Pride and Prejudice and Zombies (11 page)

Read Pride and Prejudice and Zombies Online

Authors: Seth Grahame-Smith

Tags: #Humor & Entertainment, #Humor, #Parodies, #Satire, #Literature & Fiction, #British & Irish, #Humor & Satire, #Genre Fiction, #Horror, #Mashups, #Humorous, #Women's Fiction, #Sisters, #Reference, #Romance, #Historical, #Regency, #Romantic Comedy, #Comedy, #General Humor

“Well, I suppose we had ought to take all of their heads, lest they be born to darkness,” she said.

Mr. Bingley observed the desserts his poor servants had been attending to at the time of their demise—a delightful array of tarts, exotic fruits, and pies, sadly soiled by blood and brains, and thus unusable.

“I don’t suppose,” said Darcy, “that you would give me the honour of dispensing of this unhappy business alone. I should never forgive myself if your gown were soiled.”

“The honour is all yours, Mr. Darcy.”

Elizabeth thought she detected the slightest smile on his face. She

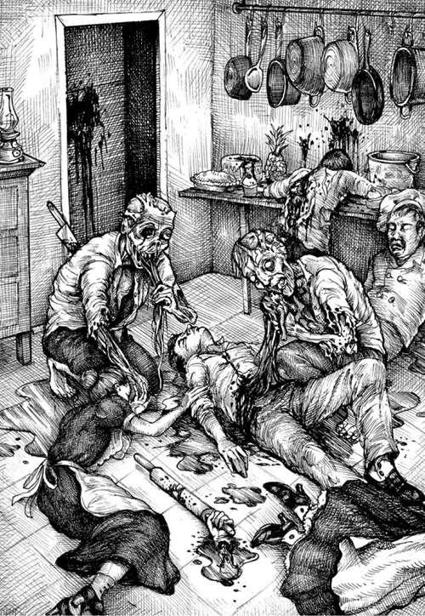

“TWO ADULT UNMENTIONABLES—BOTH OF THEM MALE—BUSIED THEMSELVES FEASTING UPON THE FLESH OF THE HOUSEHOLD STAFF.”

watched as Darcy drew his blade and cut down the two zombies with savage yet dignified movements. He then made quick work of beheading the slaughtered staff, upon which Mr. Bingley politely vomited into his hands. There was no denying Darcy’s talents as a warrior.

“If only,” she thought, “his talents as a gentleman were their equal.”

When they returned to the ball, they found the spirits of the others very much disturbed. Mary was entertaining them at the pianoforte, her shrill voice testing the patient ears of all present. Elizabeth looked at her father to entreat his interference, lest Mary should be singing all night. He took the hint, and when Mary had finished her second song, said aloud:

“That will do extremely well, child. You have delighted us long enough. Let the other young ladies have time to exhibit.”

To Elizabeth it appeared that, had her family made an agreement to embarrass themselves as much as they could during the evening, it would have been impossible for them to play their parts with more success.

The rest of the evening brought her little amusement. She was teased by Mr. Collins, who continued most perseveringly by her side, and though he could not prevail on her to dance with him again, he put it out of her power to dance with others, by using his thick middle to hide her from view. In vain did she offer to introduce him to any young lady in the room. He assured her, that he was perfectly indifferent to it; that his chief object was by delicate attentions to recommend himself to her and that he should therefore make a point of remaining close to her the whole evening. There was no arguing upon such a project. She owed her greatest relief to her friend Miss Lucas, who often joined them, and good-naturedly engaged Mr. Collins’s conversation to herself.

She was at least free from the offense of Mr. Darcy’s further notice; though often standing within a very short distance of her, quite disengaged, he never came near enough to speak. She felt it to be the probable consequence of her allusions to Mr. Wickham, and rejoiced in it.

When at length they arose to take leave, Mrs. Bennet was most pressingly civil in her hope of seeing the whole family soon at Longbourn, and addressed herself especially to Mr. Bingley, to assure him how happy he would make them by eating a family dinner with them at any time, without the ceremony of a formal invitation. Bingley was all grateful pleasure, and he readily engaged for taking the earliest opportunity of waiting on her, after his return from London, whither he was obliged to go the next day for a meeting of the

Society of Gentlemen for a Peaceful Solution to Our Present Difficulties

, of which he was a member and patron.

Mrs. Bennet was perfectly satisfied, and quitted the house under the delightful persuasion that she should see her daughter settled at Netherfield, her weapons retired forever, in the course of three or four months. Of having another daughter married to Mr. Collins, she thought with equal certainty, and with considerable, though not equal, pleasure. Elizabeth was the least dear to her of all her children; and though the man and the match were quite good enough for her, the worth of each was eclipsed by Mr. Bingley and Netherfield.

CHAPTER 19

THE NEXT DAY opened a new scene at Longbourn. Mr. Collins made his declaration in form. On finding Mrs. Bennet, Elizabeth, and one of the younger girls together, soon after breakfast, he addressed the mother in these words:

“May I hope, madam, for your interest with your fair daughter Elizabeth, when I solicit for the honour of a private audience with her in the course of this morning?”

Before Elizabeth had time for anything but a blush of surprise, Mrs. Bennet answered instantly, “Oh dear! Yes—certainly. I am sure Lizzy will be very happy—I am sure she can have no objection. Come, Kitty, I want you upstairs.” And, gathering her work together, she was hastening away, when Elizabeth called out:

“Dear madam, do not go. I beg you will not go. Mr. Collins must excuse me. He can have nothing to say to me that anybody need not hear. I am going away myself.”

“No, no, nonsense, Lizzy. I desire you to stay where you are.” And upon Elizabeth’s seeming really, with vexed and embarrassed looks, about to escape, she added: “Lizzy, I

insist

upon your staying and hearing Mr. Collins.”

Mrs. Bennet and Kitty walked off, and as soon as they were gone, Mr. Collins began.

“Believe me, my dear Miss Elizabeth, that your modesty adds to your other perfections. You would have been less amiable in my eyes had there

not

been this little unwillingness; but allow me to assure you, that I have your respected mother’s permission for this address. You can hardly doubt the purport of my discourse, for however preoccupied you might be with hastening the Devil’s retreat—for which I earnestly applaud you—my attentions have been too marked to be mistaken. Almost as soon as I entered the house, I singled you out as the companion of my future life. But before I am run away with by my feelings on this subject, perhaps it would be advisable for me to state my reasons for marrying—and, moreover, for coming into Hertfordshire with the design of selecting a wife, as I certainly did.”

The idea of Mr. Collins, with all his solemn composure, being run away with by his feelings, made Elizabeth so near laughing, that she could not use the short pause he allowed in any attempt to stop him further, and he continued:

“My reasons for marrying are, first, that I think it a right thing for every clergyman to set the example of matrimony in his parish. Secondly, that I am convinced it will add very greatly to my happiness; and thirdly, that it is the particular advice and recommendation of the very noble lady whom I have the honour of calling patroness. It was but the very Saturday night before I left Hunsford that she said, ‘Mr. Collins, you must marry. A clergyman like you must marry. Choose properly, choose a gentlewoman for my sake; and for your own, let her be an active, useful sort of person, not brought up high, but able to make a small income go a good way. This is my advice. Find such a woman as soon as you can, bring her to Hunsford, and I will visit her.’ Allow me, by the way, to observe, my fair cousin, that I do not reckon the notice and kindness of Lady Catherine de Bourgh as among the least of the advantages in my power to offer. You will find her powers of combat beyond anything I can describe; and your own talents in slaying the stricken, I think, must be acceptable to her, though naturally, I will require you to retire them as part of your marital submission.”

It was absolutely necessary to interrupt him now.

“You are too hasty, sir,” she cried. “You forget that I have made no answer. Let me do it without further loss of time. Accept my thanks for the compliment you are paying me. I am very sensible of the honour of your proposals, but it is impossible for me to do otherwise than to decline them.”

“I am not now to learn,” replied Mr. Collins, “that it is usual with young ladies to reject the addresses of the man whom they secretly mean to accept, when he first applies for their favour; and that sometimes the refusal is repeated a second, or even a third time. I am therefore by no means discouraged by what you have just said, and shall hope to lead you to the altar ere long.”

“You forget, sir, that I am a student of Shaolin! Master of the seven-starred fist! I am perfectly serious in my refusal. You could not make

me

happy, and I am convinced that I am the last woman in the world who could make

you

so. Nay, were your friend Lady Catherine to know me, I am persuaded she would find me in every respect ill qualified for the situation, for I am a warrior, sir, and shall be until my last breath is offered to God.”

“Were it certain that Lady Catherine would think so,” said Mr. Collins very gravely, “but I cannot imagine that her ladyship would at all disapprove of you. And you may be certain when I have the honour of seeing her again, I shall speak in the very highest terms of your modesty, economy, and other amiable qualification.”

“Indeed, Mr. Collins, all praise of me will be unnecessary. You must give me leave to judge for myself, and pay me the compliment of believing what I say. I wish you very happy and very rich, and by refusing your hand, do all in my power to prevent your being otherwise.” And rising as she thus spoke, she would have quitted the room, had Mr. Collins not thus addressed her:

“When I do myself the honour of speaking to you next on the subject, I shall hope to receive a more favourable answer than you have now given me. I know it to be the established custom of your sex to reject a man on the first application.”

“Really, Mr. Collins,” cried Elizabeth, “you puzzle me exceedingly. If what I have hitherto said can appear to you in the form of encouragement, I know not how to express my refusal in such a way as to convince you of its being one.”

“You must give me leave to flatter myself, my dear cousin, that your refusal of my addresses is merely words of course.”

To such perseverance in wilful self-deception Elizabeth would make no reply, and immediately and in silence withdrew; determined, if he persisted in considering her repeated refusals as flattering encouragement, to apply to her father, whose negative might be uttered in such a manner as to be decisive, and whose behavior at least could not be mistaken for the affectation and coquetry of an elegant female.

CHAPTER 20

MR. COLLINS WAS NOT left long to the silent contemplation of his successful love; for Mrs. Bennet, having dawdled about in the vestibule to watch for the end of the conference, no sooner saw Elizabeth open the door and with quick step pass her towards the staircase, than she entered the breakfast-room, and congratulated both him and herself in warm terms on the happy prospect of their nearer connection. Mr. Collins received and returned these felicitations with equal pleasure, and then proceeded to relate the particulars of their interview.

This information startled Mrs. Bennet; she would have been glad to be equally satisfied that her daughter had meant to encourage him by protesting against his proposals, but she dared not believe it, and could not help saying so.

“But, depend upon it, Mr. Collins,” she added, “that Lizzy shall be brought to reason. I will speak to her about it directly. She is a very headstrong, foolish girl, and does not know her own interest—but I will

make

her know it.”

Hurrying instantly to her husband, she called out as she entered the library, “Oh! Mr. Bennet, you are wanted immediately; we are all in an uproar. You must come and make Lizzy marry Mr. Collins, for she vows she will not have him.”

Mr. Bennet raised his eyes from his book as she entered, and fixed them on her face with a calm unconcern.

“I have not the pleasure of understanding you,” said he, when she had finished her speech. “Of what are you talking?”

“Of Mr. Collins and Lizzy. Lizzy declares she will not have Mr. Collins, and Mr. Collins begins to say that he will not have Lizzy.”

“And what am I to do on the occasion? It seems a hopeless business.”

“Speak to Lizzy about it yourself. Tell her that you insist upon her marrying him.”

“Let her be called down. She shall hear my opinion.”

Mrs. Bennet rang the bell, and Miss Elizabeth was summoned to the library.

“Come here, child,” cried her father as she appeared. “I have sent for you on an affair of importance. I understand that Mr. Collins has made you an offer of marriage. Is it true?” Elizabeth replied that it was.

“Very well—and this offer of marriage you have refused?”

“I have, sir.”

“Very well. We now come to the point. Your mother insists upon your accepting it. Is it not so, Mrs. Bennet?”

“Yes, or I will never see her again.”

“An unhappy alternative is before you, Elizabeth. From this day you must be a stranger to one of your parents. Your mother will never see you again if you do

not

marry Mr. Collins, and I will never see you again if you

do

; for I shall not have my best warrior resigned to the service of a man who is fatter than Buddha and duller than the edge of a learning sword.”

Elizabeth could not but smile at such a conclusion of such a beginning, but Mrs. Bennet, who had persuaded herself that her husband regarded the affair as she wished, was excessively disappointed.