Qatar: Small State, Big Politics (26 page)

Read Qatar: Small State, Big Politics Online

Authors: Mehran Kamrava

The state’s developmental capacity depends largely on the denseness of state-society relations. The state’s own internal corporate and policy coherence enhances the cohesiveness of societal networks. It also empowers those social groups that share its vision, and also solidifies institutional, normative, and financial ties with them.

48

Given the international nature of Qatar’s development projects, and its manifold and in-depth financial and economic global engagements, globalization plays an important role in the capacity and strength of the Qatari state. In fact, developmental states’ capacities and their embedded autonomy in society tend to benefit from globalization. Engagement and collaboration with global forces enables states to draw on one another’s strengths and to augment their conventional powers.

49

At the same time, as states become more involved in their transformative roles domestically, they often tend to look internationally for a division of labor, and therefore the connections between internal accomplishments and the external context become stronger and more robust.

50

The Qatari state’s embrace of globalization, and especially its assertive presence on the global financial and diplomatic arenas, only adds to its domestic strengths and to the density of its ties with actors in Qatari society.

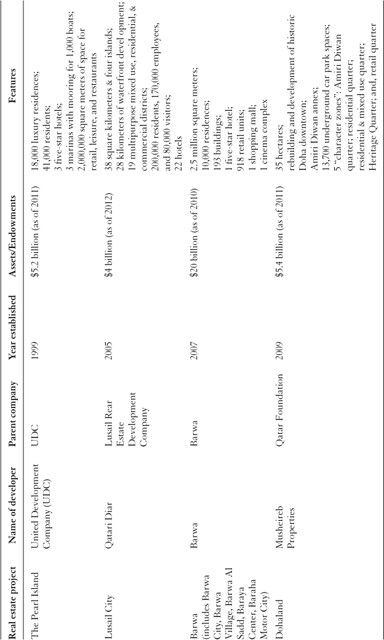

TABLE 5.5.

Real estate development enterprises in Qatar

The Qatari state’s social allies have been pivotal in advancing its various developmental agendas. David Waldner has argued convincingly that the timing of the state’s incorporation of social allies is key to its success in furthering developmental goals. When state formation occurs simultaneously with the political incorporation of the popular classes, economic outcomes tend to reflect the elite’s political concessions rather than their own preferences. But when state-building precedes the incorporation of popular classes, the state has a comparatively freer hand to pursue its desired economic goals and agendas. These two paths of state development can result in the emergence of what Waldner calls “mediated” and “unmediated” states, with the former being those in which “state elites rule through an alliance with local notables,” whereas the latter are those “in which institutions replace notables to link state, economy, and society.”

51

Transformation from mediated to unmediated state requires the establishment of institutions that supplant local notables. Most transitions from mediated to unmediated states occurred at a time when new institutions were not established sufficiently firmly to effectively supplant elites. Thus power-holders sought to enhance their powers by incorporating the masses into the orbit of the state.

52

In Qatar, new institutions have been created, but old ones continue to be kept alongside new ones. The state remains in a hybrid stage, in-between a mediated to an unmediated state. But the older institutions—the Ministry of Education, for example, remain relatively insignificant in the state’s new overall trajectory. They are mere offices for salary-drawing, patronage-dependent, older and relatively marginalized Al Thanis, where they can hang their hats until retirement. Actual power and influence lies elsewhere, in key ministries staffed by the emir’s allies, and in parastatals whose technocratic management shares the emir’s vision of modernity, and who are only too grateful to get rich, or richer, in the process. According to Waldner, “levels of elite conflict determine whether state formation occurs simultaneously with or before popular incorporation.”

53

In Qatar, the consolidation of power within Hamad’s immediate inner circle was secured first—in the mid- to the late-1990s—and then, beginning in the 2000s, the state started expanding its incorporation of social actors, including non-Al Thanis, through fostering rapid and globally oriented economic growth and expansion. Qatar may be in an in-between stage in its transition from a mediated to an unmediated state, but the particular nature of its hybridity appears to have done little to undermine its developmental capacities.

Qatari High Modernism

In addition to its pursuit of subtle power in the international arena, the Qatari state has employed its enormous capacity to bring about what James C. Scott has called a high modernist society. Scott has defined high modernism as

a strong (one might even say muscle-bound) version of the beliefs in scientific and technical progress that were associated with industrialization in Western Europe and in North America from roughly 1830 until World War I. At its center was a supreme self-confidence about continued linear progress, the development of scientific and technical knowledge, the expansion of production, the rational design for social order, the growing satisfaction of human needs, and, not least, an increasing control over nature (including human nature) commensurate with scientific understanding of natural law.

High

modernism is thus a particularly sweeping vision of how the benefits of technical and scientific progress might be applied—usually through the state—in every field of human activity.

54

The core assumption of high modernism is the creation of a new society, by force if need be. In achieving its goal, the state sets out to “conceive of an artificial, engineered society designed, not by custom and historical accident, but according to conscious, rational, scientific criteria.” It undertakes social engineering with zeal and determination, with the hope that “every nook and cranny of the social order might be improved upon.”

55

The project of high modernism is often carried out by authoritarian states that need to rely on coercive practices to accomplish their self-ascribed missions of pulling their societies out of the dark ages and into a new era. Often times, high modernism is premised on a radical break with the past. Insofar as the state is concerned, “the past is an impediment, a history that must be transcended; the present is the platform for launching plans for a better future.” This better future is often most dramatically manifested through spatial and geographic forms that are meant to make life, and governance, easier. Ordinary people, the assumption goes, do not have the necessary intelligence, skills, and experience to fully grasp the superior logic that underlies the high modernist project. But they will buy into it once they see its impressive results at work. As Scott puts it, a key characteristic of the discourse of high modernism is heavy emphasis on “visual images of heroic progress toward a totally transformed future.” High modernism is meant to make a visual statement. “The new city has striking sculptural properties; it is designed to make a powerful visual impact as a

form

.”

56

As an ultra-modern city, however, the high modernist city can be anywhere; it lacks context and individuality.

Qatari high modernism differs from Scott’s ideal type in three important respects. First, although the Qatari state is autocratic, it is of a milder, more benign sort that, so far at least, has not had to rely on force to carry out its modernization projects. In fact, the state has managed to expand and to solidify its base of support through—and at the same time as—fostering high modernism. Critically, instead of being implemented solely by the state, Qatar’s high modernism project is being mostly carried out by state-owned corporations, which incidentally serve as venues for deepening state-society’s linkages through mutually empowering, and financially enriching, ties. Far from being corrosive in the long term of the state’s underpinning authoritarianism, the manner in which Qatari high modernism is unfolding appears to be strengthening the political status quo and adding new dimensions to its already robust clientelistic networks across Qatari society.

A second important difference between Qatari high modernism and the type of high modernism that Scott describes, drawing mostly from South American and former communist East European examples, is the role of tradition. Due largely to its youth and the historical and geopolitical conditions in which its formation occurred, heritage and national identity—the myth of historical resonance and continuity—are central to the traditional legitimacy on which the Qatari state rests. Moreover, by virtue of the nature of the very position he occupies, the emir can ill afford to ignore Qatari tradition and not to continuously pay lip service to it even if the projects he patronizes undermine it. In reality, what has ended up happening is the state carefully walking on a tightrope, fostering high modernism, on the one hand, and a vibrant if contrived heritage industry, on the other.

57

As the new cities and islands being built are concerned, their connections with Qatari culture—even if only in name—are emphasized by the state and by private developers. In one of the promotional materials for Lusail, a city being built north of Doha, the emphasis on mixing Qatari traditions and futuristic aspirations is prominent:

Lusail goes beyond the usual concept of a modern city; it is, in fact, a futuristic reflection of wonderful aspirations, technologies and ideas. Simultaneously, Lusail is characterised by a rich history that captures the authentic heritage and values of the remarkable Qatari culture. The unique name “Lusail” is not only derived from the rare flower that grows in Qatar, it is also a symbol of the authenticity of the place where the late Sheikh Jassem Ben Mohammad Al Thani built the Lusail Castle, previously the centre for governance. In the vicinity of this significant castle lies Lusail, a modernistic city, yet one that has innovatively preserved the traditional aspects of Qatar.

58

Qatari Diar, Lusail City’s developer, further elaborates on its guiding philosophy:

We have a strong desire to ensure the cultural fabric of society is woven into every one of our developments across the world…. Guided by the progressive and forward-looking vision of His Highness the Emir Sheikh Hamad Bin Khalifa Al-Thani and His Highness the Heir Apparent Sheikh Tamim Bin Hamad Al-Thani, Qatar has developed the Qatar National Vision 2030, which provides for the long-term benefit of its people and future generations by creating an advanced society capable of sustaining its development and providing a high standard of living for all.

Since its launch in 2005, Qatari Diar has been dedicated to bringing these ambitious goals to life. More than just a real estate investor and developer, Qatari Diar is the organization proudly entrusted with realizing our country’s vision for a beautifully built environment, new sustainable communities and developments that catch the imagination of a world audience.

59

This, in fact, is where Qatari high modernism most closely approximates Scott’s ideal type. The most visible manifestation of high modernism is the construction of entire cities anew, with Brasilia as a prime example, and the Qatari state has been busily encouraging the proliferation of newly built, modern cities across the country’s sandy cost. The four biggest of such projects are the Pearl artificial island, Barwa, Lusail City, and Dohaland, which, combined, are changing the face and the very urban geography of Qatar, all at a cost of tens of billions of dollars and in the process generating profits in the billions as well.

Table 5.5

offers a snapshot of the scope and magnitude of these projects. Considering that greater Doha has an approximate size of only 50 square miles, once on line, these projects will substantially change the spatial life and geographic look of the entire country. The Pearl is an artificial island being built north of Doha and, when completed, is meant to comprise two separate islands each with their own string of smaller islands. Lusail is being modeled as a futuristic, environment-friendly city. Barwa comprises several mega-projects to provide everything from luxury to low-cost housing and a motor speedway. And Dohaland is an urban planning project undertaken by the Qatar Foundation designed to rebuild large swathes of downtown Doha in the form of modern, multipurpose areas. The government has also announced plans for planting a billion trees across the country. Where there is sand today, there will soon be glass, concrete, and greenery.

All of this is meant to transform Qatar into a showcase example of an ultra-modern, advanced country. Barwa’s mission statement is emblematic of what all these projects represent and what they hope to accomplish: “Barwa’s creation was a demonstration of the vision of the country led by His Highness the Emir and the government of the State of Qatar to build a modern country with a diversified economy for the benefit of future generations. We seek to contribute to the government’s over-arching development plan for the State set out in

Qatar Vision 2030

.”

60