Qatar: Small State, Big Politics (6 page)

Read Qatar: Small State, Big Politics Online

Authors: Mehran Kamrava

Today, the GCC’s eastward look has resulted in the expansion of trade and economic ties between the two regions along manifold lines, except for defense and security, which remains an American preserve. India has signed defense cooperation agreements with Qatar and Oman, but the agreements are superficial at best and cover areas such as maritime security, the sharing of data, and common threat perceptions.

87

It is, instead, in trade and investments, flowing in both directions, in which the real interface between the GCC and Pacific Asia lies. Almost all of Qatar’s oil sales go to China, for example, and China has signaled its commitment to long-term energy trade with Qatar.

88

Despite concerted efforts at diversification, China’s gas imports are likely to grow in the future, principally from the Persian Gulf.

89

Japan and South Korea are both also heavily dependent on gas and oil imports from the Persian Gulf, with Japan importing fully 96 percent of its gas from the region and South Korea 93 percent.

90

Equally important is the role of migrant labor, with approximately 70 percent of the GCC’s labor force coming from Asia, and sending home some $40 billion in remittances annually.

91

A New Center of Gravity

By all accounts, the GCC has emerged as a global economic powerhouse. In fact, along with the other so-called mega-emergers, comprised of the BRIC countries (Brazil, Russia, India, and China) and Mexico, the economies of the Arabian Peninsula are expected to grow until 2020–2030, before convergence with OECD levels of per capita gross domestic product is expected to dampen their growth potential.

92

GCC policymakers have developed a consensus on three themes, namely asset market liberalization, privatization through initial public offerings, and increased investment in infrastructure, each of which have enhanced the attractiveness of the region as a source for increased foreign direct investment.

93

Both individually and in combination with one another, these developments have turned the GCC into an important economic force.

94

This economic rise has been facilitated through a confluence of three primary developments. First, there continues to be sustained high global energy demands, whose prices have been consistently high due to market speculation and chronic tensions in the Persian Gulf region, most notably between the United States and Iran. Global energy demands, which have been growing at 1.85 percent over the past decade, are expected to grow at a robust annual rate of 2.9 percent to 2020, before gradually retreating to 2.1 percent per annum through the 2030s and to stabilize around 1 percent per annum thereafter.

95

Energy demands on the parts of the BRICs, with whom the GCC maintains close and expanding commercial relations, are projected to grow around 5.3 percent annually into the mid-2010s before declining to 2 percent in the 2020s and 1.3 percent thereafter.

96

The Persian Gulf remains central to the global energy industry. In 2010, the Persian Gulf states, including Iraq, were estimated to hold more than 54 percent of the world’s oil reserves and more than 40 percent of its natural gas.

97

In the coming decades, the GCC is expected to continue to capitalize on its energy resources to supply the bulk of global demand. It is estimated that between 2005 and 2030, approximately 38 percent of the projected increase in the global oil supply will come from the GCC, whose production will grow by 72 percent.

98

In specific relation to Qatar, the sheikhdom is expected to lead the GCC’s natural gas production in the coming decades, which is expected to grow by 200 percent between 2005 and 2030.

99

This will not be inexpensive. The International Energy Agency estimates that the total capital expenditure needed by the GCC states to sustain a steady 2.2 percent increase in crude oil production and a 5.6 percent increase in natural gas production will be approximately $650 billion over the next twenty-five years (at 2006 prices).

100

If current dynamics and trends continue, there is no reason to believe that the GCC states will not be able to come up with the needed resources, either on their own or through FDI flows, to continue investing in their oil industries.

A second development facilitating the GCC’s economic rise has been the increasing ability of local actors to make the best use of oil windfall revenues.

101

This has been facilitated by the development of absorptive financial and infrastructural capacity on the part of the GCC states, which has enabled them to retain much of the windfalls from the second oil boom (2002–2008) within the region instead of recycling it through Western financial institutions as they did in the 1970s.

102

The establishment of a number of additional investment vehicles, the most notable of which are sovereign wealth funds and government investment corporations, in addition of course to Central Banks, is a case in point.

103

Between 2001 and 2006, GCC-based bank assets doubled to $500 billion.

104

Although GCC sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) took heavy hits during the 2008 financial crisis, they were used effectively to shore up and stabilize domestic economies.

105

Martin Hvidt maintains that even at a modest 5 percent interest earning on current investments, GCC states will earn an additional $77 billion on annual income.

106

The combined global wealth managed by the SWFs is expected to grow at 15 percent per annum until 2015, reaching $10 trillion. For many countries, especially those in the Arabian Peninsula, this means that they will become increasingly asset-based rather than commodity-based economies as their revenues from foreign assets will exceed their commodity revenues.

107

There are also massive sums of private revenues that are being invested by the so-called high net worth individuals.

108

According to one estimate, private individuals who actively invest in global financial markets hold at least 40 percent of the foreign wealth purchased with petrodollars.

109

The ensuing financial influence has brought the GCC states active membership and influence in international financial organizations such as the World Trade Organization. Along with the BRICs, in fact, Saudi Arabia has sought to reshape the architecture of international financial institutions.

110

The GCC states have also begun taking “proactive steps in reshaping the institutional design of global frameworks of governance.”

111

According to one observer, membership in such international forums enables the GCC to “benchmark domestic governance to international standards, while participation in an international rules-based system introduces a new dynamic to domestic reform processes. It also enhances regional familiarity with global values and helps to embed them in local discourses while situating Gulf states’ views of global governance within a broader non-Western paradigm shared by many developing countries, including India and China.”

112

This is one of those areas where the rubber of globalization hits the road, and in so doing, makes the GCC states beneficiaries of their expansive engagement with the global economy.

Further enhancing the GCC’s nexus with the global economy has been the establishment of world-class airlines that are playing critical roles in facilitated linkages between industrial and financial hubs in the East and the West. Etihad, Emirates, and Qatar Airways have all emerged as “super-connectors” capable of connecting any two parts of the world with one stopover in the Persian Gulf, therefore bringing about a “fundamental reshaping of the map of global aviation power.”

113

As high-profile national symbols, these airlines also serve important branding purposes, flying thousands of passengers from one destination to another through GCC-based national flag carriers. By 2015, Emirates is expected to become the world’s largest operator of wide-body jets.

114

Related to this has been a third development, namely savvy investment decisions on the part of the GCC, resulting in flows of ever-increasing amounts of FDI into the region from both the East and the West. FDI flowing into the GCC shot up from $392 million in 2000 to approximately $63 billion in 2008, an increase of 160 times.

115

Although following the 2008 global financial crisis the flow of FDI into the larger Middle East declined significantly, FDI flow into the UAE (Abu Dhabi and Dubai), Saudi Arabia, and Qatar have continued to grow after 2009.

116

These investments reflect decisions meant to minimize the effects of sharp oil price movements and other exogenous shocks, such as an eruption of hostilities involving Iran, to which the region remains vulnerable.

117

Two features of the current GCC investments are particularly note-worthy. First, insofar as their domestic investments are concerned, in addition to enhancing infrastructure and attracting further FDIs, revenues from the second oil boom are being used to invest substantial sums in human development, most notably tertiary education, health care, and the fostering of knowledge-based economies in preparation for the post-oil period.

118

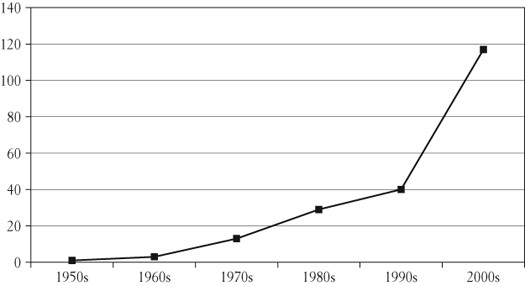

Perhaps the most dramatic example of this type of investment has been in the establishment of new universities, or the attraction of branch campuses, which resulted in the growth of universities in the GCC from 1 in the 1950s (in Saudi Arabia) to 13 in the 1970s, 29 in the 1980s, 40 in the 1990s, and 117 in the 2000s, an increase of over 290 percent in a decade (Figure 2.1). Similarly significant investments have been made at the primary and secondary school levels, as well as in public health, skills enhancement and job creation schemes, and other areas of human development.

Figure 1.1.

Number of universities in the Gulf Cooperation Council states

Note:

Data collected by author.

Second, in addition to investing domestically, GCC states have decided to invest regionally, within the Middle East, specifically in North Africa and the Levant. These investment decisions, which have helped perpetuate the uneven relationship between the GCC and other parts of the Arab world, are driven by several factors. These investments are seen as one way to help ensure economic stability in a region from which many Gulf-based migrant laborers come.

119

Equally helpful have been major economic reform programs launched in the Mashreq beginning in the mid-1990s, such as the one initiated in Egypt in July 2004, meant to offer regional investors attractive investment environments. There have been other indirect benefits, such as increased remittances from GCC-based laborers back to their home countries, and expanding exports and tourism revenues, especially before the 2011 uprisings.

120

To help stem the tide of the Arab Spring from engulfing other regional monarchies, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, the UAE, and Qatar each pledged $1.25 billion worth of developmental assistance to Jordan, though by late 2012 none of the aid had yet materialized.

121

Most countries of the Middle East are clamoring for Persian Gulf investments, having made the attraction of private sovereign capital from those they once frowned on as one of the cornerstones of their national development strategies, with the small sheikhdoms “dominating development throughout the region.”

122

For example, by one account approximately 50 and 75 percent of stocks in the Egyptian and Jordanian stock exchanges, respectively, are owned by Persian Gulf Arabs.

123