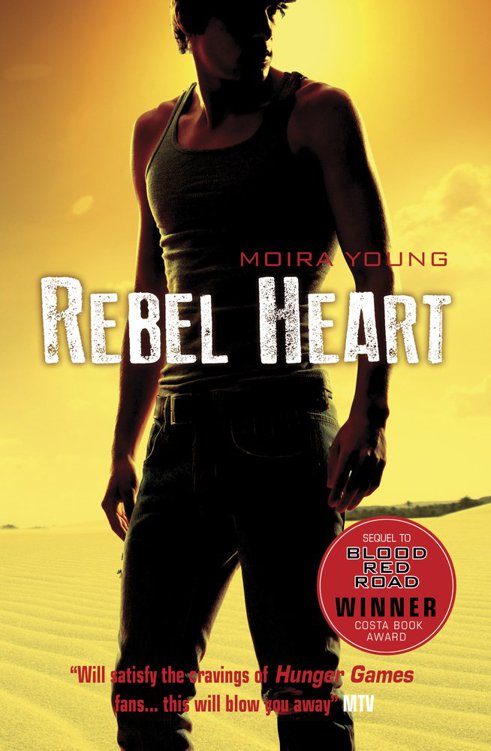

Rebel Heart

Praise for

BLOOD RED ROAD

WINNER

COSTA CHILDREN’S BOOK AWARD 2011

COVENTRY INSPIRATION BOOK AWARD 2012

BC BOOK PRIZE FOR CHILDREN’S LITERATURE 2012

RIB VALLEY BOOK AWARD 2012

SPELLBINDING BOOK AWARD 2012

SHORTLISTED

AMELIA ELIZABETH WALDEN BOOK AWARD 2012

FALKIRK RED BOOK AWARD 2012

INDEPENDENT BOOKSELLERS WEEK BOOK AWARD 2012

“A shot of pure adrenalin . . . Exuberant, exciting and charged with

emotion, its powerful, pared-down prose draws us into a world of

adventure . . . Novel of the year”

Amanda Craig, THE TIMES

“This vision of the future is hellish and frightening but if you wanted

anyone in your corner in that place, then Saba’s your girl”

TELEGRAPH

“Saba can be a tough heroine to root for, sullen and ungrateful to those

who try to help her, but fans of the

Hunger Games

’ Katniss will find in

her similar reserves of hidden good nature and ferocious fighting abilities . . .

Young has leveraged an intriguing action-romance story into a

Mad Max-

style

world that’ll leave readers both satisfied and eager for more”

BOOKLIST

“This book raises the bar when it comes to the genre . . . Not only will it

satisfy the cravings of

Hunger Games

fans, but it is – dare I say – better

than

The Hunger Games

. . . This book will blow you away . . .

a truly remarkable reading experience”

MTV

“This is a must-read, where girls rescue boys, and where the future

looms up full of hope and loss, struggles and archetypes that

give the story a timeless, classic edge”

GLOBE AND MAIL

“

Blood Red Road

has a cinematic quality that makes it white-hot

for film production… The fervour is more than warranted”

LA TIMES

“A post-apocalyptic story with the flavour of a western… Powerfully

narrated in a spare vernacular… A sure-fire transporting holiday read”

SUNDAY TIMES

MOIRA YOUNG was an actress and a singer before becoming a writer. She came to the UK from her native Canada to perform on the London stage and now lives in Bath.

BLOOD RED ROAD was her first book, published in 2011 to international acclaim. REBEL HEART is the eagerly-awaited sequel.

for my sisters

It’s late afternoon. Since morning, the trail’s been following a line of light towers. That is, the iron remains of what used to be light towers, way back in Wrecker days, time out of mind. It winds through faded, folded hills, burnt grass and prickle bush.

The flat heat of high summer beats on his head. His hat’s damp with sweat. The dust of long days coats his skin, his clothes, his boots. He tastes it when he licks his dry lips. It’s been a parched, mean road all the way. He crests a ridge, the trail dips down into a little valley and it’s suddenly, freshly green. The air is soft. Sharply sweet with the scent of the scrub pine that scatters the slopes.

Jack pulls up his horse. He breathes in. A long, deep, grateful breath. He drinks in the view. On the cleared valley floor, a small lake glints in the sun. Beside it stands a junkshack with a bark and sod roof, the rest of it cobbled together from Wrecker trash, stones, dried mud and the odd tree trunk. A man, a woman and a girl are working in the well-tended patches of cultivated land.

People. At last. Apart from the white mustang, Atlas, he hasn’t spoken to a soul for days. His aloneness was starting to weigh him down.

An there was I, he says aloud, thinkin I was th’only person on the planet.

He whistles a tune as he rides on. He calls a hello as they leave their work and come to meet him. They aren’t particularly friendly. They’ve got weary faces. Wary eyes. They’re little used to company, take little interest in the wider world and have little to say. Never mind. Just seeing them and having this awkward, mainly one-sided conversation cheers him no end.

The man’s worn out. The woman’s sick. Dying, if he’s any judge of such things. With yellowish skin, her mouth set tight against pain. The girl’s sturdy enough, fourteen or so. She stares at her boots. Silent, even when he speaks to her direct. But her plain, flat face lights with love when her brother comes running from the shack, calling her name, Nessa! Nessa!

He’s a cheerful berry of a child. A barefoot, round-eyed four-year-old called Robbie. His family gazes at him with such fond wonderment that it’s clear they can’t quite believe their good fortune. He leans against his sister’s legs, sucks his thumb energetically and sizes up Jack.

The battered, wide-brimmed hat. The silver eyes. The lean, tanned face that hasn’t seen a razor for weeks. The long, dusty coat and worn boots. The crossbow on his back, his well-stocked weapons belt – bolt shooters, longknife, bolas, slingshot.

Boo, says Jack. Robbie’s mouth drops open. His thumb falls out.

Jack growls. The boy shrieks with delight and tears off towards the lake. Nessa gives chase. The valley sings with their shouts and laughter.

They aren’t sociable people but they aren’t mean. They see to it that he and his horse are watered, washed and fed. They offer him a roof for the night, but he’s anxious to keep moving. Dusk is falling as he sets off again. They’re hard workers, early risers. They’ll be in bed as soon as he’s gone.

By his reckoning, the storm belt should be no more than three days’ travel from here. And that’s where he’s headed. The storm belt, a tavern called the Lost Cause and an old friend named Molly. He’s the bearer of bad news. The worst. The sooner he delivers it, the sooner he can turn around, retrace his steps and keep on heading west.

West. To the Big Water. Because that’s where she is. It’s where he promised to meet her.

He pulls out the stone that he wears around his neck, threaded on a leather string. It’s smooth and cool to the touch. Pale rosy pink. Shaped like a bird’s egg, a thumb’s length in size.

It’s a heartstone. It’ll lead you to your heart’s desire, so they say.

She gave it to him. He’ll head west and he’ll find her.

Saba.

He’s only just left the valley when Atlas falters. Tosses his head and whickers. There’s something up ahead. Jack doesn’t stop to think. In a moment, he’s off the trail, into the scrub pine and out of sight. From the cover of the trees, his hand over the mustang’s muzzle, he watches them pass.

It’s the Tonton. Nine black-robed men and horses. They’re escorting a couple in a buffalo-cart. The commander leads the way. Four men behind him, then the cart, followed by three men on horseback. The last man, the ninth, is driving a wagon with an empty prison cage.

He studies them carefully. He knows the Tonton well. They’re rough and dirty and casually violent. A loose collection of amoral thugs who swill around the power. Only loyal to each other, only answering to a master if and when it suits them. To a man, they’re ruled by self-interest. But these ones seem different. Everything about them is clean and shiny and polished and ordered. They’re well armed. They look disciplined. Purposeful.

And that makes him uneasy. It means that the enemy have changed their game.

He checks out the couple in the cart. They’re young, strong, healthy looking. A boy and a girl, no more than sixteen or seventeen. They sit close together on the bench seat. The boy’s driving. He holds the reins in one hand. His other arm circles the girl’s waist. But there’s a gap between their bodies. They sit stiffly upright. They aren’t comfortable, that’s for sure. It’s as if they hardly know each other.

They stare straight ahead, their chins held high. They look determined. Proud, even. Obviously not prisoners of the Tonton.

The cart’s neatly packed with furniture, bedding and tools. All you’d need to set up house.

As they rattle by, the girl turns her head sharply. She stares into the trees. Almost like she senses that somebody’s there. It’s dusk and he knows he’s well hidden, but he shrinks back anyway. She keeps on looking until they’ve gone past the woods. No one – not the Tonton, not the boy sitting beside her – seems to notice.

Jack gets a clear view of her forehead. The boy’s too. They’ve been branded. And not long ago. The circle, quartered, in the middle of their foreheads looks raw and sore.

They’re headed into the valley. Towards the homestead. With an empty prison wagon.

Now he’s more than uneasy. He’s worried.

Keeping to the trees, leading his horse, he turns around and follows them.

From the wood at the top of the valley, as darkness begins to fall, he has a clear view of the homestead he’s just left. The Tonton are already entering the shack.

He has to stop his feet from moving towards them. Halt his hand as it reaches for his bow. Because the survivor in him knows that this is a done deal. Whatever’s about to happen, he can’t stop it.

But he can bear witness. He will bear witness. With clenched fists and a rising rage, he watches what happens below.

By now they’ve roused the family from their beds. The weary man and woman, their children, Nessa and Robbie. Flushed them out at the point of a firestick. They huddle together in the fading light while the Tonton commander makes a short speech. Probably telling them what’s going to happen and why. Words to frighten and confuse people already too frightened and confused to properly listen.

Jack wonders why he bothers. It must be procedure.

The young branded couple wait in the cart, ready to move into their new home. A land grab. A resettlement party. That’s what this is about.

Everybody looks small from up here. Doll-sized. He can’t hear what’s said, not the words. But he can hear the alarm in the raised voices of the family. The girl, Nessa, falls to her knees. Pleading with them, holding her brother tight. One of them takes Robbie while two others grab her by the arms. They move towards the prison cart. She struggles, yelling, looking back at her parents.

They shoot them at the same time. Husband and wife. A bolt through the forehead and their bodies crumple to the ground. Nessa screams. And this time, Jack does hear. Run, Robbie! she screams. Run!

The little boy kicks and wriggles in the Tonton’s arms. He bites his hand. The man cries out and drops him. Robbie’s free. He runs through the fields, as fast as he can, while his sister yells to go faster. But it’s summer and the crops are high and he’s only four years old.

The commander shouts orders. One man starts after the little boy. Too late. The eager new settler is out of the wagon. Aiming his firestick. He shoots. Robbie drops in his tracks. The wheatgrass folds around him.

The commander’s lost control of the situation. It should have gone smoothly. But it’s chaos. As he and the settler yell blame at each other, Nessa begins to scream. Her high-pitched wail of grief and rage shivers Jack’s skin.

Her shirt has been torn. The men laugh as she tries to cover herself, weeping, screaming, lashing out. They pin her hands behind her. One of them touches her roughly.

The commander sees it. He moves fast. He shoots his man through the head.

Somehow, in all the confusion, Nessa gets hold of a bolt shooter. She shoves it in her mouth and pulls the trigger.

Jack turns away. He leans his head against the white horse’s neck, drawing in deep breaths. Atlas shifts uneasily.

What a mess. A botched job. They were obviously supposed to take Nessa and Robbie, young and healthy, and kill the sickly parents. Instead, all dead.

The Tonton have changed their game all right. He’d heard rumours of land grabs and resettlement months ago. But not this far west, never this far west. They’re rolling over the land like the plague.

If this is Tonton territory, then so is the storm belt. And that means Molly’s in danger.

Now he’s more than worried. He’s afraid.

Jack leaves the trail. It isn’t safe.

He and Atlas travel east along unknown roads. The going’s hard and unfriendly. Dark, stony ways, never warmed by the sun and seldom used. He spots the odd traveller in the distance – a moving dot in the landscape – but they must be as keen-eyed and eager as he to pass without notice because that’s as close as anybody ever gets. He hurries, resting for an hour here, two hours there. He has plenty of time to think about what he saw.

The Tonton. Most recently, the private army of Vicar Pinch: madman, drug lord and self-styled King of the World. Now dead.

They defeated the Tonton at Pine Top Hill. He and Saba and Ike, with the help of Maev, her Free Hawk girl warriors and their road raider allies. And Saba killed Vicar Pinch. But they didn’t wipe out the Tonton. They didn’t kill every last one. Even if they had, he’s lived long enough, he’s seen enough to know that you can’t kill all the badness in the world. You cut it down in front of you only to find that it’s standing right behind you.