Quirkology (24 page)

Authors: Richard Wiseman

The second part of the study presented participants with the task described at the beginning of this section. Take another look at the two images shown in

figure 7

. There is only one very small difference between the images—the pupils in the image on the right have been digitally enhanced and so are larger than the pupils in the image on the left. People’s pupils tend to become larger when they see something, or somebody, that appeals to them. Moreover, because we tend to like people who like us, people with enlarged pupils are often seen as especially attractive. The signal is subtle, but the effect is powerful. It has also been known about for a long while. During the seventeenth century, Venetian women would place an extract of the plant belladonna, which contains a toxin that dilates the pupil, into their eyes to appear more attractive. This unusual practice explains the origin of the plant’s name:

bella donna

means “beautiful lady” in Italian. The toxin would also have had the side effect of making the Venetian women’s vision somewhat blurry, perhaps also giving rise to the expression “Love is blind.”

figure 7

. There is only one very small difference between the images—the pupils in the image on the right have been digitally enhanced and so are larger than the pupils in the image on the left. People’s pupils tend to become larger when they see something, or somebody, that appeals to them. Moreover, because we tend to like people who like us, people with enlarged pupils are often seen as especially attractive. The signal is subtle, but the effect is powerful. It has also been known about for a long while. During the seventeenth century, Venetian women would place an extract of the plant belladonna, which contains a toxin that dilates the pupil, into their eyes to appear more attractive. This unusual practice explains the origin of the plant’s name:

bella donna

means “beautiful lady” in Italian. The toxin would also have had the side effect of making the Venetian women’s vision somewhat blurry, perhaps also giving rise to the expression “Love is blind.”

What has all of this to do with love at first sight? My theory was that people who experienced this phenomenon may, without realizing it, be especially sensitive to nonverbal signals of attraction. If this was correct, then in the experiment such people would be especially likely to be drawn to the images containing enlarged pupils. During the experiment, people were shown several pairs of photographs and were asked to indicate which image in each pair they found most attractive. The data was fascinating. First, women were far more sensitive to pupil size than men. Time and again they would choose the image with the larger pupils, but the men tended to check the “uncertain” box. Second, when I focused on those people who had experienced love at first sight, this effect was much more striking. Women who had experienced love at first sight were super-sensitive to signals of attraction, whereas men who had experienced this strange phenomenon were relatively insensitive to the same cues. This provides tentative evidence that the love-at-first-sight experience, at least in women, may be driven by an enhanced ability to detect subtle signals of attraction.

The study revealed that love at first sight is surprisingly frequent, often leads to long-lasting relationships, and might be driven (at least in women) by a sensitivity to certain types of subtle nonverbal cues. In short, that there is far more to this curious phenomenon than first meets the eye.

5

THE SCIENTIFIC SEARCH FOR THE WORLD’S FUNNIEST JOKE

Explorations into the Psychology of Humor

I

n the 1970s, the cult comedy show

Monty Python’s Flying Circus

created a sketch based entirely around the idea of finding the world’s funniest joke. In the 1940s, a man named Ernest Scribbler thinks of the joke, writes it down, and promptly dies laughing. The joke turns out to be so funny that it kills anyone who reads it. Eventually, the British military realize that it could be used as a lethal weapon, and so they arrange to have a team of people translate the joke into German. Each person translates just one word at a time in order not to be affected by the joke. The joke is then read out to German forces, and it is so funny that they are unable to fight because they are laughing so much. The sketch ends with footage from a special session of the Geneva Convention in which delegates vote to ban the use of joke warfare.

n the 1970s, the cult comedy show

Monty Python’s Flying Circus

created a sketch based entirely around the idea of finding the world’s funniest joke. In the 1940s, a man named Ernest Scribbler thinks of the joke, writes it down, and promptly dies laughing. The joke turns out to be so funny that it kills anyone who reads it. Eventually, the British military realize that it could be used as a lethal weapon, and so they arrange to have a team of people translate the joke into German. Each person translates just one word at a time in order not to be affected by the joke. The joke is then read out to German forces, and it is so funny that they are unable to fight because they are laughing so much. The sketch ends with footage from a special session of the Geneva Convention in which delegates vote to ban the use of joke warfare.

In a strange example of life imitating art, in 2001 I headed a team carrying out a year-long, scientific search for the world’s funniest joke. Instead of exploring the potential military applications of jokes, we wanted to take a scientific look at laughter.

In addition to finding the joke that had maximum mass appeal, my Pythonesque project resulted in a string of surreal experiences involving the internationally syndicated humorist Dave Barry, a giant chicken suit, the Hollywood actor Robin Williams, and more than five hundred jokes ending with the punch line “There’s a weasel chomping on my privates.”

More important, the project also provided considerable insights into many of the questions facing modern-day humor researchers. Do men and women laugh at different types of jokes? Do people from different countries find the same things funny? Does our sense of humor change over time? And if you are going to tell a joke involving an animal, are you better off making the main protagonist a duck, a horse, a cow, or a weasel?

In June 2001, I was contacted by the same august scientific body that had commissioned my study into financial astrology, the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BAAS). The BAAS were eager to create a project that would act as a center-piece for a year-long national celebration of science, and they wanted a large-scale experiment that would attract public attention. Would I be interested in creating it and, if so, what would I choose to investigate?

After a few “close, but no cigar” moments, I happened to see a rerun of the

Monty Python

sketch involving Ernest Scribbler, and I

Monty Python

sketch involving Ernest Scribbler, and I

started to think about the possibility of

really

searching for the world’s funniest joke. I knew that there would be a firm scientific underpinning for the project because some of the world’s greatest thinkers, including Sigmund Freud, Plato, and Aristotle, had written extensively about humor. In fact, the Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein was so taken with the topic that he once stated that a serious work in philosophy could be written entirely of jokes. I then discovered that whenever I mentioned my idea to people, it provoked a serious discussion. Some queried whether there really was such a thing as the world’s funniest joke. Others thought that it was impossible to analyze humor scientifically. Almost everyone was kind enough to share a favorite joke with me. The rare mix of good science and popular appeal meant that the idea felt right.

really

searching for the world’s funniest joke. I knew that there would be a firm scientific underpinning for the project because some of the world’s greatest thinkers, including Sigmund Freud, Plato, and Aristotle, had written extensively about humor. In fact, the Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein was so taken with the topic that he once stated that a serious work in philosophy could be written entirely of jokes. I then discovered that whenever I mentioned my idea to people, it provoked a serious discussion. Some queried whether there really was such a thing as the world’s funniest joke. Others thought that it was impossible to analyze humor scientifically. Almost everyone was kind enough to share a favorite joke with me. The rare mix of good science and popular appeal meant that the idea felt right.

I presented the BAAS with my plans for an international, Internet-based project called LaughLab. I would set up a Web site that had two sections. In one part, people could input their favorite jokes and submit them to an archive. In the second section, participants could answer a few simple questions about themselves (such as sex, age, and nationality), and then rate how funny they found various jokes randomly selected from the archive. During the year, we would slowly build a huge collection of jokes and ratings from around the globe; from this we would be able to discover scientifically what makes different groups of people laugh and which joke made the whole world smile. Everyone at the BAAS nodded, and LaughLab got the green light.

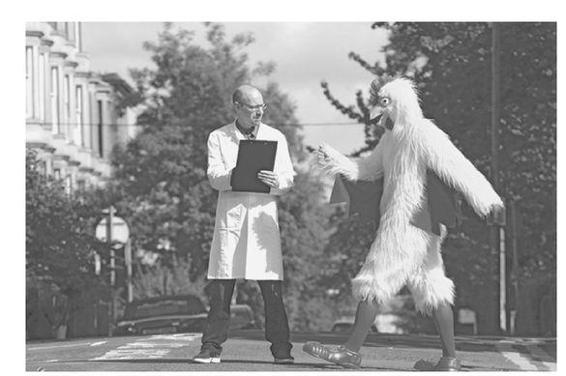

The success of the project hinged on being able to persuade thousands of people worldwide to come online and participate. To help spread the word, the BAAS and I launched LaughLab by staging an eye-catching photograph based around perhaps the most famous (and, as we would go on to prove scientifically, least funny) joke in the world: “Why did the chicken cross the road? To get to the other side.” Toward the end of 2001, I found myself standing in the middle of a road dressed in a white laboratory coat and holding a clipboard (see

fig. 8

). Next to me was a student dressed in a giant chicken suit. Several national newspaper photographers were lined up in front of us, snapping away, and I can still vividly remember one of them looking up and shouting: “Can the guy playing the scientist move to the left?” I shouted back “I

am

a scientist,” and then looked sheepishly at the giant chicken standing next to me. It was the type of surreal experience that was to occur all too frequently throughout the next twelve months.

fig. 8

). Next to me was a student dressed in a giant chicken suit. Several national newspaper photographers were lined up in front of us, snapping away, and I can still vividly remember one of them looking up and shouting: “Can the guy playing the scientist move to the left?” I shouted back “I

am

a scientist,” and then looked sheepishly at the giant chicken standing next to me. It was the type of surreal experience that was to occur all too frequently throughout the next twelve months.

The launch was successful, and LaughLab made its way into newspapers and magazines all over the world. Within a few hours of opening the Web site for business, we received more than five hundred jokes and 10,000 ratings. Then we hit a major problem: Many of the jokes were a tad crude. Actually, I am understating the issue. They were absolutely filthy. One especially memorable submission involved two nuns, a large bunch of bananas, an elephant, and Yoko Ono. We couldn’t allow these submissions into the archive because we had no control over who would visit the site to rate the jokes. With a backlog of more than three hundred jokes from the first day alone, we needed someone to work full time to vet them. My research assistant, Emma Greening, came to the rescue. Every day for the next few months, Emma carefully looked at every joke and excluded those that were not suitable for family viewing. She was often frustrated by seeing the same jokes again and again (the joke “What is brown and sticky?” “A stick” was submitted more than three hundred times); but on the upside, Emma now owns one of the largest collections of dirty jokes in the world.

Fig. 8

A giant chicken crosses the road to help promote LaughLab.

A giant chicken crosses the road to help promote LaughLab.

Participants were asked to rate each joke on a 5-point scale ranging from “not very funny” to “very funny.” To simplify our analyses, we combined the 4 and 5 ratings to make a general “yes, that is quite a funny joke” category. We could then order the jokes on the basis of the percentage of responses that fell into this category. If the joke really wasn’t very good, then it might have only 1 or 2 percent of people assigning it a rating of 4 or 5. In contrast, the real rib-ticklers would have a much higher percentage of top ratings. At the end of the first week, we reviewed some of the leading submissions. Most of the material was pretty poor and so tended to obtain low percentages. Even the top jokes fell well short of the 50 percent mark. Around 25 to 35 percent of participants found the following jokes funny, and so they came toward the top of the list:

A teacher decided to take her bad mood out on her class of children and so said, “Can everyone who thinks they’re stupid, stand up!” After a few seconds, just one child slowly stood up. The teacher turned to the child and said, “Do you think you’re stupid?”“No,” replied the child, “but I hate to see you standing there all by yourself.”Did you hear about the man who was proud when he completed a jigsaw within thirty minutes, because it said “5-6 years” on the box?Texan: “Where are you from?”Harvard graduate: “I come from a place where we do not end our sentences with prepositions.”Texan: “Okay—where are you from, Jackass?”An idiot was walking alongside a river when she spied another idiot on the other side of the river. The first idiot yelled to the second idiot: “How do I get to the other side?” The second idiot responded immediately: “You’re already

on

the other side!”

The top jokes have one thing in common—they create a sense of superiority in the reader. The feeling arises because the person in the joke appears stupid (the man with the jigsaw), misunderstands an obvious situation (the idiots on the riverbank), pricks the pomposity of another (the Texan answering the Harvard graduate), or makes someone in a position of power look foolish (the teacher and the child). These findings provided some empirical support for the adage about the difference between comedy and tragedy: “If

you

fall down an open manhole, that’s comedy. But if

I

fall down the same hole . . . ”

you

fall down an open manhole, that’s comedy. But if

I

fall down the same hole . . . ”

The observation that people laugh when they feel superior to others dates back to around 400 BC, and was described by Plato in his famous text

The Republic.

Proponents of this “superiority” theory believe that the origin of laughter lies in the baring of teeth, akin to “the roar of triumph in an ancient jungle duel.” Because of these animalistic and primitive associations, Plato was not a fan of laughter. He thought that it was wrong to laugh at the misfortune of others and that hearty laughter involved a loss of control that made people appear to be less than fully human. In fact, the father of modern-day philosophy was so concerned about the potential moral damage that could be created by laughter that he advised citizens to limit their attendance at comedies and never to appear in this lowest form of the dramatic arts.

The Republic.

Proponents of this “superiority” theory believe that the origin of laughter lies in the baring of teeth, akin to “the roar of triumph in an ancient jungle duel.” Because of these animalistic and primitive associations, Plato was not a fan of laughter. He thought that it was wrong to laugh at the misfortune of others and that hearty laughter involved a loss of control that made people appear to be less than fully human. In fact, the father of modern-day philosophy was so concerned about the potential moral damage that could be created by laughter that he advised citizens to limit their attendance at comedies and never to appear in this lowest form of the dramatic arts.

Other books

Dead Man's Gift 02 - Last Night by Simon Kernick

Sins of the Flesh by Fern Michaels

A Death-Struck Year by Lucier, Makiia

The Big Boom by Domenic Stansberry

Backlash by Lynda La Plante

Monza (Formula Men #1) by Pamela Ann

Cades Cove 01 - Cades Cove: A Novel of Terror by James, Aiden

Sheri Cobb South by Brighton Honeymoon

Spacer Clans Adventure 2: Naero's Gambit by Mason Elliott

Future Queens of England by Ryan Matthews