Read Qatar: Small State, Big Politics Online

Authors: Mehran Kamrava

Qatar: Small State, Big Politics (8 page)

Purposive leadership and attempts at agenda setting bespeak of the importance of agency. This has to do with a second factor that has facilitated Qatar’s emergence as a tiny giant, namely the institutional autonomy and the policy agendas of the Qatari political leadership. Unlike the Kuwaiti system, whose proactive parliament at times brings the country’s entire policymaking process to the brink of paralysis, or the factional politics of the Saudi royal family, or the besieged and largely unpopular Bahraini royals, Qatar’s leadership is focused, unencumbered by the hassles of parliamentary politics, and, made-up as it is of a handful of individuals, is driven and determined in its pursuit of domestic, regional, and global ambitions. The emir of Qatar has articulated an ambitious vision of the country as a leader in Arab diplomacy, arts and culture, scientific innovation, and development. How realistic or substantive these goals and ambitions are is ultimately less important than the ability to pursue them—whether through purchase and wholesale importation or through mobilizing domestic resources, or both—and the perceptions that come with such pursuits. Justifiably or not, Qatar is generally perceived to be a leader, or to have substantive claims to leadership, in the Arab world. Perceptions often shape and become reality, regardless of whether or not they are accurate.

A third factor facilitating Qatar’s rise to regional prominence, this one structural, has to do with domestic dynamics, namely lack of domestic fissures and fragmentations. Compared to most of its regional cohorts, Qatar enjoys remarkable social cohesion. Given their over-reliance on hydrocarbon exports, most GCC states have been quite vulnerable to cycles of boom and bust.

149

The one thing certain about oil is the uncertainty of its prices.

150

States with a fragile resource base in particular—most notably Bahrain, Yemen, and Saudi Arabia—can face serious challenges in times of economic downturns. The existence of numerous “fault-lines” and “fissures,” along sectarian lines for example, can “heighten regime vulnerability to future politicization and contestation if resource scarcities develop and persist.”

151

This is not the case in Qatar, where the sectarian tensions of Bahrain between the Sunni and the Shia, the confederation divisions of the UAE, and the sectarian and geographic disparities marking Saudi society are all conspicuously absent. Qatar’s estimated 10 to 20 percent Shia minority is comparatively well integrated into the economic mainstream and even, to the extent possible, into the political establishment. Within the Arabian Peninsula, Qatar stands out uniquely for its absence of social frictions arising from societal divisions.

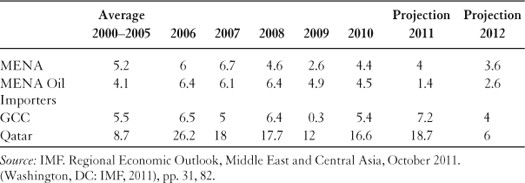

A fourth and final factor that ties the other three together and underlies the whole Qatari phenomenon is the abundance of financial resources at the disposal of the state. Qatar is an inordinately wealthy country, with a very small population. As

table 1.1

indicates, Qatar has the highest growth rate in its real gross domestic product compared to any other country in the GCC or the larger Middle East. This has enabled the ruling elites to ensure socio-economic security for their citizenry, and mitigated potential political dissatisfaction.

Much of this wealth comes from Qatar having strategically positioned itself as the world’s largest supplier of liquefied natural gas (LNG).

152

As it happens, Qatar and Iran share the world’s largest gas field, covering an area of 9,700 square kilometers, of which 3,700 square kilometers is in Iranian territorial waters (called South Pars by the Iranians) and 6,000 square kilometers is in Qatari territorial waters (called the North Field or North Dome by the Qataris). Hampered by protracted delays and international sanctions, Iran has hardly been able to capitalize on its gas resources, extracting only 35,000 billion barrels per day from the gas field as compared to Qatar’s 450,000 barrels per day.

153

Although Qatar first began LNG production from the North Field in 1991 and started its LNG exports only in 1997, by 2006 it had become the world’s largest LNG exporter. Aided by massive investments by international oil companies, most notably ExxonMobil and Shell, and also by the state-owned Qatar Petroleum, the country’s LNG production went from 23.7 billion cubic meters (bcm) in 2000 to 116.7 bcm in 2010.

154

The resulting financial windfalls, especially for such a small country, have been nothing short of phenomenal.

TABLE 1.1.

Real GDP growth in MENA, GCC, and Qatar (annual change and percentage)

Chapter 5 discusses Qatar’s pursuit of what James C. Scott calls “high modernism” and, in Qatar’s case, the creation of a new country and a new society almost from scratch.

155

The bulk of the next two chapters are devoted to examining the means through which Qatar uses its wealth to further its geostrategic interests. Here I mention only a couple of examples to illustrate how Qatari resources are used to enhanced the country’s regional position in relation to its immediate neighbors: the Dolphin project, through which LNG is supplied to the UAE and Oman, is meant to “strengthen political ties” and to enhance Qatar’s position within the GCC as a supplier of energy to other energy-rich countries. Gas sales to the West and to Pacific Asia are used for similar purposes. Finally, talks of opening up the local economy to Bahraini labor will add a dimension of economic dependence to Bahrain’s relationship with Qatar.

156

Qatar’s wealth, and its strategic use of that wealth, have everything to do with what the country has turned into today.

Given this chapter’s focus on the international relations of the Persian Gulf, it seems befitting to end it with a note on Qatar’s regional role. A central question here has been whether Qatar, through its foreign policy pursuits and resulting international conduct, is influencing, at least on the margins, or perhaps even giving shape to an emerging international regime in which it plays a highly consequential, even central, role. International regimes “authorize certain types of bargaining for certain purposes” and “facilitate negotiations leading to mutually beneficial agreements among governments.”

157

As “rational egotists,” states monitor each other’s behavior, develop self-enforcing norms and principles, slowly adjust their own behavior accordingly, and give rise to “rule of thumb” for international behavior.

158

Whether or not Qatar is actively trying to carve out an international regime—or is even in a position to do so—is far from clear.

159

What is obvious is that within the larger US-dominated international regime over much of the Persian Gulf and the Middle East, Qatar is making changes around the margins, pursuing its own interests whenever and as much as possible regardless of who else’s interests they might be in variance to, and in the process is making a huge splash internationally and ruffling feathers both far and near.

2

T

HE

S

UBTLE

P

OWERS OF A

S

MALL

S

TATE

Conceptions of international relations have traditionally revolved around the importance of the great powers. The story of international relations has been one of great powers and of their rivalries and power machinations.

1

Scholars of international politics have long seen power as the preserve of the big. Size, when it comes to the conduct of interstate relations, matters. Kenneth Waltz has been one of the most notable proponents of this line of thinking. “The theory, like the story, of international politics,” he writes, “is written in terms of the great powers of an era.”

2

Interactions among the major states are far more likely to be consequential for the larger international system than among the minor ones. In fact, he maintains, “a general theory of international politics is necessarily based on the great powers.”

3

As already discussed, at least insofar as the distribution of power in the Middle East and North African subsystem is concerned, there has been a steady shift in the direction of the Persian Gulf in general and the position and powers of Qatar in particular. With the broader regional context thus examined, we now turn our attention to the specific case of Qatar and the dynamics that underlie its regional and global positions of strength and power. This chapter examines the broad parameters of Qatar’s position in the international system, looking specifically at its sources of what may be called “subtle power.”

I begin with a discussion of the typical roles, profile, and position of small states in the international system. For the most part correctly, international relations scholars have situated small states on the receiving end of power rather than as influencers and, much less, as sources of power. Qatar, a small state by any definition, bucks the trend.

I argue that traditional conceptions of power no longer adequately describe emerging trends shaping the international system. Realist and neorealist thinkers have viewed power in terms of access to and control over tangible resources, especially manpower and military strength. More recently, notions of first soft power and then smart power have sought to rectify seemingly narrow and increasingly unfeasible focus of realists on force and military hardware. None of these conceptions adequately describe the underlying dynamics that account for the position that Qatar—an otherwise small state on the margins of global power politics—has been able to carve out for itself. That Qatar has been able to create a distinct niche for itself on the global arena, that it plays on a stage significantly bigger than its stature and size would warrant, that it has emerged as a consequential player not just in the Persian Gulf and the Arabian Peninsula but indeed across the Middle East and beyond, all bespeak of its possession of a certain type and amount of power. By definition, it cannot be hard or soft power, or their combination of smart power. It is a type of power that may be best viewed as “subtle power.”

Small States in World Politics

International relations literature has generally treated small states as peripheral actors in international politics, seeing them often in need of protection from more powerful patrons and forced to adopt various accommodative strategies toward both stronger neighbors and international actors.

4

Thus relegated to the shadows of greater powers, small states are generally assumed to be at best of secondary importance in international power politics and lacking the necessary means and resources that affect the circumstances in which they find themselves.

5

More recently, attention has focused on not just the small states’ vulnerability, which is a structural condition, but also on their resilience, which is a product of agency and strategy.

6

Given the right circumstances, however, small states can actually go beyond simple resilience—that is dealing with adversities and the limitations that size and demography impose on them. In fact, they can become highly influential both regionally and in the larger global arena, to the point of exerting significant amounts of power and influence in their immediate neighborhood and beyond.

This is indeed the case with Qatar, which has emerged as a major player in the Persian Gulf and Middle East subregions, despite a preponderance there of much larger and more powerful actors. In Qatar’s case, several factors have combined to facilitate this emergence as an influential regional and international player. They include a highly calibrated and carefully maintained policy of hedging; an equally aggressive global campaign of branding; significant capacity on the part of the state; and prudent use of the country’s comparative advantage in relation to neighbors near and far.

When it comes to regional and international diplomacy, Qatar’s foreign policy appears to be at best an incongruent reflection of the idiosyncrasies of its chief architects—namely the country’s emir and the prime minister—and at worst inconsistent and maverick. On the surface, Qatar also appears to consistently “punch above its weight.”

7

Especially for a small state located in one of the world’s toughest neighborhoods, Qatar’s foreign policy appears woefully out of step with the size of the country, the preponderance of “great” and “secondary” powers vying for regional influence and position—most notably the United States and Iran—and the conventional power capabilities at its disposal.

8

Nevertheless, on closer examination Qatar’s foreign policy pursuits are actually quite logical, a product of the country’s successful, and in some ways fortuitous, positioning of itself as a small but highly influential actor in fostering regional peace and stability in a neighborhood that is justifiably renowned for its instability.

I posit two central theses here. First, I maintain that small states can indeed become influential players in the international arena, and, although they may be in need of military protection from others, they can use foreign policy strategies such as hedging to greatly strengthen their leverage vis-à-vis potential foes and friends alike. Although constrained by a number of structural weaknesses and vulnerabilities, small states can use their “individual actor-ness” not only to overcome vulnerabilities and demonstrate resilience, but, in fact, to become regionally and internationally important players.

9

Next, my argument points to the need to rethink and refine existing conceptions of power, with traditional assumptions about power as rooted in military strength or cultural values—that is, hard and soft power—no longer adequately describing the emerging nature of Qatar’s position in the Persian Gulf and in the larger Middle East. Qatar’s influence and power are neither military nor cultural—nor a combination of the two, the so-called smart power

10

—but are derived from a carefully combined mixture of diplomacy, marketing, domestic politics, regional diplomacy, and, through strategic use of its sovereign wealth fund, increasing access to and ownership over prized commercial resources. This bespeaks of a new form of power and influence, one that is more subtle in its manifestations and is less blunt and blatant, one that may more aptly be dubbed subtle power.

The discussion begins with a brief examination of the role and position of small states in world politics, and the policy options they tend to adopt in order to adjust to international circumstance and to protect and further their interests in the international arena.

11

Despite serious disadvantages in military and diplomatic power, small states resort to one or more of three options—alliances, norm entrepreneurship, and hedging—in order to enhance their position and leverage in the international arena.

Small states do indeed face a number of both political as well as economic disadvantages in the international arena. Economically, they have to contend with a number of inherent vulnerabilities and deficiencies, such as inadequate or insufficient resources, limited opportunities for diversification, trade dependence, limited institutional capacity in the public and private sectors, comparatively high costs for services and transportation, and exposure to environmental and other exogenous shocks.

12

The political and diplomatic disadvantages that small states face in the international arena tend to be just as restrictive. The position and role of small states in the international arena are often at best reactive, vulnerable to outside events, and naturally contingent on the priorities and postures of the great powers, on whom the small and the weak rely for security and protection.

13

All of this is not to imply that small states are hapless recipients of power and influence by the stronger actors in the international arena. In fact, small states have been able to enhance their leverage and influence both within the community of greater powers and between them using one or more of three options, namely through forging alliances, mustering up issue-specific power, and a delicate balancing act commonly referred to as “hedging.”

One of the more prevalent, as well as effective, ways in which small states compensate for their lack of power and influence in the international arena is through entering formal or informal alliances with more powerful patrons. According to Walt, states join alliances in response to threats and not necessarily out of ideological affinity or because of “bribery” (aid, development assistance, etc.), the latter two tending to strengthen existing alliances rather than creating them.

14

For small states, alliances with a greater power may be informal or may take the form of signing of a formal treaty of protection from outside threats.

15

Besides providing protection, alliances serve as enabling mechanisms for small states in a number of important ways.

Small states that bandwagon or enter into formal alliances often do so through a delicate series of bargains that enhance their leverage vis-à-vis the great power protector. These bargains may entail one or more combinations of formal negotiations, bargains with separable elements of the great power, and influencing domestic opinion and private interest groups through lobbying efforts.

16

Moreover, alliances enable small states “not only to enhance their military security but also to obtain a variety of non-military benefits, such as increased trade or support for domestic political regimes.”

17

Equally important are the benefits of membership in multistate alliances and institutions, the most notable being the European Union (and the European Commission in particular) and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, whose decision- and policymaking structures tend to be biased in favor of small states and in which small states tend to be overrepresented.

18

In the United Nations, small states often “intervene to provide a basis for compromise on divisive issues.”

19

Alliances, of course, do not come without costs, inhering potentially glaring contradictions between influence, on the one hand, and autonomy, on the other.

20

Small states especially risk losing policy autonomy or flexibility in the face of international crises involving the more powerful patron.

21

“In their more benign forms,” according to one observer, the trade-offs between sovereignty and protection are “negotiated and transparent.”

22

They can, however, take the form of “less opaque infringements on sovereignty.” There are also the risks of “entrapment” and “abandonment” for small states that enter into alliance with a larger power, with the former arising when a strong dependence on the alliance locks the small state’s policy options to those of the stronger ally even if they are harmful to the small state’s interests, and the latter becoming a possibility when alliance ties are too loose and the pluses of breaking them outweigh the costs of maintaining them.

23

Apart from using alliance politics and other systemic factors to their advantage—for example the structure of the international system (hierarchical, hegemonic, or balance of power), or the state of the international system (in terms of degree of tension)—small powers may also resort to international norms, as well as their own agency and actions, in order to enhance their influence in international politics.

24

In particular, through persistent activism in and unrelenting attention to specific issues, some small states have been able to emerge as important norm entrepreneurs on the international stage. According to Kingdon, when it comes to agenda-setting, a policy entrepreneur is more likely to be taken seriously if recognized as an expert on the policy issue in question.

25

Unsurprisingly, a number of small (European) states have developed reputations as “forerunners” and “role models” on certain norms and issues, thus exerting disproportionate influence in the relevant policy areas: Sweden on environmental issues; Sweden, Denmark, and the Netherlands on issues related to gender; and Belgium and the Netherlands on monetary and economic union.

26

Needless to say, for small states aspiring to become policy entrepreneurs, the likelihood of success is enhanced if they are seen as impartial and honest brokers interested in the greater good.

27

Having sufficient financial and human resources to support a particular initiative can only be a plus. Undoubtedly, there are a number of states that are small and weak. There are also states that are small and influential, of which Israel, the Nordic countries, and Singapore are prime examples.

28

Qatar belongs in the latter category.