon, on the outskirts of Saint John. By the time Munroe and his wife had their second boy, Munroe and Vail were lovers. On February 4, 1868, Sarah gave birth to Munroe’s baby, a girl she named Ella May Munroe. The affair was public knowledge, except perhaps to Annie.

In 1867 Vail’s father died, leaving her the family home. Sarah sold it the following year for $500, a small fortune in nineteenth-century New Brunswick. It seemed only natural that she would turn to her lover for advice about how to invest the money. That was a mistake. Munroe later said he first thought of murdering Sarah and their daughter two days before he committed the crime. With the benefit of hindsight, it is almost certain that he had murder on his mind from the day she sold her home; which perhaps explains why it was then that he purchased a .22 calibre revolver. It was also about this time that he left a letter with a friend in Boston. The letter was addressed to Vail’s sister, and was ostensibly written by Sarah. In it Sarah wrote that she had run off with a man she was about to marry, and asked that no one worry about her. The letter was the first step in an ill-conceived plot to murder its alleged author.

Once Vail sold her residence, her life-clock rapidly began winding down. Two weeks before she was murdered, Munroe told Vail that he and a few associates from Saint John were going on a junket to Boston, where they intended to mix a little pleasure with business. When Sarah insisted that she accompany her lover, Munroe obliged her. The pair returned on Friday, October 23, and Vail checked into the Brunswick Hotel as Mrs. Clarke. She informed the proprietor that her husband would soon be joining her and their young girl, and the following day her trunks arrived from the boat. On Monday Munroe showed up in a hired coach. He, Sarah, and Ella May then went for a drive into the countryside north of Saint John. When they returned, Vail checked into the Union Hotel, again as Mrs. Clarke, and Munroe made arrangements for her trunk to be brought from the Brunswick.

Three days later Vail and her daughter were to have left Saint John for Boston, but the day was wet and stormy, and Munroe persuaded Sarah to postpone her trip for a few days. Munroe, on the other hand, did not change his own plans. He and his wife spent the next day and a half on a return trip to Fredericton, New Brunswick. He later said that it was on this trip that he began thinking about murdering Vail and his baby. He kept thinking about how desolate the road was when they drove into the countryside, and became convinced that it would be the perfect place to put an end to the complications his lover brought into his life. With murder in mind, Munroe hired the same coach and driver he retained earlier in the week, and on Saturday he picked up his lover. He also told a number of people that Mrs. Clarke would be leaving for Boston on the following Tuesday, and made arrangements for her trunk to be taken to the steamer

New England

.

When the Munroe party of three reached that part of the road where they stopped the previous Monday, he told the coachman that Mrs. Clarke and her baby would walk from there to the home of friends. He was going to accompany them part way, and would catch up with the driver at a hotel they just passed. With that Munroe and his travelling companions got out and began walking down the deserted road. About an hour later a clearly excited Munroe hurried into the hotel where his driver was eating, and said they were to leave at once for Saint John. Once he got back to the city Munroe put Vail’s trunks on the steamer, and for the next year they sat unclaimed in a Boston warehouse.

Despite conducting his affair in full view of almost everyone who knew him, no one seemed to notice that Munroe’s lover and her baby were missing. Vail’s sister certainly did not care. She and Sarah had a falling out over their father’s estate, and there was no one else who might have worried even if they knew the mother and daughter were missing. And indeed, for ten months and twelve days it appeared that John Munroe had committed the perfect murder. Then, on September 12, 1869, a group of berry pickers stumbled across two skeletons, one apparently that of an adult, the other of an infant.

For the next two days dozens of local residents made their way through a hundred feet of bush to see the remains. One of them, William Douglas, was part of a group whose members picked and probed the skeletons to see what they could find. He later recalled that a woman standing near him “took a stick and pulled up a bunch of hair, all braided, then she stuck the stick down again in the same place and turned up a part of a bonnet. I turned over the skull, and out of it ran brains and stuff, making a great smell. There was a little shoe there too, and a stocking in it; there was some kind of corruption in it, which, when the shoe was turned over, ran out, making a bad smell.”

[1]

A considerable amount of braided hair was attached to the skull, a sizeable curl on one side, styled in what then was referred to as a waterfall. Lying near the skull were pieces of a child’s smock and a tiny shoe. To even the uneducated eye it was obvious that the remains had been eaten by animals.