Project X (9 page)

“If you fell asleep on your back and it was raining hard enough, do you think you'd drown?” I ask him.

“No,” he goes.

“I think you would drown,” I tell him.

My dad eats his carrot. “You seem a little down,” he goes.

My hands are holding up my chin. I let my head slip through them until they finally have to grab my hair.

“Your mother tells me the Nightrider's run afoul of the law,” he goes.

“Yeah,” I go.

“He's a misunderstood figure, there's no doubt about that,” my dad goes.

I make a sound like a horse.

It makes my dad laugh. “Only in junior high can you be the object of awe

and

derision,” he goes.

“What's that mean?” I ask.

He shrugs. He looks at his beer like he admires it. “Economics humor,” he goes.

“Doesn't sound like economics,” I tell him. I still haven't turned around from the window.

Gus is in the den singing to himself and playing with a toy that needs batteries and has no batteries. Lately he's been going around the house butchering one of his favorite songs from a kid's show he watches. The song's called “We All Sing with the Same Voice.” He sings it “We all sing with the same boys.”

“Remember that thing you hung on the Christmas tree?” my dad goes. He says it like he doesn't need an answer, and I don't say anything. It's raining even harder.

“It's like blue out,” I finally go.

What he's talking about was last year when my English teacher told us at the beginning of a class that she'd just read the greatest short story in the history of the English language. She held up the book and hugged it to her chest. We were like,

Please

.

She read the beginning of it in this hushed voice.

“I'm so moved,” this kid next to me whispered, and a few kids giggled.

There was one line that sounded right, though. I went up after class and asked if I could see it. It probably made her month.

The line was “Christmas came, childless, a festival of regret.” I copied it down while she stood there. She asked if I wanted to read the whole story, and I told her I'd get it out of the library.

When we were decorating, I put the line on a star-shaped piece of paper and hung it on the tree. “What the hell is

this

?” my dad said when he finally found it.

9

Flake had the idea to bury something we wrote in a box for people to find like years later. There's a word for it but I forget what it is. He said it had to be a good box to keep the water out so what we wrote wouldn't rot. He said to work on what we were going to put into it. I'd work on mine and he'd work on his. Then we'd put our stuff in together. We don't know where we're going to bury it yet, now that we can't use our fort under the underpass. He thought it would be funny to put it next to the flagpole in front of the school, but I thought people would see where the ground had been dug up. He thought we could do it so nobody could tell.

I have a pad I've been writing stuff in and hiding in a space above where my top drawer fits into my desk. There's nothing on the cover but on the first page I wrote PROJECT with a pair of crossbones underneath. They look like an X. On the second page I have a score sheet divided into days of the times that people haven't looked at me or talked to me or answered me at school. I make a crossbones for each one and put them in a column. I fill it out when I get home from school or, if Flake comes home with me, before I go to bed. Mondays are ahead of Thursdays for first place.

On the third page I have a drawing of these huge Gatling guns they use in Chinook and Huey gunships. They fire like eight million rounds per minute. After that I have a drawing of Gus in sunglasses that I think is funny. I did it when he fell asleep in my room and I was supposed to be watching him. After that I have some demon faces that I can never get right.

After that there's a lot I still need to write down. Like: What happens when you hate yourself?

What happens when you know you're

worse

than anybody else knows you are?

What happens when everything you touch turns to shit?

What happens when you feel sorry for yourself and then sit around feeling sorry for yourself for feeling sorry for yourself?

Poor kids or kids who can't walk or pick up anything and have to work a computer with like sticks in their teeth: we're lucky compared to them. We're whiners. We're babies.

We're good at reminding each other how pissed off we are and how nobody cares, not really. Sometimes one of us'll whack the other on the side of the head to remind him of what we have to do.

So when we get his dad's guns and go into the assembly and we see like some special-ed kid in one of those chairs, do we bail and come back later when we hope there's only going to be people we hate around? We need to make sure that once we're in, we can't be going, Hey, watch out for Tawanda, or Let's not get Mrs. Pruitt, let's get Ms. Meier.

Flake says nobody's going to be taking him alive and that he's not going to shoot himself, either. I don't think we have to decide about that yet.

We might get away.

After a sign-up sheet for achievement tests went around the homerooms last week, he had us get out his father's guns again when the house was empty and he squatted on the bed and had us hold the Kalashnikov and the carbine up over our heads. Here's

my

achievement tests, he said. Here's yours.

For the next fifty years, people who weren't anywhere around will swear they were right here when it happened. “So there I was, bullets flying.” Shit like that. It makes us wish they

were

here. Then we could shoot them and they'd get what they want: proof they're not bullshitters.

Flake gives me a 50 percent chance of wussing out. He says if I do he'll shoot me himself. “I'll shoot you, you fuck,” I tell him. It always makes him laugh.

He says to remember that out of everybody in the gym there's still only going to be two kinds of people: the ones who don't know anything about us, and the ones who don't want to know.

10

He hasn't given up on Matthew Sfikas. I can see his brain going, trying to figure something out. When I tell him again about my idea about waiting he goes, “I'll kick his ass now, and we can shoot him later.”

“How are you going to kick anybody's ass with two fingers like that?” I want to know.

“I'll use a shovel,” he goes. “I'll use a rake.”

“You can't use a shovel,” I go. “You can't use a rake.”

“What do you care?” he goes. “I'll use a chain saw if I want.”

He won't, though.

“So let's find him then,” I go. “Bring your rake.”

“You think I won't?” he asks.

But then we end up just sitting in his room, and he's in a bad mood for the rest of the day.

“Why don't you put bug powder in his milk?” I go. I'm looking at the booklet that comes with his Great Speeches CD. Something knocks me to the floor on my face, and he's jumping up and down on my back with his knees.

I scream for him to quit it when I can, but he doesn't and finally I'm able to twist around and get him on the side of the head with my fist. Once he's off I keep using my right hand and he blocks it with his arm but not completely because he's trying to protect his finger. He straight-arms me in the mouth with the heel of his palm. Then we both go nuts.

His mom runs upstairs and separates us. It takes her some time, and she ends up with a scratched face. We're screaming at each other and she's screaming at us. One of his fingers is bleeding through the bandage.

“Fucking maggot,” he keeps screaming.

“Suck me,” I scream back.

“

Stop

it,

both

of you,” his mom screams. We still won't stop trying to beat on each other, so finally she drags me downstairs by the collar. “Don't come back here, you fuck,” he yells down the stairs. “Fuck you,” I yell back up. “Stop it,” his mom yells, shaking me so hard that she almost breaks my neck. She shoves me out onto the driveway and slams the back door.

She calls my parents while I'm walking home.

“I hear you and the Nightrider thought you were in the Thunderdome,” my dad says when I walk in the door.

“I don't know what that means,” I go.

“Are you all right?” my mom wants to know. I look in the mirror in the bathroom. My teeth are bloody and there's dried blood on my chin and some on my shirt. My back hurts where he was jumping on it. My lip's cut up again. Otherwise I'm fine. I feel like I'm going to cry, but that's out of frustration.

“It's all right,” my mom says when she sees my face once I finally come back out of the bathroom. I stand there in the middle of the kitchen like I got a load in my pants. My dad knows enough not to say anything.

“Want me to help you with your face?” she goes.

“Yeah,” I go. And start crying.

“It's okay,” she goes. She comes over and puts her arms around me.

“Fucking asshole,” I go, barely able to understand myself. I hang on to her for a minute.

“Hey,” my dad says, about the language. My mom tells him to shush. Gus is up in their bedroom watching videos and misses the whole thing.

I don't call Flake or hear from him for a week. He wanders by in the hall a few times at school. I get up in the morning, get my stuff together and head for the bus. I come home, go up to my room and dump my stuff on the floor. I do homework. I do better than the teacher expected on a social studies quiz.

My dad asks a few days into this if I want to play catch. The next night my mom calls up the stairs that there's a special on about naval firepower.

After I'm supposed to be asleep I walk around the house without turning on the lights. I take the Bible out of their downstairs bookcase and read it in the afternoons. I think about copying down parts but never get around to it. I like Leviticus and Revelations. I look at the pictures in African Predators. There's one of a leopard that got ahold of a baboon. The baboon's face is being squeezed shut by the bite.

“So now you're not eating?” my dad asks after a while.

Gus comes into my room and sits with me sometimes, then goes out again.

“Can I tell you something?” my dad says, another time, at dinner.

“No,” I go.

Finally, after a week and a half, I call Flake's house. The phone rings and rings and no one picks up.

In the mornings when I look in the mirror to comb my hair it looks like I have two black eyes.

My dad sits there while I have breakfast. He asks how I'm sleeping. I tell him I have no idea.

Hermie starts hanging out with me before the homeroom bell rings in the morning. He doesn't say anything about Flake. At first he doesn't say much at all.

“Listen, you gotta help me get back at Budzinski,” he finally goes.

“Who

is

this kid?” I go.

He points across the playground but there's like forty kids where he's pointing.

It's about the third day he's been hanging around, and we're both watching other kids have fun. A bunch of them are seeing how many it takes to clog the tunnel slide for the grammar school. They're falling out and getting stuck and everybody's screaming.

He scratches his back through his SCREW THE SYSTEM shirt.

“You ever wash that?” I ask him.

“My mom does,” he goes. “You ever wash those?” he says about my pants.

Near the window where Flake and I broke in I can see the girl who was crying three straight days last week. She's creeping around trying to sneak up on a pigeon. The pigeon keeps walking just out of her reach.

“You don't look so good,” he goes. I make a face and he drops the subject.

Two other girls are standing there making fun of the one who's creeping around after the pigeon. Every so often she looks over when she doesn't think they're looking. She's the kind of girl who follows along with all the conversations and smiles whenever she gets noticed. The sun comes out and the whole playground gets warmer.

“So would you help me?” he goes.

“Help you what?” I go.

“With Budzinski,” he goes.

“I'm not gonna help you beat up some sixth-grader,” I tell him.

“I don't want you to help beat him up,” he goes. “I just need help with a plan.”

“A plan,” I go. “Just hide behind a bush and hit him with a stick.”

“That's a plan?” Hermie goes.

“He's a sixth-grader,” I go. “Take his candy. Push him down in the sandbox.”

This pisses him off so much he shuts up for a while.

“I went after him with a stick,” he finally goes.

“You went after him with a stick?” I ask him.

“He took it away and hit me with it.” He looks ashamed.

This is what my life has come down to. I'm talking to sixth-graders about who beat who with a stick.

Hermie's tearing up, just thinking about it.

“Hey, it happens,” I tell him.

“No it doesn't,” he goes. “Not to anyone else.”

“I get my ass kicked all the time,” I tell him. “Are you kidding?”

He wipes his face and looks at his feet. He has an expression like getting compared to me isn't a help.

The bell rings for homeroom.

“

Some

body's gotta do something,” he goes as we stand up and head inside. We get shoved aside by everybody who's more anxious than we are to get in.

“I'm gonna get the gun,” he tells me the next day before homeroom. “Let's see what he does then.”

“What are you talking about?” I ask.

“Let's see what he does then,” he goes.

“What, you're gonna get your dad's gun and

shoot

him?” I go. I have this whirling in my stomach. I even put my hand on it.

“They'll know they can't fuck with me,” he goes.

“Of course they can fuck with you,” I go. “You're like two feet tall.”

He looks out over the playground like it'd be hard to stop with just Budzinski.

“Don't talk stupid,” I tell him. I don't know what else to say.

“I'm not talking stupid,” he goes.

“It sure sounds like it,” I tell him.

“No it doesn't,” he goes.

Two fat girls are two steps down from us on the front stairs. “Which is better, an A or an A minus?” one goes.

“What're you

talking

about?” the other one goes.

“I got this,” Hermie tells me. He shows me a knife inside his backpack. It's one of those knives you use to clean fish.

“What are you doing?” I go. “Are you fucking nuts?” He puts the knife down at the bottom of his pack and pulls out one of his school folders. “Are you fucking nuts?” I ask him again. “Bringing that to school?”

He starts pulling papers out of the folder, looking for something, spreading everything out so he can see. Some slide down the steps.

I stop one that's about to blow away. “You can't just get a gun,” I tell him.

He keeps looking for whatever it is. He's not making much progress.

“You hear me?” I ask him.

“Leave me alone,” he goes. He's crying again. Then he slips and the whole folder dumps open. Assignments and worksheets slide down the cement. They're filled with X's and red marks. The homeroom bell rings. He's scrambling around trying to get everything before the stampede reaches the stairs. I help with some papers right around me. A kid who's running past doesn't see him bending down and decks him. They both go flying. It's a big hit with the kids who have a view of it.

I help him up and he shakes loose and gets the rest of his papers and carries them into the building in a mess under his arm.

He doesn't show up the next day once I'm off the bus and hanging around. That night it occurs to me while I'm patrolling the house that we could be in real trouble if this nimrod takes out a gun and waves it around at school. That could be the end of our plan. Though I don't even know if our plan is still on. This occurs to me while I'm sitting in the living room in the dark watching cars drive by down the street.

I get like one hour's sleep. The next morning I circle the playground, but Hermie's not there and neither is Flake.

In English we all have to sign a poster that covers a whole cabinet wall and says “English 8: In Our Own Words.” The last four sentences at the bottom are

I want to succeed in high school, but I know it will be a

challenge.

I am not a loser.

(Somebody's already crossed out the not.)

I will be a nobody to most and a somebody to a few.

In

8

th grade, I am a nervous student.

I find a clear spot and sign “F.U. Verymuch” so only I can read it. Bethany, the girl Flake was talking about, comes up to me after class in the hall and hands me a folded piece of pink paper. When she lifts her hand her wristwatch always slides down practically to her elbow. She's carrying a zebra-skin pencil case.

“What's this?” I go.

“It's for you,” she says, and her friends watch and giggle.

I read it on the way to math.

I'm pissed that I was excited there for a minute because a girl was giving me a note. I almost ball the thing up and throw it away, but I don't.

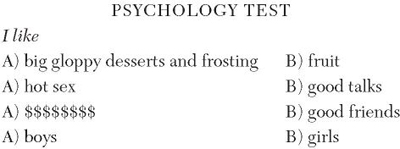

Bethany and her friends follow me while I'm reading. It makes me paranoid. I spend two periods thinking about what to do with it. Finally, since I'm alone again at lunch, I fill it out. I write “with” after “hot sex” and draw an arrow to “fruit.” I write “with” after “good talks” and draw an arrow to “big gloppy desserts.” I draw an arrow from “girls” to “$$$$$$$,” and just leave “boys” and “good friends” blank.

I give it back to her when I go to bus my tray. In line I can see her and her friends leaning over it like it's a treasure map.

“You are so weird,” she says to me later in the hall.

In seventh period the teacher's late and all the guys sitting around me are talking about hard-ons.

After school when I get home I call Flake again. This time he answers the phone.

“We got a problem,” I tell him after he says hello. He hangs up.

I look at the phone and beat on the cradle part of it with the receiver.

“What's going

on

down there?” my mom wants to know. She's up in Gus's room getting him up from his nap.

I wait another day before calling again. “Don't hang up, fuckhead,” I say when he says hello. I don't hear anything after that. “Hello?” I go.

“I'm still here,” he says.

“We got a problem,” I tell him.

“So I hear,” he goes.

“You already know?” I ask.

“You just told me,” he goes.

I'm quiet, thinking about hanging up myself.

“So what's the problem?” he asks.

I imagine pulling the phone off the wall and beating it flat with the mallet my dad keeps in the basement. Living by myself for the rest of my life, and having no friends. “Our pal Hermie says he's getting a gun to go after that kid he hates,” I go.